March 9th

2025: Politics and Reviewing

I’m currently reviewing two Russian refractor objectives – LZOS’s 130/1200 and LOMO’s 80/480.

But Russia. I’ve spent quite a lot of time in Russia and I love the place, the culture too. I even speak a bit of Russian. But the Putin regime is abhorrent to me: Ukraine, but also Salisbury. At the time I viewed the latter as an act of war; I recently discovered the head of MI6 at the time thoughts so too.

Should this affect my POV on Russian products? By analogy, many specialist journalists and reviewers have turned mildly or extremely negative on Tesla and SpaceX lately: not just Musk, not just the companies, but the products too. Check out Clean Technica’s or Electrek’s Tesla coverage for egregious examples.

I’m dismayed and angry over Trump’s (and Musk’s) treatment of Zelensky and apparent support for Putin, but I think this kind of journalistic bias is unacceptable and unprofessional; risible actually. Their job (and mine here) is to provide an impartial opinion of the product. And honestly, how many products do we all consume made by PRC-owned companies (in terms of cars, including MG)? Don’t look too closely at the politics of the Porsche or Swarovski families, either.

So I will continue to give an honest opinion on products based on their merits, not on their perceived political affiliations. At most, I’ll note political concerns and move on.

Those Russian lenses are both top-drawer, BTW. Reviews soon.

December

13th 2024: Takahashi’s Multi Flattener

Takahashi

Multi Flattener and CA Ring 65 on the back of an FC-60 in place of the

1.25” eyepiece holder.

My previous post about Tak’s new imaging refractors and their super new ‘FU’ reducers (!) got me thinking. I mean a 0.65x reducer is pretty impressive, but do you really need such a fast scope (F4.0 in the case of the FCT-65)?

If you don’t, then Takahashi have a (much) cheaper option available: their 1.04x FC/FS Multi Flattener which offers a 44mm (full frame) on recent models or a 40mm image circle on older ones.

Unlike the old dedicated flatteners for scopes like the FS-60, the Multi Flattener works across most small Tak refractors, past and present. All you need to swap to a different scope is an adapter ring that Tak’ call a ‘Multi CA Ring’ that gets the spacing right.

In theory you can get a Multi CA Ring for old models from the FC-60 (above) through the FS-152, as well as most recent small refractors like the FC-76 and FC-100. It’s great that Tak’ is still thinking about the owners of 1980s scopes!

The CA ring threads onto the back of the flattener, with the only gotcha that it terminates in an M52 male thread (not the usual M42 T thread or M48 Wide-T). Tak’ want you to buy one of their expensive M52 camera adapters, but if you have a Baader or similar wide-T already, just get a cheap M48-M52 adapter instead.

I plan on testing the Multi Flattener across a range of Tak’s scopes.

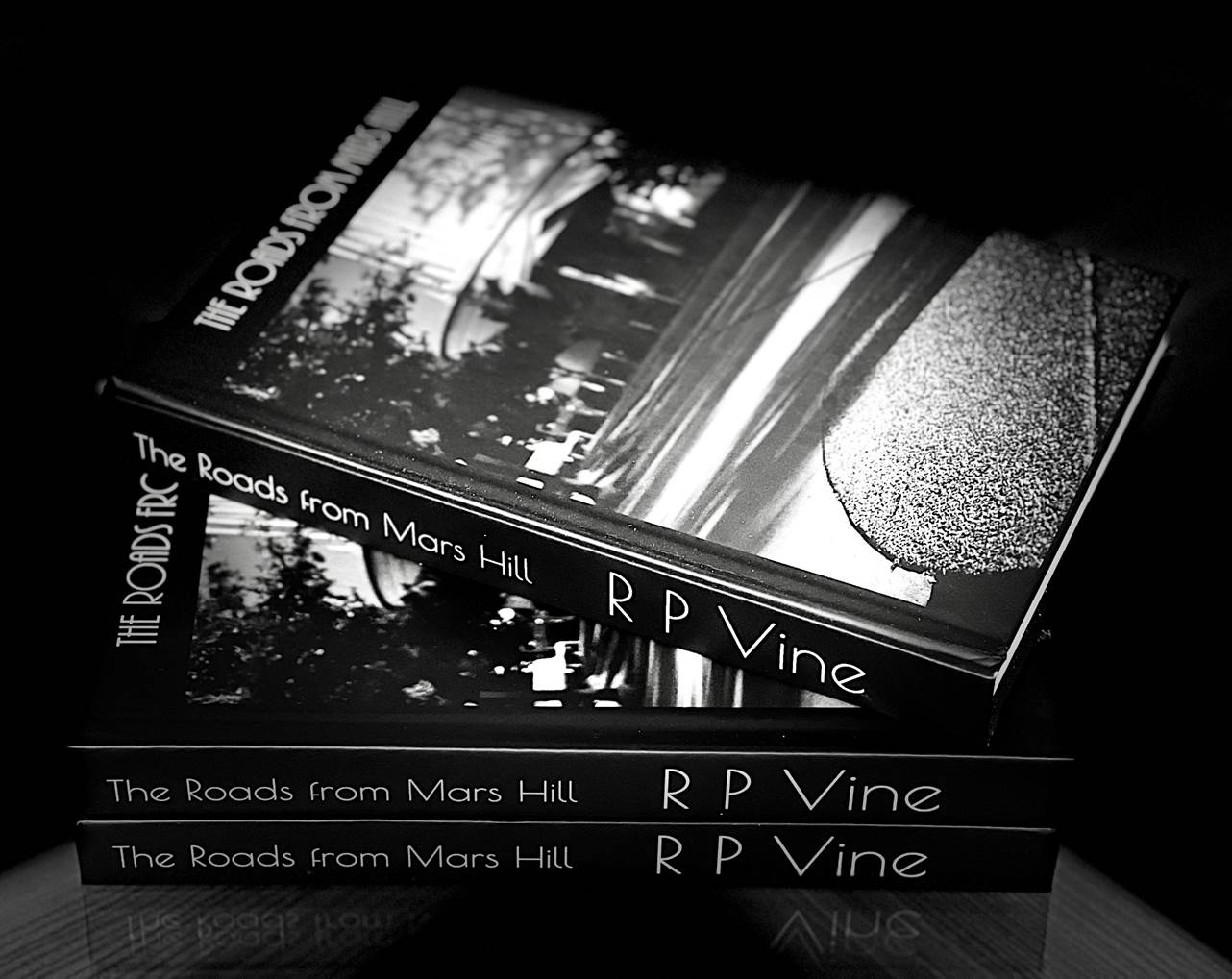

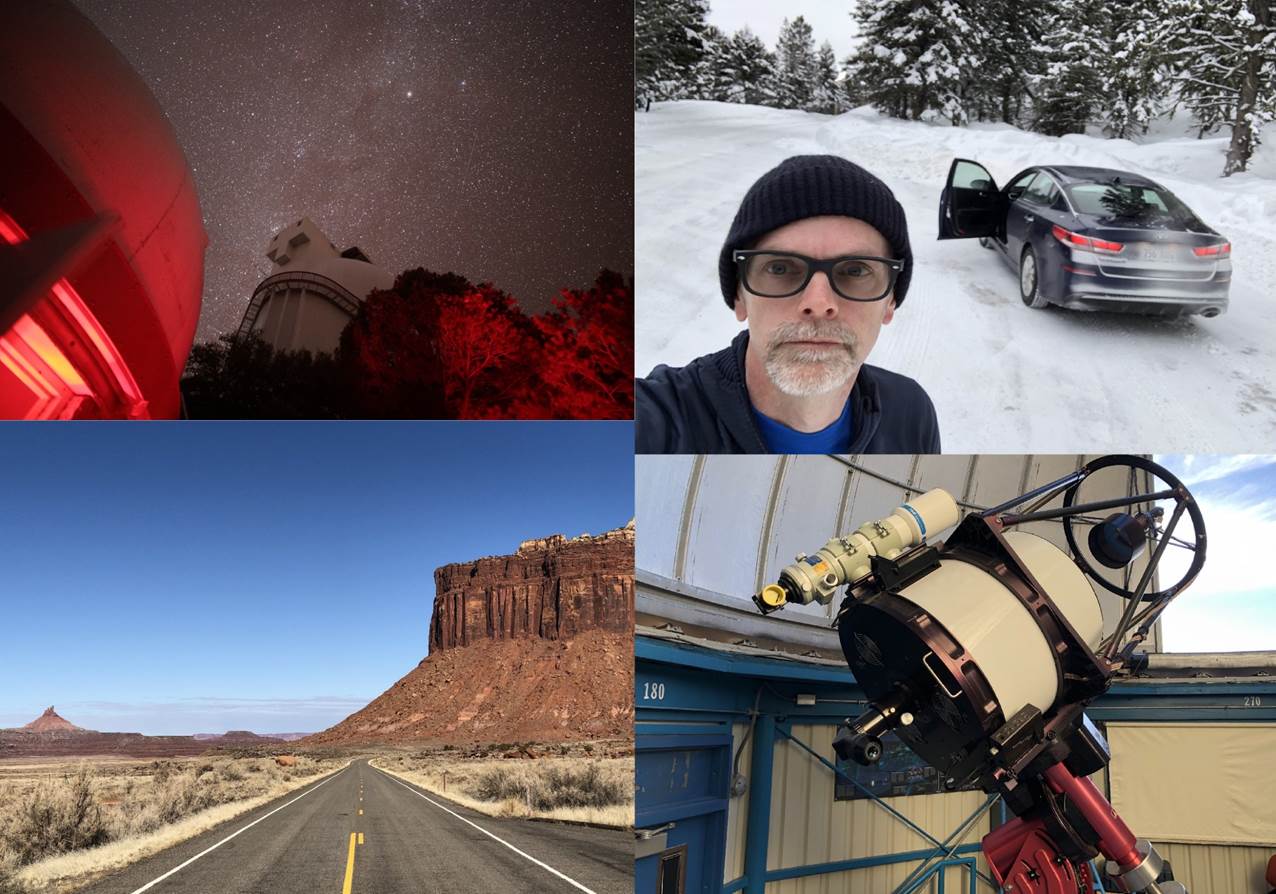

Pinned:

The Roads From Mars Hill 2nd Edition - Now Available in

Hard/Softcover!

