Astro Physics AP1200GTO

Astro Physics are a phenomenon.

The reason, I suspect, is that boss Roland Christen isn’t really in it for the

money. If he was, he wouldn’t have decade-plus waiting lists on his scopes .

However, I don’t know if the reputation

for excellence in optics is deserved, because I have never even seen one of

their scopes, let alone seen through

one. It’s a truly weird situation for a consumer product. Their ordinary scopes

have limited runs and so become instant collectors’ items. Their premium

instruments, made in minute numbers that AP don’t divulge, are offered to

favoured customers and are so rare that they fetch insane prices used: the ten

inch Maksutovs they made a few years back are now worth the sort of money that

would buy a cheap holiday home.

If I sound bitter, it’s because I

am. Not a few AP telescopes get put in safes like gold bars; never used, never

even unpacked. That’s not AP’s fault, but is a bit ridiculous all the same.

Up til recently (and from what I

hear in future), the mounts were a bit like that too. Then a few years ago,

perhaps with the recession biting, maybe because they had upped production, it

became possible to get the mounts at short notice. And they weren’t even

expensive: less than the equivalent Takahashi.

So I bought an AP1200 – the

biggest of the range at that time (AP now make a much bigger mount as well -

the mammoth “El Capitan”).

Design and

Build

I have an AP extension tube, just

a piece of aluminium tubing really, with male and female 2-inch fittings. But

that humble extension tube is way over engineered and contains

precision-engineered knife-edge baffles, and perfect super-matte blacking like

the tube for a premium APO. It shows an obsessive attention to detail that goes

way beyond the profit motive. AP could sell an extension tube like everyone

else’s for the same money. But no, they had to make the best possible extension

tube. The AP1200 is a bit like that.

AP extension

tube: more knife edge baffles than some APOs.

In essence the AP1200 is just a

big German equatorial mounting with a built-in GOTO system and a clever way of

splitting the RA axis from the Declination axis on a dovetail. Like the

extension tube, the specialness of the AP1200 is in the detail.

Every component on the AP1200 is

made from the finest materials and carefully designed for purpose. This is hard

to explain, you have to experience it, but I’ll try...

There are no ferrous metals in

the AP1200, so it won’t rust in your observatory. By comparison I could tell

you an eye-watering tale of a used Takahashi EM500 that was for sale and was

breaking out in rust all over, like an old banger.

All the electrical connections on

the AP1200 are mil-spec for ruggedness and the electronics are mil-spec as

well, so the built-in computer will still work at -40 (whereas your PC...

err... won’t).

Every knob is custom milled from

alloy; there is no plastic. Those annodised knobs are works of art, specially

sculptured for ease of use in the cold and dark.

The motor housings are

constructed from CNC’d parts held together by tiny stainless allen screws.

Every knob also contains a hex

socket so you can tighten it with an Allen key (a set of premium Allen keys is

supplied with the mount).

The mount is driven by micro-controlled

servo motors - the best Swiss ones.

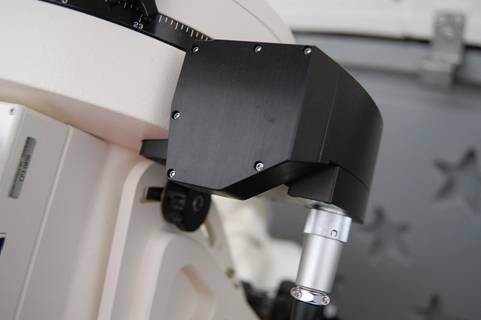

RA servo

motor housing detail. Note the mil-spec connector and tiny stainless Allen

bolts.

The five RA bearings are huge

(9.5” diameter) and so finely balanced that with no load the RA axis will slowly

turn on its own, millimetre by millimetre, due to the slightly bottom-heavy

Dec’ casting; yet try to turn it by hand and it takes surprising force to move

it at all.

The RA gear is ten inches in

diameter and was made by the same company that made gears for those Mars rovers

that (as I write) are still working six years after they should have failed.