(Click the

image to check it out on Amazon)

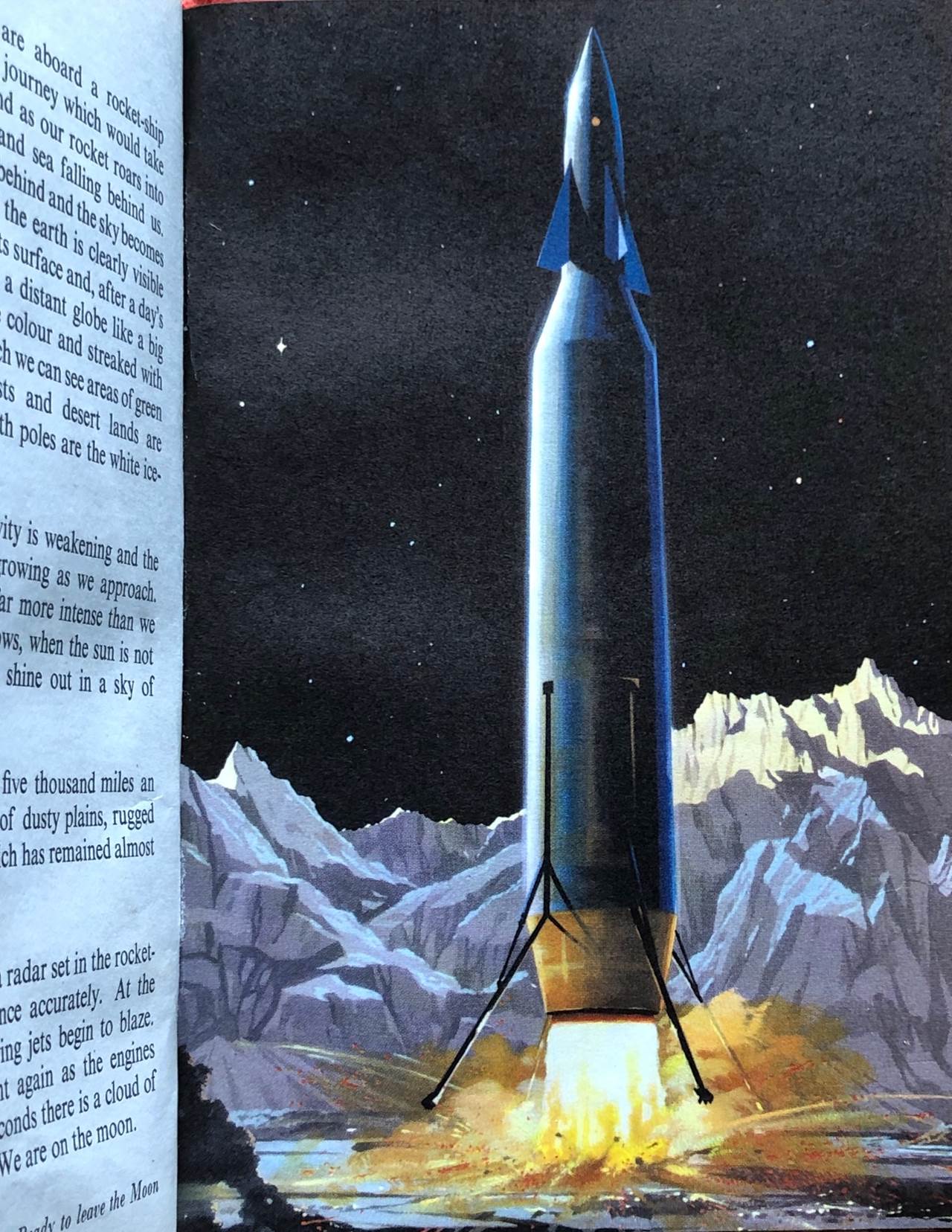

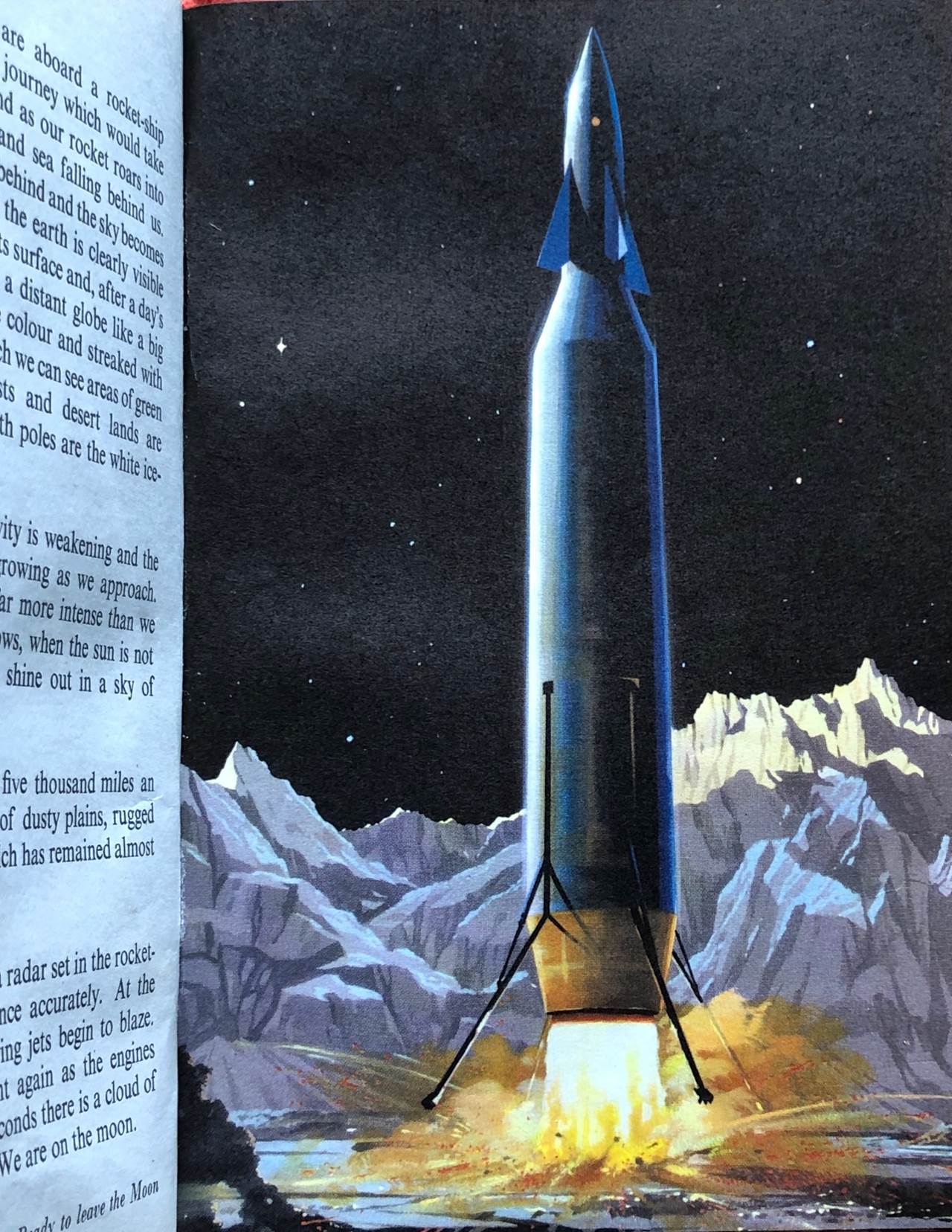

My latest book The Roads From Mars Hill is an epic desert road trip in search of Percival Lowell and his extraordinary legacy – from giant Edwardian telescopes to nuclear Mars rockets, UFOs and SpaceX. If you like my travel section, I think you’ll like it!

Now a completely revised 2nd edition with lots of new astro’ content and available as a paperback or – my personal favourite – this handsome hardcover (as well as on Kindle).

Click the image above for an Amazon link, then download

the Kindle sample and see what you think!

December

2nd 2024: New Takahashi Models

A couple of months back, a brace of new Takahashis – the FCT-65D, FC-76DP and FS-60CP and– appeared on their website. Now that they’ve just launched three fancy new reducers to go with, I thought I’d take a quick look at them here.