Any gears that fail the five arcsecs benchmark are scrapped.

The knob for adjusting the

altitude of the RA axis has a little screw in bar (beautifully milled from

stainless) to help turn it. You can remove the bar after setup to avoid

inadvertent changes to your alignment.

The covers for the polar

alignment ports, front and rear, are some of the most finely machined items

I’ve seen, where everyone else uses plastic plugs.

Make no mistake, the engineering

on the AP1200 is absolutely superb and uncompromising. The only other time

you’ll see engineering at this level is for defence applications (no surprise

that’s Roland’s background).

The result of all that over-engineering

is that the AP1200 is rated for a relatively massive load of 65 Kg. I can’t

comment on that, but it certainly chucks my 7 inch refractor and tube weights

(35 kg) around as if it wasn’t there.

All the other specs reflect the

AP1200s design brief as a premium imaging mount for big scopes, including the

high maximum slewing speed of 1200x siderial (hence the name). Incidentally,

the “GTO” part of the name apparently comes from Roland Christen’s other

passion: Muscle Cars.

Accessories

AP sell a comprehensive range of

accessories for the AP1200 that you may

need: CNC plates, dovetail shoes, dovetail bars and trays. What you definitely will need however, are some

counterweights, a pier and a pier adaptor.

The optional counterweights are

stainless, expensive and come in various sizes, the biggest of which weigh 18

lbs each. The weights are provided with brass sleeves and brass locking pins

that are softer than the shaft and so don’t mark it (more of that attention to

detail).

The standard AP Portable Pier is

held together only by three tensioning bars (so there are no bolts to unscrew).

Broken down, the legs come off to leave the pier in small easily hefted chunks:

it’s simple but it works. A fancier ATS-made pier is available through AP, but not

sure I see the point of this (except it looks vaguely like a rocket).

To fit the mount onto the pier

(any pier) an adapter plate is required. The mount fixes to the plate by four

knobs that are loosened to align the AP1200 in azimuth, so the plate effectively

acts as a bearing surface for the mount to move on.

In Use

Setup

The AP 1200 came in several large

cardboard boxes, protected by Ethafoam. Everything was carefully labelled, even

the screws and bolts were in special labelled packets to avoid confusion (Ikea

take note). So putting the mount together was a doddle.

Declination

and RA axes as they came fresh from Astro Physics. You can see the way the

mount splits along a dovetail.

Despite being a heavy duty mount,

the AP1200 is one-man portable because it comes apart in two big sections along

a circular dovetail joint just in front of the RA gear housing. The dovetail is

a clever feature, because it requires no tools to set up: just fit it together

and tighten two knobs. The two halves of the mount, RA and Dec’, weigh 22.7 kg

and 14.1 kg respectively. The only remaining component is the long

counterweight shaft which weighs a whopping 6.4 kg on its own and attaches via

a huge thread (shorter shafts and even extensions are available).

So setup essentially just

involves screwing the adapter plate to the pier top, plonking on the RA

section, attaching the Dec axis via the dovetail and screwing in the

counterweight shaft. After that, it only remains to connect up the electrical

and install the scope and counterweights.

Unlike, say, a big Takahashi

mount, all the electronics to the AP1200 are external. The control unit is a

small (10cm x 10cm x 2cm) box piggybacked on top of the RA axis and held on by

just a couple of set screws. The control box connects to the motors via a

Y-shaped cable with military type bayonet connectors. The handset then connects

to the control box and that’s it.

Control box

is separate from the mount, all cabling is external.

(I originally thought that the

external wiring was an inferior aspect of the big AP, but it is in fact a well

thought out feature. If you want to replace or repair or upgrade the control

box, doing so is quick and trivial and future-proof. The mount itself is simple,

rugged and sealed, containing no electronics at all).

The top of the Declination axis

is a wide plate with various threads. You can attach any one of various AP

plates to hold big scopes firmly and orthogonally with centring screws, or

various dovetail plates for more flexible connections. I would strongly

recommend the former, for reasons that I’ll come back to.