All three are small fluorite apochromats (no surprise) and

all three share the same unusual look, with a fatter 95mm tube section at the

back connected to a section of 80mm tube holding the objective. Two of those

objectives are from existing scopes – the 60mm F5.9 fluorite doublet from

the FS-60 and the 76mm F7.5 fluorite doublet from the FS-76D. The third

objective is new – a 65mm F6.2 fluorite triplet.

The reason for the wider rear tube is to hold the larger, more imaging-friendly focuser from the FC-100DF instead of the smaller one originally from the FS-60.

The larger focuser should vignette less on large sensors, cope with heavy cameras better. All three models support the cheap-but-good 1.04x flattener, but Tak’ have developed a new, dedicated high-end ‘FU’ reducer for each scope.

Whether the reducers are so named cos they really are an FU to lesser reducers I don’t know, but they are fluorite quadruplets giving an impressive 0.65x (!) reduction in focal length, so maybe. Performance of the reducers looks outstanding, with very wide and well-corrected fields, but at a high price.

The basic scopes are competitively priced … in Japan. Not so much in Europe. Still, you get a 2” eyepiece holder and a camera angle adjuster thrown in for free. The 95mm tube section should mean you can use any old 95mm Tak’ clamshell if you want to avoid the nice but expensive CNC rings.

I’m hoping to try at least one of them and review

it. I’ll keep you posted.

October

25th 2024: New Content Incoming!

I haven’t posted much new stuff on Scope Views this year. Wish I could tell you that’s cos I’ve been chilling on a beach somewhere (especially this one with an observatory)! In fact, I’ve been updating my gothic YA novel Fugue – you can check it out in the ‘Other Writing’ link off the website if you’re curious – and writing a sequel.

The good news is I’m back to writing lots of new content for Scope Views, with a bunch of new reviews coming and updates to existing ones too. Subscribe on social media or check the website for updates.

April 11th

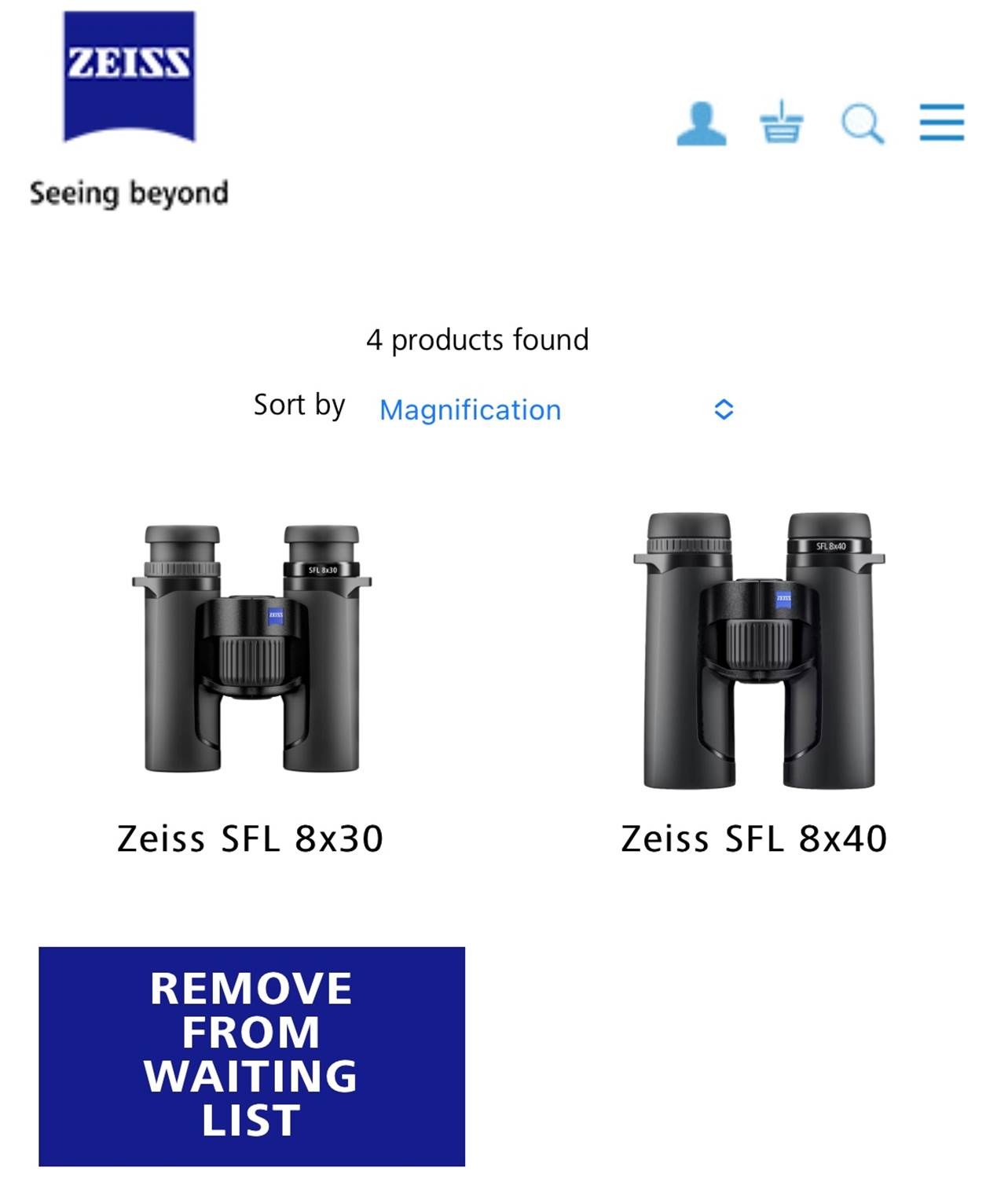

2024: Zeiss Discontinues ‘Try Zeiss’

Very

sadly IMO, Zeiss have discontinued their Try Zeiss service which allowed me to

get hold of and review new Zeiss products. Why is this a problem? Most Scope

Views readers seem to imagine I receive press loaners from Zeiss, Swarovski,

Leica, Nikon etc. I wish! But it’s just not true.

In

reality, the only loaners I get are from friends (thanks guys!) and kind

readers like you. So when a new and tasty piece of gear comes out for review I

have two choices: buy it, or go on the waitlist for a loaner if available. The

former gets expensive fast. The latter can be frustrating.

In fact getting hold of gear to review is usually the bottleneck to more

Scope Views content. If you know of any optics companies who might be willing

to loan me some kit, please let me (and/or them) know!

March 1st

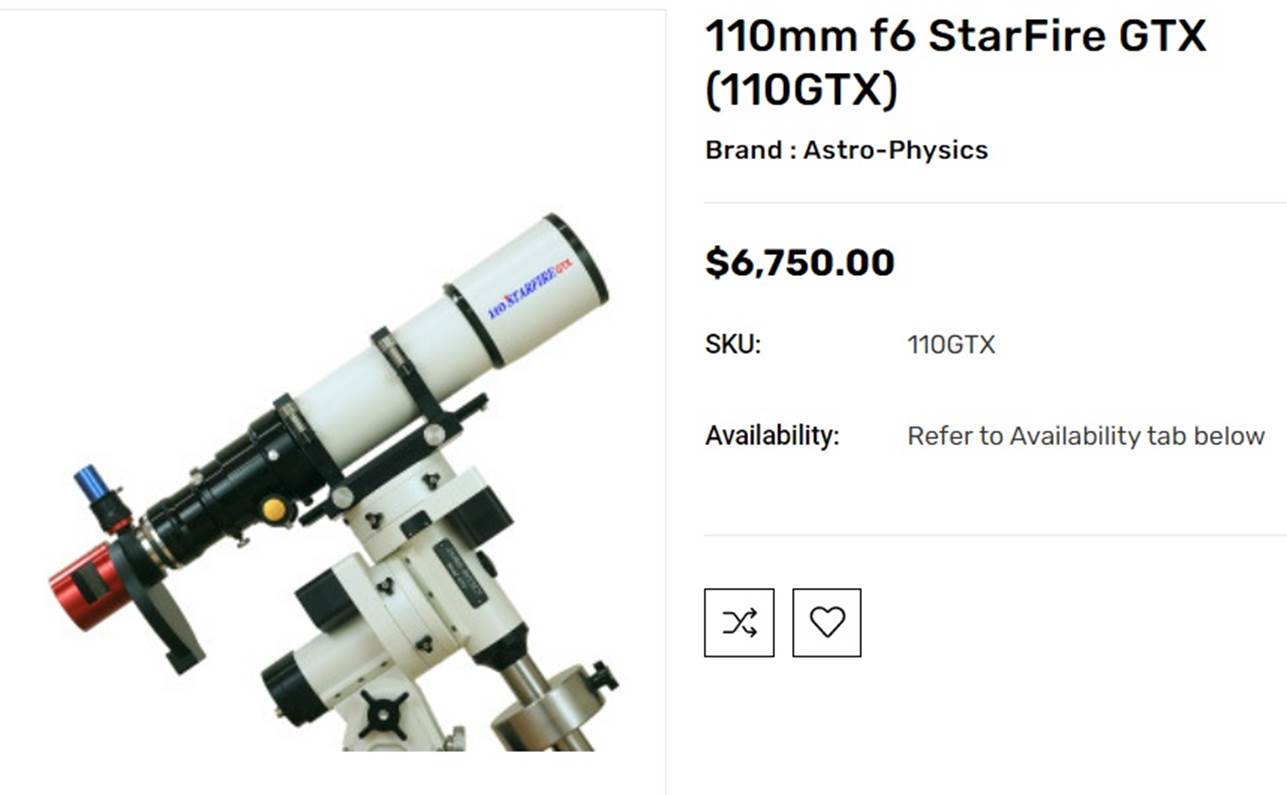

2023: Astro Physics 110 GTX Update

Last

November I blogged about Astro Physics’ new refractor, the 110 GTX: a

super-compact photo visual 110mm F6 with superb correction and a massive

in-house focuser to take a heavy imaging rig.