Alignment

I’m going to spend some time

talking about alignment. If you intend buying an AP1200, you should read this,

if not you can safely skip it!

If the AP1200 is Zen-simple in

the setup, alignment is where it starts to show its “Fools need not apply”

approach to operations.

Astro Physics don’t supply a

polar scope with the AP1200 (though you can buy one as an accessory). They

point out that by using the alignment routines in the handset your telescope

becomes a super accurate polar-scope... in theory.

The handset has several alignment

functions that use various stars or the pole star to iteratively hone the RA

alignment. These routines are simple in theory, but they can be extremely

frustrating in practice, unless you’ve some experience and have met the

pre-requisites.

The daylight setup routine is a

God-send that saved my sanity when getting started with aligning. You get the

mount and scope roughly pointed north, then level the OTA and counterweight

shaft with a spirit level. This is park position one of three. Then you re-park

in position two and again level the OTA with a spirit level by adjusting the

big knurled knob that changes the RA angle. That gives good rough altitude

alignment, fine for general visual use. I then used a laser pointer resting on

the casting to get an approximate azimuth alignment on Polaris (looking through

the polar finder tunnel is another easy option).

If you want better alignment than

that, things get tough. The problem is a thing called “orthogonality”, which

means everything has to be perfectly square and free from play: OTA, rings,

focuser, plate, dovetail, diagonal and optics. If your orthogonality isn’t

spot-on, the alignment routines just don’t work. Read that again – you’ll thank me when you try this at home...

when it’s late... and dark... and cold... and you’re tired... and you’ve been at

it half the night already.

Now if you’re getting bored, know

this: your scope(s) probably won’t be orthogonal enough to align an AP1200;

mine weren’t. I tried (over the course of many frustrating hours)

various high end refractors attached to a Losmandy plate and APs own dovetail

before realising that a dovetail just isn’t accurate enough for the job. What’s

more, many fine scopes (like Takahashi’s, for example) won’t work because there

is too much play in the focuser and the holes for mounting the tube rings.

What is required is a scope with

a CNC tube and rings that directly fit onto one of APs own plates, because then

everything aligns perfectly with centring screws that permit no play. After that, all you need is a focuser with

zero image shift and a reticle eyepiece!

AP’s own

plate with rings directly attached via recessed self-centring screws.

I couldn’t use the TMB 175 for

alignment, even though it’s all CNC, because it’s just too long to allow the

mount to slew it around uninterrupted (as it has to when following the

alignment routines). The problem comes if you have to stop the slewing during

the routine (if there’s a risk of hitting the dome, for example): do that and

you have to start from the spirit level again. So I ended up buying a Skywatcher

ED120 just to align the mount. The ED120 is all CNC and the rings (oddly

enough, I thought) have AP-pattern mounting holes.

The

Skywatcher ED120 makes a great alignment scope: CNC tube and focuser, with CNC

rings that bolt straight on the AP plate.

Of the alignment routines, the

one I found best was the one that simulates drift alignment. This works by

selecting a star near the meridian and hitting GOTO. You then set the scope

precisely onto that star by loosening the RA and Dec’ clamps and moving the

scope manually. Having done that, you tighten the clamps again and trick the

mount by moving its understanding of the Meridian a couple of hours (there’s a

menu option to do this). Now if you hit GOTO again, the mount swaps the

telescope onto the other side of the mount, but hopefully pointing near the

same star. You can now adjust the actual mount alignment, in the way you adjust

most German equatorials, by turning the altitude and azimuth knobs (it’s

probably best to loosen the locknuts first, tighten them again afterwards). Do

this several times and you gradually get better and better alignment (or worse

and worse alignment if your orthogonality is out).

All in all I tried for several

nights and many hours before getting the hang of aligning the AP1200 and a

frustrating business it was. The manual has muddy boot marks all over it to

prove that by the end I was so frayed I didn’t even notice treading on it in

the dark. The problem is neither the mount, nor the manual (which is well

written and clear, unlike that for a Tak’ mount). It simply requires

experience, practice, accuracy and that all important über-orthogonality to get

the process right.

Tellingly, the routine Roland

uses and recommends is proper drift alignment that requires a CCD camera with a

“track and accumulate” mode (which I don’t have).

When aligning the AP1200 I recommend purchase

of a polar scope, or lots of patience (or Valium).

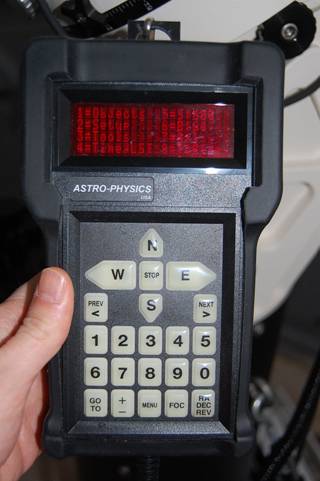

Handset

The handset is a built-in GOTO computer;

no external PC is required. It is ruggedly made and has a rubber shroud like a

big iPod case. As I said before it is rated down to -40 °C and I have

personally used it down to -15 without problems. The handset has large, chunky

buttons (good for cold hands), all of which are lit when the mount is powered

and have built-in luminescence for when it’s not. The display is an

old-fashioned four-line vacuum display with variable brightness. Why? Because

obviously (says Roland, irritably) a

graphics LCD would fail under extreme conditions.

The handset

showing the root menus. Options 5 & 6 are the GOTO and manual slewing

speeds

(set to 600x

and 64x sidereal, respectively).

The handset is not as user friendly

on first acquaintance as some, but (of course) it works very well indeed once

you’re used to it. The interface is simple, with various selectable numbered

menu items at each level (you use the “Menu” key to go back up a level). In

some cases repeated selection toggles through various possible values (e.g.

selecting “6” toggles through all the possible manual slewing speeds from 1200

to 0.25).

GOTO options include a high level

“Objects” menu (option “1” above) that contains a huge array of sub-menus to

select what you want to look at in various ways. Quick menus are provided for

the Solar System and Stars, or you can choose a “What’s Up Now” random tour

option or a very handy feature that tells you what objects are available in the

constellation you’re looking at (or any other).

Other menus do things like:

·

Park

the mount (three different positions).

·

Change

the GOTO slewing speed between 600x and 1200x.

·

Changing

the tracking speed from Siderial to Lunar or Solar (option “8” in the picture

above).

·

Look

up or set the time and location (various locations can be stored and selected).

·

Use

a timer for photo exposures – very handy, it beeps when you’re done.

·

Change

the Meridian position to fool the mount into staying on one side or the other –

incredibly handy when imaging or if you are tight for space and you don’t want

the scope to swap sides.

·

Set

movement limits to take into account your pier or tripod, or your horizon.

·

Various

possibilities for recording or using PEC (Periodic Error Correction) that I haven’t

tried because I can’t take exposures long enough to need it with my DSLR.

The key to using the handset is to understand

that it is designed with rapid operation as paramount (no irony intended!). Ease of learning is sacrificed somewhat to

ultimate speed and efficiency. But that doesn’t mean that it’s unclear or

illogical, it’s not, just don’t expect too much excess friendliness (e.g. the

Solar System menu is simply labelled “Sol” for brevity). Think “UNIX” not

“Windows”.

There are none of those infuriating

Meade-style warning messages, unless you GOTO the Sun, or something near it.

The handset can be configured for a permanent location so that it goes straight

to the main menu on startup. Boot-up is a

fraction of a second, so you can be going to your first object three key clicks

and a few seconds from powering up the mount.

The only real gotcha I found is

that hitting the “next >” key twice re-syncs the mount and it’s right next

to the big “E” slewing button! Make that mistake whilst also using the meridian

delay and it’s back to the spirit level – not a good experience at 2:00 a.m.

Pointing and Tracking

Once you’ve aligned it and

learned to use it, the AP1200 is a fantastic tool for visual or imaging use. Slewing

is very quick and precise, objects are held stably and accurately enough for

imaging at very high magnification (for example when using a webcam).