The

110 GTX is effectively the replacement – 20 years on – of one of my

all time favourites, the Traveler, so I was pretty

excited about it.

Yesterday,

AP finally released the dates for the draw and I spent the evening (and unfortunately

some of the night) fretting over whether I was going to try and get one. The

reason for my angst? The price…

Last

November I estimated $5000-6000 including case and rings. I based that estimate

on AP’s other current models: the 92mm Stowaway ($3750) and the 130 GTX ($7490).

I

was wrong. The 110 GTX is $6750 including the case but without the rings and

plate that I got thrown in with the Stowaway. So why is the 110 GTX so

close to the 130 GTX in price despite being slightly closer to the Stowaway in

aperture? Some thoughts…

“Why?

Because they can…” Opined a friend. But then AP could doubtless

have charged (a lot) more for the Stowaway, but didn’t. There has been

talk of delays, so perhaps the objective or the focuser have proved more

challenging or more expensive to produce than expected?

To

achieve a 110mm F6 foil-spaced triplet (i.e. avoiding big air gaps for

ruggedness), with 90% Strehl across the whole visible spectrum, AP are using

the very latest ED glass – FPL55 in place of FPL53. Is it possible that

they’re having to reject a lot of blanks? Roland has noted that Ohara

don’t guarantee internal

homogeneity beyond a basic level, writing:

“It

can be so bad that the entire batch of 50, 100, 250 or 500 blanks that were

delivered show 2 to 5 waves of astigmatism and must be thrown into the

landfill. On another day they may all be good enough or almost perfect. The

chance is one the lens maker always has to take and live with the consequences.

The glass manufacturer never takes the glass back, nor will they ever give any

refunds”

Another

possibility is that the focuser has proved problematic. The Stowaway has a 2.5”

Starlight FT with a custom visual back, but for the 110 GTX AP have returned to

making their own – a heavy-duty 3.5”. Now you might point out that

the 130 GTX has an in-house 3.5” too, but it’s not the same

focuser. The new one has a very short body for compactness and

it’s possible they’ve struggled to make it both rugged and

resistant to image shift.

Whatever

the reason, the 110 GTX is an expensive scope: with import duties and shipping

about the same as a Takahashi FSQ-106 here in the UK, but you’ll need to

fork out for a flattener to go imaging with the 110 GTX. But at least with AP

quality is pretty much guaranteed.

So

am I still going in for the draw? Sigh. Probably…

February

24th 2023: Borg 125FL

Image credit

Digiborg.

This

week, Borg revealed a brand new scope at the Japanese Photo Show, a 125mm in a

super-light OTA. This is an exciting announcement; to explain why I need to

unpack the details.

They’ve

produced larger scopes with ED (not FL) lenses before, but those older ED Borgs

can be of dubious quality. In comparison, all current Borg objectives,

including the new 125mm, are fluorite doublets made by Optron in Japan and all

the FL Borg objectives I’ve seen have been superb.

Currently,

Borg’s largest scope is a 107FL at F5.6. The new scope has a slightly

slower focal ratio of F6.4 (800mm), but that’s inevitable: refractor

aberrations get worse at larger apertures and need slower f-numbers to control

them. So F6.4 is (typically for Borg) ambitious for a 5” apochromat, a

focal ratio you’ll usually find in faster triplets of that

aperture. Borg say this is the largest fluorite doublet Canon produce.

The

question is whether such a large fast doublet will have too much false colour?

I guess not. By using the right mating element and a larger air gap, both the

90FL and the 107FL are well corrected and the 125FL will be too (for context,

Tak’s FS-128 was very well corrected at F8, but was foil-spaced and used

an older mating element).

Borgs

are mainly aimed at imagers and the 125FL will work with Borg’s current

0.7x reducer to take it down to a super-fast F4.5 (that’s faster than

either an NP-127 or even a FSQ-130 natively) with good coverage at full-frame.

But,

taking their cue from Tak’ and AP among others, Borg also intend to offer

a dedicated 1.0x flattener with a whopping 55mm image circle for even larger

CMOS chips and those brave souls using their Hasselblads

for imaging.

The

good stuff doesn’t end with the glass: the 125FL will use a special

carbon-fibre composite, with a scratch-resistant textured finish, for the tube.

Borg are specialists at doing small and light, so how much will the 125FL

weigh? My Twitter feed says under 4Kg which would be just amazing for a

5” APO.

The

tube will have the same 115mm diameter as their current largest for backward

compatibility and the photo shows it with the existing large M75 helical

focuser (part 7875 if you’re interested).

The

125FL is slated for release this year and for me it couldn’t be more

timely: a super-light 5” is exactly what I need. But there’s a

problem. My tiny 55FL setup cost about £1500, so I imagine the 125FL will

be very expensive.

February

15th 2023: Vixen’s New PF-L II Polar Scope

I’ll

write a full review when I get the chance, because I’m impressed with

this updated polar scope for Vixen’s AP and SX mounts.

Polar

scopes are a pain in the neck (often literally), but they offer quick and

precise polar alignment if you can see Polaris. My old one was probably faulty,

but in any case messing around with meridian offsets can be fiddly.

This

new polar scope does away with that, by pattern matching Ursa Major and/or

Cassiopeia: just twist until the patterns are in the right position, then set

Polaris into a scale calibrated to 2040. I found just basic alignment

sufficient to get perfect tracking for exposures of a minute or two at focal

lengths up to a metre on my SX2, but for proper alignment you can set Delta-Umi

and 51 Ceph into their own scales.

The

polar scope is easy to use too. It has plenty of eye relief and positive

focusing. The eyepiece has a rubber bumper ring so as not to scratch my glasses.

Illumination is by an internal red LED with fine brightness control that turns

off after a few minutes to save leaving it on and draining the battery

(inevitable otherwise).

Build

quality is first rate too, but then at ~£260 it’s not cheap.

February

7th 2023: Zeiss’ old 8x32 Victory FLs

Zeiss

old 8x32 Victory FLs were a Scope Views best buy for years and one of my

all-time favourites. Their replacement as Zeiss’ premium 32mm

bino’, the 8x32 SF, is good but very different. Now the 32mm SFLs (see my

post here from a few weeks back) promise similar characteristics to the FLs and

I’m curious to compare them, so I bought an old pair of FLs in advance.

I’ve

been taking the FLs hiking most days and they’ve reminded me what a great

binocular they were (and still are): unbeatably small and light, with a wide

bright detailed view, good eyepiece comfort and a superb focuser that’s

as fluid as the SFs’ but even faster. This pair has seen some heavy use,

but remain optically and mechanically as good as new (better, because the

focuser has freed up: even more fluid but losing none of its precision).

Zeiss

really knocked it out of the park with the little FLs and it will be

interesting to see how the new SFLs compare; they have a lot to live up to.

Meantime, used prices for the FLs have finally dropped and they make a great

used buy.

January

29th 2023: Keep It Dry

It’s

obvious you should keep your optics dry, right? Well, given the lenses

I’ve seen with fungus or haze lately, maybe not.

The

most acute problem is small dead air spaces like the air-gap in air-spaced

objectives that trap moisture. Condensation gets in when you take cold gear

into a warm house or car, but also if kept indoors in a steamy kitchen or

outdoors in observatories, sheds and garages. I once saw a £40,000

Takahashi rig (EM500 + Mewlon 300 + FS-128 + 5”

Hα filter) destroyed after just a year in a little dome

set straight onto earth, but even ones on a proper concrete pad with a damp

membrane can suffer. I kept a dehumidifier running 24/7 in my own observatory

and it kept things perfectly dry – buy a decent one, I found

Mitsubishi’s excellent.

Always

store your optics with silica gel desiccant in the case. You can buy the little

pouches cheaply on Ebay or Amazon, but not all are

created equal. Some have a Tyvek outer and can be safely microwaved to

re-activate once they’re saturated. I’ve recently discovered the

large ones intended for cars, see above, which are an economical way of getting

lots of gel in a robust pack.

I

strongly recommend putting a desiccant plug in the eyepiece holder of your

focuser to keep the inside of your scope dry. Annoyingly, these are not as

widely available as you might think. Starlight Instruments make the best, but

it’s out of stock everywhere. If you’re stuck you can make one

yourself by drilling some holes in the bottom of a 35mm film cannister (perfect

fit in a 1.25” hole) and then filling it with little gel sachets (wash

the swarf out and dry thoroughly first).

You

owners of sealed bino’s and scopes are looking smug at this point, but

don’t be. Seals can leak and the outside of lenses can get mould and

fungus which etches coatings; rubber can get mildew and degrade. Always air-dry

your bino’s before putting them away and avoid long-term storage in a

leather case which can house fungal spores.

January 23rd

2023: Zeiss 30mm SFLs

My

little Swarovski Curio 7x21s are wonderful for their size, but are limited to

full daylight and are too small for astronomy.

The

smallest general purpose binoculars that work for nature viewing or birding at

dusk, or some casual astronomy, are in the 30-32mm size, but premium models

– Zeiss’ SFs and Swarovski’s NL Pures

- are relatively large and heavy.

Meanwhile,

Swarovski’s 30mm CL Companions are good but the view and handling

aren’t up to high-end standards. Nikon make the venerable 8x30 EII porros, but they’re relatively expensive now and neither

armoured nor waterproof.

What’s

needed is a modern premium binocular that’s truly small and light.

Zeiss’s ultra-compact Victory FLs once filled this niche and were a Scope

Views Best Buy, but they’re long discontinued and getting less available

used.

Enter

the 30mm version of Zeiss’ successful and excellent SFLs. These are (almost!) as

small as the Victory FLs and even lighter at just 460g – the lightest

premium binoculars I know of outside the folding class. What’s more, they

boast top-quality optics and mechanicals and have decently wide (65° apparent) fields and promise good eye relief of 18mm

too.

I’m

looking forward to reviewing them and might even by a pair for myself!

January 7th

2023: Cost Cutting

Every

year I buy a Christmas pie from Fortum and Masons on London’s Piccadilly.

Fortnums is expensive and their Christmas pie has

always been suitably fancy – like a beautifully cooked turkey dinner with

all the trimmings in a pie. But not this year. With too much dark meat, too

much gelatine and voids and without the decoration on top, it’s clearly

been a victim of cost-cutting.

This

week I treated myself to a brand new pair of Swarovski 12x50 Els (from a UK

main dealer) and I’m rather afraid the same thing has happened. Gone is

the nice semi-rigid case. In its place a simple fabric bag. A bar of that soap

from the NL Pures is no substitute.

Much

more troublingly, though, this pair had an optical problem. Fine by day, they showed a

nasty smear of light running vertically from a first-quarter Moon across the

whole field. Investigation with an LED revealed bad prism spikes in the right

barrel (above). All roofs do show some spiking on the brightest lights, but

this was much worse than usual. I sent them back to the (fortunately most

obliging) dealer for a replacement.

The

replacements are an older pair and have the nice size L case that SW

won’t even sell as an accessory any more (and no soap). Spiking on the

LED is minimal and the Moon perfect. Stray light is much lower overall and star

images tighter. It’s the great bino’ I reviewed and want to own.

I

hope the combination of cost-cutting on the accessories and the optical fail

are a coincidence, but there’s a moral here: buy from a reliable dealer

and test your new purchase carefully and without delay.

December

28th 2022: Where have all the Monos gone?

Some of

these planetary eyepieces are becoming rare.

I

noticed a post this morning wanting TMB Monocentric eyepieces. I’ve been

looking for a 4mm for a while myself, and not only. I can’t find a

Tak’ 2.8mm Hi-Ortho’ anywhere. Meanwhile, the price of Pentax XOs

has soared way above original list and sure enough my contact in Japan tells me

they’re rare and expensive in their homeland too. Even the once-common TV

2-4mm Nagler Zoom is hard to find.

A

few years ago, classic planetary eyepieces like these were readily available;

not anymore.

Takahashi’s

multi-flattener is a clever way to save on kit if you own several Takahashi

fluorite doublets (except for the Sky90 and FOA60 which use a different lens

design). You just need the inexpensive spacer (‘CA’) ring for each

scope. Originally, Tak’ brought out seven CA rings to fit a range of

scopes, new and old. But we’re already down to five: I went to buy one

for my FC-50, only to find it’s discontinued, even in Japan. I snapped up

the ring for my FC-60 because it’s been discontinued too.

Try

finding a pair of Nikon SE bino’s – same story.

It’s

a reminder not to assume long-term availability for the gear you want: high-end

optics are often produced in small batches and when they’re gone

they’re gone. Some are replaced by a newer equivalent but not always (AP

Stowaway F5 anyone??)

December

18th 2022: Telescope or Camera Lens?

This image

of Venus is distorted by decentred elements in a Samyang 24mm F1.4 lens.

Camera

lenses and telescopes are functionally the same; but the way they do it is

different, despite some recent telescopes that blur the line (the WO Cats come

to mind). This was brought home to me by a recent viewing session with an old

friend, comparing various scopes on Mars and Jupiter.

I

had been told that Takahashi’s FSQ scopes, four-element Petzvals based on an old camera lens design, are a bit

compromised for high-power visual use – that they are essentially just

camera lenses. Our planetary viewing session proved that’s not true. The

FSQ-106 gave good views of Mars at 200x, if perhaps slightly less sharp than a

fluorite doublet FC-100D alongside. Meanwhile, the little FSQ-85, equipped with

its 1.5x extender, excelled: views as sharp and colour-free as the finest at

this aperture, arguably better than a TV-85 for example.

I

shouldn’t have been surprised. I’ve spent a lot of time with a

different four-element Petzval, the Tele Vue NP-101, which is an excellent

visual scope and produces fine images too.

No

camera lens could do this, even if you could fit an eyepiece. For one thing,

camera lenses typically have lots more elements to achieve an even faster focal

ratio, elements whose centring is often slightly off (sometimes too much so

even for landscape astrophotography – see above). But more fundamentally,

I’ve read that camera lenses are fabricated to an optical quality of

about one wave – ¼ of the usual minimum for astronomical

objectives.

Of

course, camera lenses are plug-and-play in a way that few imaging scopes are.

Anyone trying to get the flattener spacing just right with a Borg system will discover

this. Still, Takahashi’s achievement in making an ~F5 camera lens that

will also give high-power views is real. And for imaging, a good telescope with

a flattener (whether built-in or not) and a precise focuser still has an edge

over any camera lens for pin-point, low-bloat stars across a wide field.

December 11th

2022: Zeiss SFL: Made in Japan!

To

avoid preconceptions, I make a point of trying not to read forum posts

or other reviews of new products before I review them myself. So I was genuinely

surprised to find Zeiss’ new SFLs are Made in Japan: something of a first

for a top-line Zeiss birding bino’. But does it matter? Maybe.

Around

the time as I was finishing the review, I got an email from a reader whose

Canon binoculars’ armour had deteriorated and Canon wouldn’t

(couldn’t?) repair them. The owner was surprised and disappointed but

honestly and sadly I wasn’t, because I’ve struggled with repairs to

optics made outside Europe (even more so when outsourced to another company).

And in fairness, I do always point out in reviews that Canon’s IS

bino’s – much as I like them – are an electronic consumer

item, i.e. not something with an indefinite life.

Don’t

misunderstand me, I love stuff made in Japan. Between Canon, Takahashi and

Vixen, a lot of my personal optics are Japanese (though not my birding

bino’s). The trouble is distance. Japan is a long way to send stuff for

repair, but outsourcing also means operational distance between the

brand and the manufacturing of its products.

Leica

and Swarovski have repair facilities on site with a huge library of spare parts

and employees dedicated to repair of their products and only their products. No

3rd party manufacturer can do that. And because they know

they’ll have to provide support long into the future, they design for

repairability.

The

upshot is that if the armour on your Swarovskis (or Leicas) perishes out of warranty, you can get it replaced

easily, quickly and cheaply (I was quoted £40 by Leica); on your Nikons

or Canons or Fujis or Kowas maybe not so much.

I really liked the SFLs, but this is an issue I’d consider before

purchase, especially for birding bino’s that will lead a hard life. I’m

sure Zeiss have made unusual efforts to ensure they can repair the SFLs, but

the question of long-term out-of-warranty repairs is still moot IMO.

There

is also the question of whether you should support a European brand and

employer outsourcing its production, but that is a separate issue and a very

personal decision.

November

29th 2022: Why I’m Excited about the new Astro Physics 110 GTX

Image

credit: Astro Physics inc.

I

don’t often visit the Astro Physics website, but recently I went looking

for an accessory for my Stowaway and stumbled across an announcement from

earlier this year – AP is releasing a completely new model, the 110 GTX.

Not

only is this a rare event (even the most recent Stowaway is a reboot of an

existing model), but the 110 GTX is pretty much my dream scope from AP

because it’s effectively their famous Traveler (my review here) re-invented.

The

Traveler is one of my all-time favourites: a 4” refractor (actually

105mm) in an incredibly compact package that slips onboard and does everything

when it arrives. The 110 GTX promises more of the same, but with even better

correction, a better focuser and 5mm more aperture. Sounds exciting, right?

Let’s look in a bit more detail…

The

basic facts are these: the 110 GTX is a 110mm F6 triplet that’s the same

size and weight as the Traveler, despite the extra aperture and has a special

(super compact) 3.5” AP focuser. The tube and sliding dewshield are the

same style as other recent APs like the Stowaway and 130 GT. For some idea what

to expect, read my review of a recent Stowaway here.

What

really impresses me is that the 110 GTX is an imaging machine that’s also

designed for observers. Most small refractors these days are optimised for best

correction at shorter wavelengths for imaging. The 110 GTX is designed to

remain diffraction limited across the whole visual spectrum, from deep red to

violet – from O stars to Mars.