Vibrations are very efficiently damped, even using the portable pier and a big

OTA like the TMB 175. The vast range of slewing speeds is very useful when

doing imaging. The tracking is almost inaudible and the slewing very quiet.

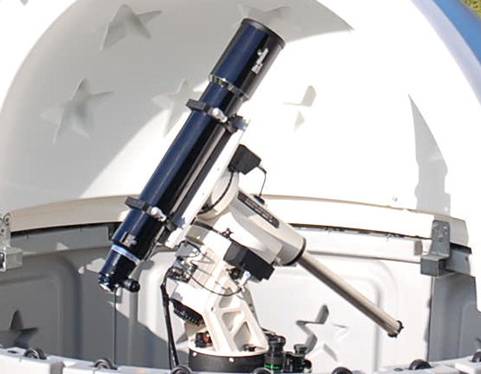

The AP1200

with TMB175 mounted. This is actually a light load for the mount, with just two

counterweights in use.

One of many good things about

having a mount capable of such big loads is that you can pile extra stuff on it

without worry. I have cobbled up a tube counterweight for the TMB 175 (that

lens is very heavy) which weighs about 10kg – the AP1200 takes the extra without

trouble and I’ve plenty more capacity to spare for guide scope, camera etc.

I found GOTO pointing accuracy

good enough to put target objects reliably in a ~ 1 ° field anywhere in the

sky. AP claim pointing accuracy to 1 minute, but I have never achieved this,

probably because my alignment is still not quite perfect. Even so, this means

you can discard your finder unless your scope has a focal length of well over

two metres.

In practice, it is very easy to

just GOTO from one object to the next, imaging in quick succession without

changing focus. Another advantage is the ability to focus accurately on a

bright star and then GOTO a much fainter object and image it directly.

I have used the AP1200 in very

cold conditions (very damp, foggy ones too) and it has never behaved any

differently from when the conditions are ideal.

Control Box Problem

I did have a problem with my

AP1200 very early in our relationship. The mount just stopped tracking one day

after just a few hours of overall use. It eventually turned out to be a dry

soldered joint in the control box (AP use lead free solder these days), but the

box had to be returned to AP to fix it (for free, and I only had to pay

shipping one way). I should point out that AP arranged a conference call with

the engineers very early on and were very efficient, friendly and helpful in

diagnosing the problem.

Summary

I suspect I know Roland Christen

from his brain child, the AP1200. If I’m right, Roland is clever,

uncompromising, perfectionist to the point of mania and probably doesn’t suffer

fools gladly. I’m glad Roland is like that, because if he weren’t the AP1200

probably wouldn’t exist. For the AP1200 is a superb and obsessively refined

product that exhibits exquisite design and workmanship.

I can’t pinpoint any real

weaknesses in the AP1200, apart from that dry soldered joint and the odd

suspected software glitch. Once aligned it does exactly what it is supposed to

do, does it reliably and swiftly and quietly and is very easy to use

efficiently. The design is very, very well thought through. Personally, now

that I’m used to it, I wouldn’t be

willing to swap the quick-start brevity of the handset for a more user-friendly

interface.

However, excellent though it is, the AP1200

is emphatically not a mount for a beginner. Don’t buy this before you have some

experience in astronomy. Saying that

may sound dismissive, but I mean it sincerely: the AP1200 could easily put a

novice off this hobby, because it requires considerable skill, patience and

experience to align it properly. It gave me enough trouble before I learned to

do it and I’ve had many mounts before, know my Meridian from my Zenith and have

worked with computers for many years. When I put this to a major seller of AP

mounts in Europe, he laughed and told me he reckons there are many AP1200s out

there whose owners can’t align them; sad if true.

If you can get your head around the alignment

routines and the initially rather terse and unfriendly computer interface, the AP1200

is a peerless tool for both high-power observing and critical imaging.

The AP1200 is very highly

recommended, but absolutely not for novices.