This

being AP you can be confident that everything else, from the homogeneity of the

glass to the fit and finish of the tube, will be absolutely first rate. Cost?

They haven’t announced it yet, but I’m guessing ~$5-6000 incl. case

and rings.

The

only problem is going to be getting one. As for my Stowaway, it’s going

to be a draw and they’ll send instructions to anyone who signed up, after

which you’ll have to act fast to enter. For reference you can read about

the Stowaway draw and order process here. You can find more info on

the 110 GTX at AP’s website here.

Good

luck if you’re entering the draw (on second thoughts to hell with that

cos I want one!)

November

21st 2022: Time for Mars

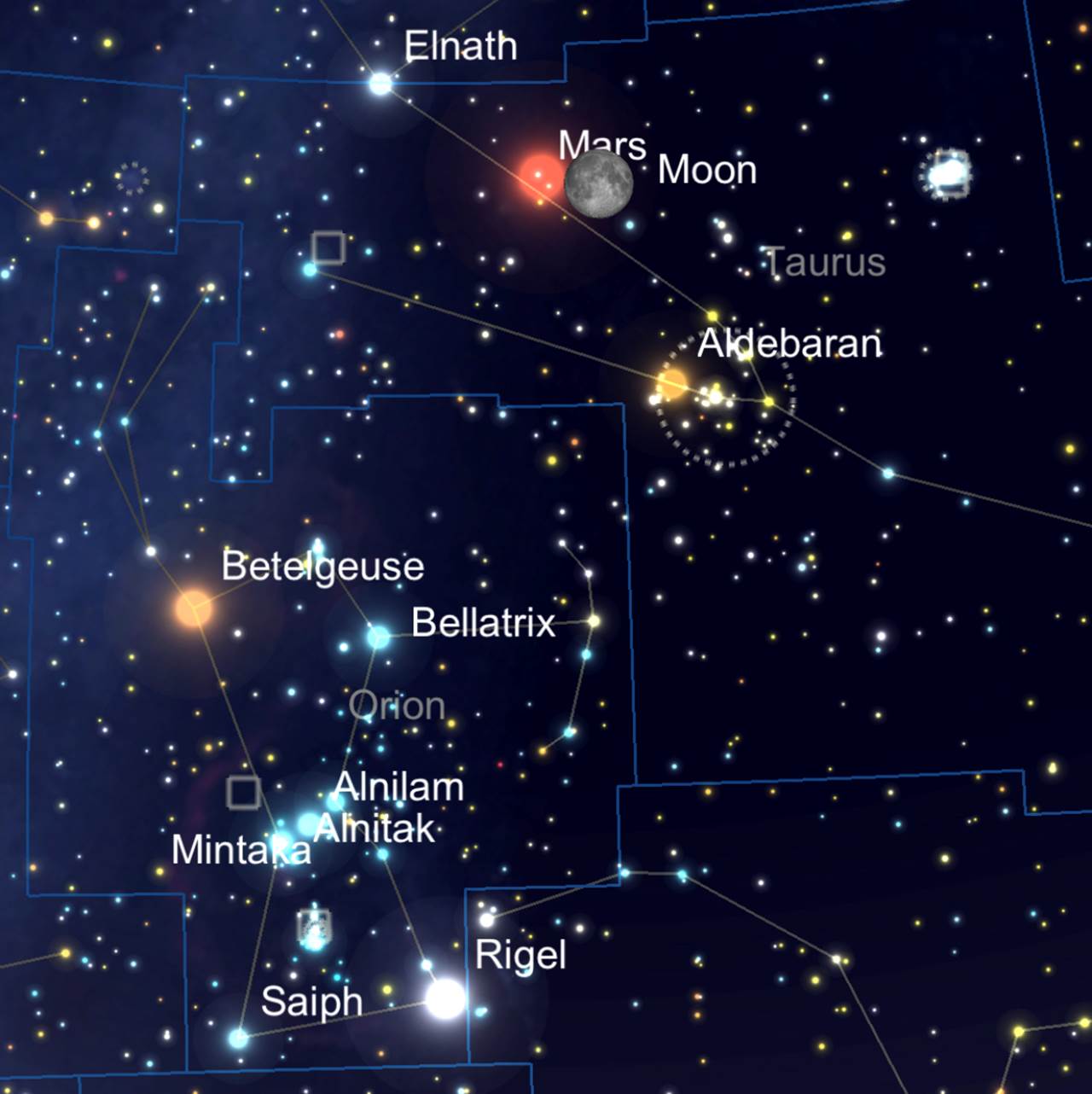

Mars at

transit on opposition day.

It’s

Mars opposition time (when Mars is closest to Earth and best for astronomers) and

there’s good news and bad.

The

good news is that this opposition by far the most favourable of recent years in

terms of altitude for northern observers: right now, Mars transits at about

60°. This matters because you’re looking/imaging

through less wobbly atmosphere. Back in 2018, the opposition from here was at a

virtually unobservable 6°

altitude: even

if you could set your scope that low to the horizon, the thick atmosphere

between you and Mars meant the Red Planet was just an orange fuzz.

Also

potentially interesting this year is that on opposition day, Mars will be

occulted by the Full Moon at about 04:55.

The

less good news is that this year’s is not a very favourable opposition in

terms of closeness and so apparent size. At the moment, Mars is 16.9”

across and will make 17.1” on opposition day. But by Christmas it will

already have shrunk to 15.6” and will be down to 11.5” a month

later. Realistically, this means only another six weeks or so to get the

best views and images. In comparison, that 2018 opposition saw Mars get up

to 25” apparent size. You can’t have it all.

Remember,

Mars is the only planet where you can see surface markings, so just get out and

image/observe if you get a clear night over the Christmas holiday period (but

don’t try observing after a few drinks – I’ve dropped

eyepieces that way).

The

raw opposition facts for the UK are these:

Mars

Opposition Date/time: 8 December 04:26

Rises:

3 pm

Transits:

Midnight / 60° / 17.1” / Mag -1.9

You

can find some more info and tips of gear for Mars in the latest of my

‘How to’ articles here.

November

14th 2022: A Scope for Planets and Terrestrial?

I

recently had an interesting question from a reader that got me thinking and

prompted me to write this post.

The

planets are in the sky again and we’re headed for a Mars opposition in

early December, one that’s better placed for high-latitude observers than

recent oppositions. Perhaps that’s why the reader contacted me to ask for

a recommendation on a quality scope for terrestrial use that could work for

planets too. Hmmm…

This

is a difficult one. For terrestrial use and some casual astronomy, the

best terrestrial scopes can work well. I’ve had good experiences with

Zeiss Gavia and Harpia models for the Moon and

basic deep sky. Trouble is such scopes are too low powered for the planets and

their prisms can smear the light too much.

Small

astro’ refractors are successfully used by some for terrestrial viewing,

with small Tele Vues particularly popular, perhaps because they are so rugged; but

the TV-85 is probably the only one

that might deliver convincing views of Mars. Meanwhile, the wonderful-for-planets

Tak’ FC-100DZ is just too large; but the much

more portable FC-76 does work well for planets

despite its modest aperture. A classic Vixen FL80 could work – it’s light, rugged and of very high

quality with decent aperture. A Questar Field Model could be a great choice, if its narrow

field works for your terrestrial viewing.

The

very best option I can think of is perhaps AP’s outstanding Stowaway 92mm, but they’re difficult to get hold of. Any

other suggestions? Let me know…

October

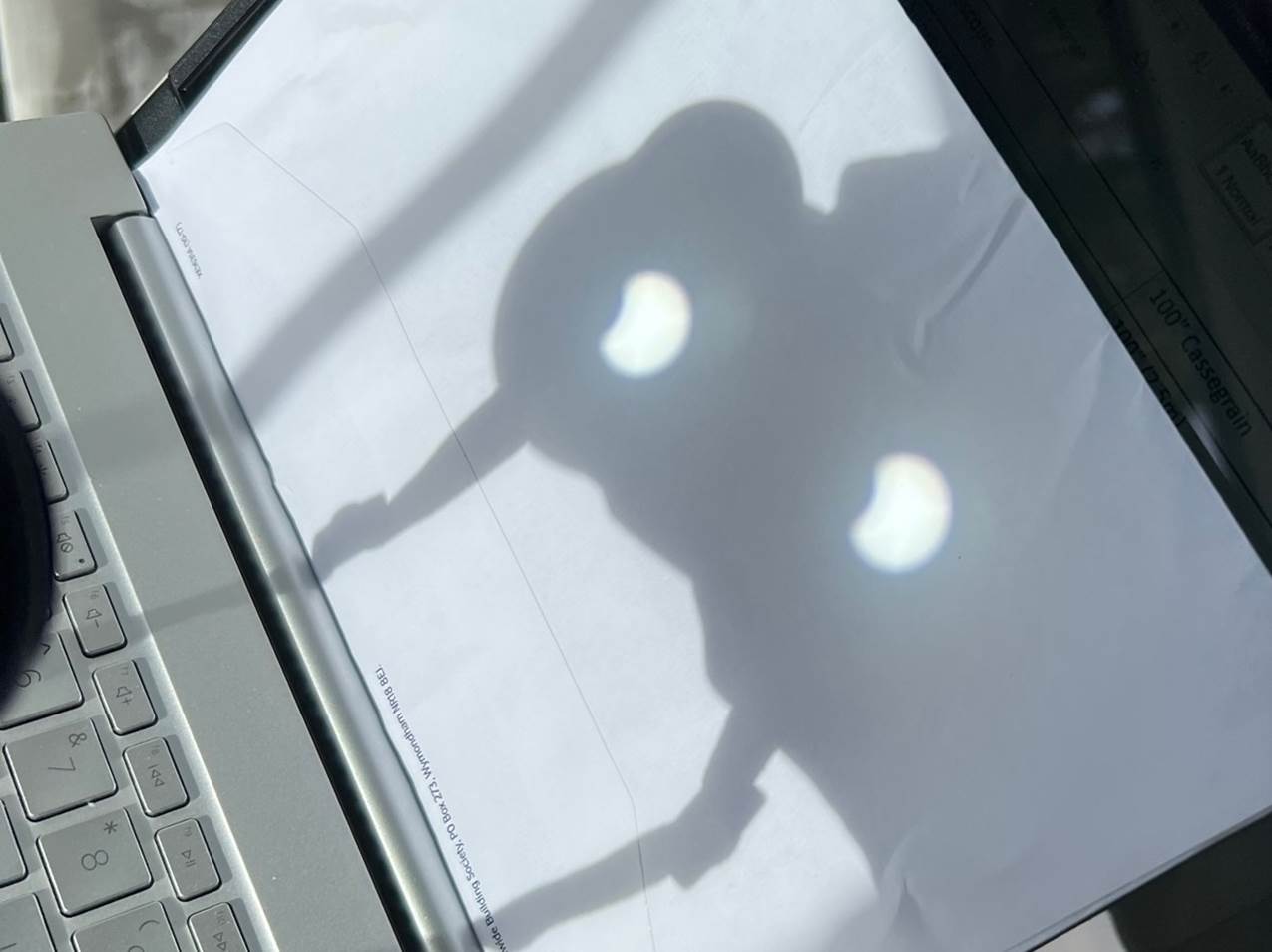

25th 2022: Simple Astronomy

Ever

had a simple meal you enjoyed more than a Michelin star? Astronomy can be like

that. There’s a lot of expensive gear on Scope Views, but the most basic

astronomy can be the most fun and spontaneous.

Today’s

partial solar eclipse was a reminder. I’m away in London with nowhere to

setup a scope and camera, so for once I just projected with bino’s and

snapped away at a partially clouded Sun with my phone. It was fun! What I

should have done for the 2017 US eclipse, instead of fiddling about with

cameras.

Reminded

me of the 1999 Great British eclipse, which was partial in London (and mostly

clouded out for totality in Cornwall). Conditions were similar – I bunked

off work and just projected it with my bino’s between the clouds.

I

sound like a lifestyle guru (ugh), but sometimes best to live in the moment.

A

starry night can be like that too – at its best with just a dark corner

and a pair of bino’s. Enjoy your imaging rig and specialist eyepieces,

but don’t lose sight of the simple, immediate beauty of the sky.

April 24th

2022: Ethical Optics Shopping Post-invasion

Czech Meoptas and Japanese Canons – alternatives to Made in

PRC.

My

1960s Hacker valve (tube) radio is in for a service. It was made in Maidenhead,

but not only: just about every component is British. Nowadays no radios are

made in Britain, all are made in China. This is true of most optics too. We

take this outsourcing of manufacturing as a given, but should we?

The

shift of optics manufacturing to China has largely happened in the eighteen

years or so I’ve been reviewing. It’s made high-performance

bino’s and telescopes available at much lower prices and forced the

high-end to innovate and compete. All good then?

Trouble

is, China’s aggressive posturing on Taiwan very sadly (because I admire

Chinese culture and industry) makes them look more foe than friend now. Is our

addiction to cheap Chinese products a national security risk like our addiction

to Putin’s oil and gas, then? Some analysts are saying so.

Contentious

perhaps, but personally I’ve started to look at where the goods I buy are

made.

So

what’s the situation with optics? Mostly it’s just at the high-end

where it’s possible to avoid Chinese manufacture (feel free to contact me

if I omit something or get it wrong):

For

bino’s, Swarovski is the most straightforward – all are made in

Austria. I believe all Leicas are made in Germany or

Portugal. High end Zeiss are still German or Japanese, but the Terras are made

in China. I believe Steiner are still German made (I really must review a

Steiner!)

High

end Vortex are made in Japan, ditto some Nikons and Kowas,

some Canons (?), Fujis and perhaps Minox too. Meopta are staunchly Czech of course (see above).

In

terms of astro’ scopes, AP and TEC are all U.S. made, whilst Tele Vue

makes its optics in Taiwan and Japan. I think Orion Optics still makes its reflectors

and catadioptrics in Crewe (UK). Some Vixen products are still made in Japan. Takahashi

are still entirely Japanese made, as are Borg to my knowledge. The proverbial

elephant in the room are LZOS lenses, which is a real blow for me as

they’ve always been among my favourites: they probably won’t be

available now since LZOS is a Russian defence contractor.

As

for the future, if this terrible war widens into a global conflict who knows?

Perhaps the West will have to start mass-producing its own stuff again, optics

included, but that would be hugely inflationary.

Feb 12th

2022: More Big Scopes to Look Through

I’ve

just returned from another US astro’ road trip with some inspiring

big-scope viewing, so it’s on my mind. Then I received a kind email from

a reader who likes my descriptions of looking through big observatory scopes.

That’s great ‘cos it’s a become a bit of a pre-occupation for

me.

Views

through the biggest scopes aren’t always as amazing as you’d expect

(which can be interesting in itself), but sometimes they really are. Highlights

include: masses of structure in the Crab and Spirograph nebulae plus the moons

of Uranus through the Struve 82” at McDonald (above); Hubble-image detail

on Mars, Galileo Regio on Ganymede, Saturn’s Encke division and the

Alpine Valley Rille with the Mt Wilson 60”.

My

big-scope views have all been either through century-old instruments from the

golden age of visual astronomy, or through smaller (16-36”) modern RCs

bought or re-purposed as mixed-use outreach instruments. But I’ve just

discovered a third possible pool of large telescopes for observing.

In

the sixties, NASA funded several large long-focal-length classical Cassegrains

for lunar mapping to support Apollo. With small fields of view and slow photographic

speed, these aren’t ideal for modern astrophysics, but would make great

visual instruments.

I

know of one – the 61” on Mt Bigelow, part of the Steward

Observatory – which has had an eyepiece in it. Great solar system reviews

were reported. But there are others, for example the 31” NURO telescope

at Lowell’s Anderson Mesa site. Meanwhile, Lowell’s 72” Perkins

Telescope is also a long-f Classical Cassegrain and seems to be struggling for

work at a super-cheap $800/night, a sum easily exceedable

with a public observing session.

I’m

hoping that if some of these fall out of professional use, their owners will

consider converting them (at least part-time like the Struve 82”) for visual

outreach, allowing new generations of astronomers to witness with their own

eyes what they could only otherwise see in photos.

Jan 13th

2022: Is Software Eating Your Bino’s?

Stock Sony

image.

I’m

a believer in the maxim that profound tech’ changes are overestimated

short term and underestimated long term. So when a WSJ journo’ wrote

‘Software is eating the world’ a decade ago, everyone got excited

for five minutes, concluded ‘yeah, not really’ and moved on; long

term, he was undoubtedly right though.

So

what about our little world of optics then? One famous reviewer was predicting

electronic (i.e. fully sensor-based) binoculars even back then and such things

do exist in the form of Sony’s DEVs. They haven’t caught on yet,

mostly because they’re still very expensive. But a couple of things

converged this week to get me thinking that’s the future, like it or not.

The

first was a message from a friend who’d discovered his new iPhone now did

astrophotography using automated stacking. I’ll doubtless buy one soon.

Software is inexorably eating my DSLR.

Then

a reader emailed me to say something that’s been troubling me for a while

too. He’d loved the view through a pair of NL Pures,

but feared he’d spend big on them only to reach for his stabilised Canons

every time he actually went out to view.

Same.

You see, I’m off on another observing trip soon (fate and irony willing)

and I’ve decided to pack my Canon 12x36 IS bino’s again. You might

find this surprising, since the 12x42 NL Pures are

currently my favourite ever binocular view. But in reality, stabilisation just

reveals more, even if the view isn’t as wide, beautiful and immersive.

Last time I was able to spot the historic V-2 bunkhouse deep in the White Sands

Missile range with the 12x36s. With the NL Pures I

probably wouldn’t have.

Hopefully

as part of this trip I’ll re-visit Lowell Observatory (if it re-opens in

time), where one of their outreach instruments uses an integrating video camera

to give near-real-time views of DSOs that the naked eye never could.

Put

these things together and I suspect that by 2035 most serious binocular users

will never see actual light from the thing they’re viewing. Amateur astronomers the

same. I’ll moan that this is somehow the march of Meta - RL replaced by

VR. I’ll keep a few pieces of cherished optics. But when I go out to

view, it’ll be through some combo of optics, sensors and processors. All

driven by software, of course.

Dear

Sony, please could I have a pair of DEV-50s to review ‘cos I can’t

afford them (yet).

Dec 18th

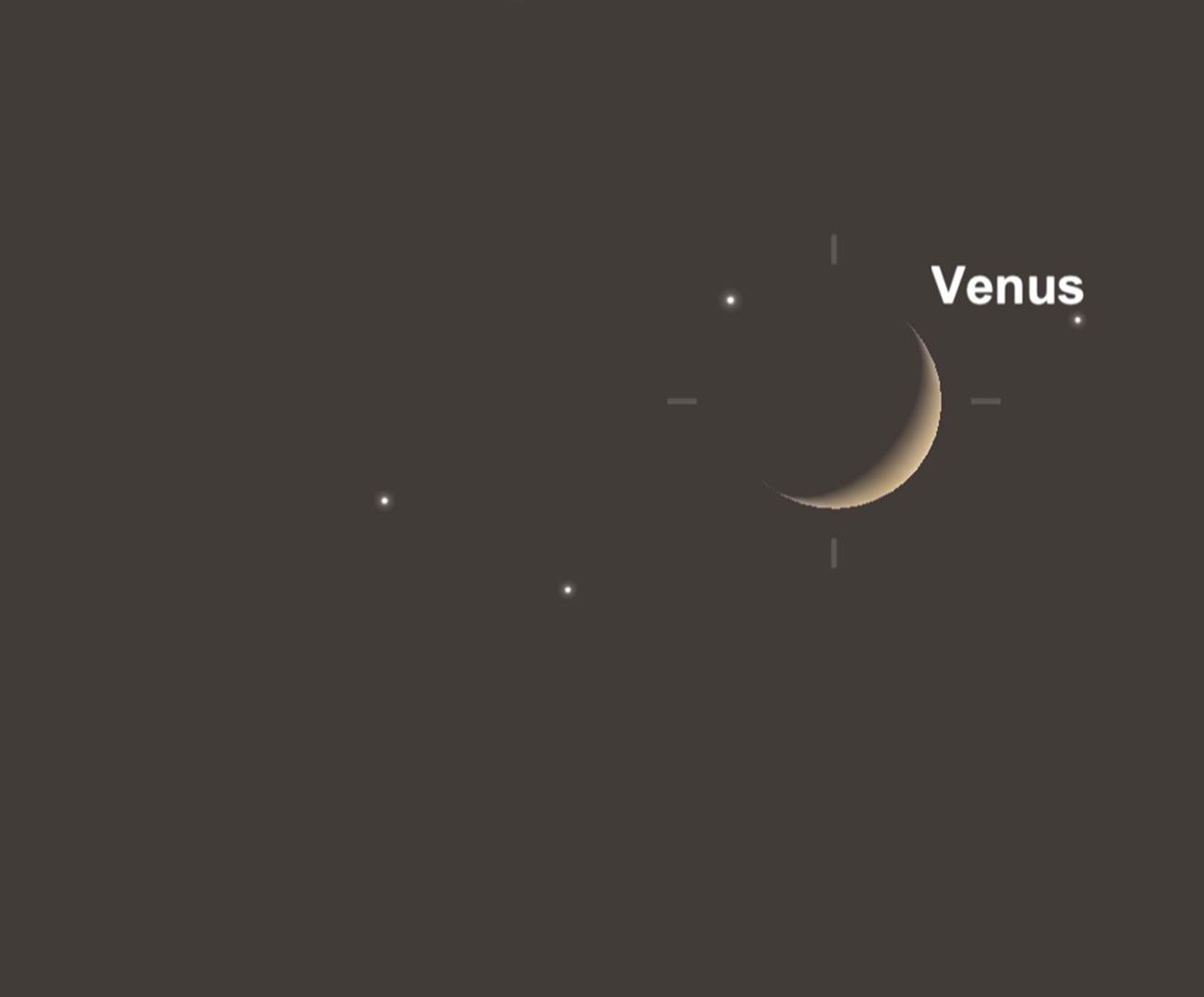

2021: Can you see Venus’ Crescent tonight?

“Can

you see Uranus?” is a popular question when I’m astronomising

publicly, but a more interesting question is “Can you see Venus?”

Well,

obviously you say. But what I mean is can you see its phase? With

your naked eyes? I’d read that it’s possible, but never

convinced myself.

Then

yesterday, on a cold but very clear night testing some scopes at the top of our

local fell, we were looking at Venus setting into the orange sunset over the

sea and my wife suddenly announced that she could see the crescent.

So

I squinted and strained and... no, not really. Well, maybe.

It

got me wondering, how many people can do this (my wife does have excellent

vision)? The thing is that now, when Venus is close and large (52” as I

write) and a thin crescent, is the ideal time (see above for its simulated

phase for tonight).

So,

give it a try! It’s a great example of how you can have a lot of fun

doing astronomy with no gear at all. You’ll find Venus as the brightest

star by far, low in the west just after sunset.

If you can (or if you can’t) make out the crescent with your naked

eyes, please let me know. If I can get enough responses, I’ll publish the

stats.

November

27th 2021: More of this please!

This

is the first blog post I’ve made in six months. That’s not because

I lost interest or had nothing to say. I’ve just struggled to find any

free time at all over summer and early autumn. Really? Really. You see,

2021 has been the busiest and most stressful year I can recall. Full-on

doesn’t even touch it.

Most

recently the culprit has been a tentative return to education, or so I

supposed. It’s something I’ve wanted to do for years and to make up

for lost time I threw myself in at the deep end. It’s been rewarding

certainly, but hugely time consuming.

But

the course hasn’t been my main problem this year. To say I’ve sold

one home and bought two others doesn’t begin to account for a hell of

multiple moves and the aftermath of endless paperwork, DIY and decorating. And

all that following a short but “interesting” period of homelessness

in hotels with no astronomy at all.

What

has this to do with ScopeViews? Everything really,

because that’s what precipitated it all.

Low

planets in recent years compounded the problem of living in a valley with high

horizons. Meanwhile the trees in the woodland to the south had grown taller ...

and taller. So my permanent set-up just wasn’t getting as much use as it

had. Free time had already become a problem too: maintaining my ageing house

and large, high-maintenance garden were swallowing much too much of it:

“I don’t want to repair the damned terrace, I want to go watch an

eclipse from the Atacama!”

Then

I had a bit of an epiphany.

Before

lockdown I had been doing quite a lot of travel to dark sky sites and

observatories, mainly in the US. It had made me realise just how poor my seeing

often was: quite dark but often too turbulent for high magnifications. Then

there was the weather. Britain is famous for rain anyway, but up here it can

rain for weeks. Finally, living so far north means no truly dark skies at all

in late spring and early summer.

Then

on the last trip to the US I enjoyed night after night of clear, dark and

steady skies, with incredible birding and nature viewing by day. I wanted more

of that, a lot more.

So

I made the (very) tough decision to let my permanent setup go – at least

for now - and return to peripatetic astronomy, with more time and opportunity

to travel - to great skies yes, but for birding and nature viewing too.

How

will this affect ScopeViews? More astronomy travel, I

hope - to dark sky sites and observatories; eclipses too. More reviews of

smaller, more portable gear, including an AP Stowaway at last! More viewing

through the remaining big visual instruments from the Edwardian golden age of

visual astronomy. More reviews of binoculars from the very best and most

challenging locations.

Exciting

times ahead, fates willing of course.

April 29th

2021: Elon Musk is an alien, ‘obv’

– and this week proves it

I

love Elon because IMO he’s the only hope for humans on Mars in my

lifetime. Many people hate him, though, and one reason is that he refuses to

behave. Specifically, he refuses to play the part of august and serious CEO and

VIP. And in that refusal, he subverts and devalues those things. Elon can be

downright childish and un-PC; worse, he’s not remotely sorry.

This

week was a perfect example. Someone, no one like the rest of us, tweeted to ask

if he’s alien. Elon tweeted back, ‘obv’.

But oftentimes, when serious journo’s ask serious questions about his

giant business empire, he doesn’t even bother to respond. Aaaaarrrrrgh!

But

in a way, that ‘obv’ was true. Because in

a way Elon really is an alien and this week’s events prove it. Because

whilst most of us slow down as we age, Elon is accelerating at full plaid.

Yesterday

was the fifth anniversary of SpaceX’s first successful booster landing on

a barge; since then, they’ve done it 56 times and counting. This year all

their launches have been on a used rocket. Nine days ago, Starship SN11

exploded in mid-air; yesterday SN15 was already on the pad. Two days ago, the

latest batch of Starlink launched and Shotwell announced near global coverage;

eighteen months ago, ‘experts’ said Starlink was a fantasy.

And

that’s just a week at one arm of ‘Musk Industries’ (think

giant dystopian pyramid and Vangelis at the opening of Bladerunner and hold

that thought).

Today,

Neuralink released a video of a chunky monkey playing

a video game with its mind, whilst mainlining banana smoothy in a virtual

forest. Last summer the naysayers were all ‘Neuralink

is BS’, but today’s casual Elon-tweets suggest life-changing

innovations coming fast for the severely disabled.

Down

in ‘Vegas, meanwhile, the Boring Company has today announced completion

of its first cheap underground rapid transit for the cost of a small bus fleet.

Yes, for now it’s basically Teslas in tunnels,

but autonomous shuttle buses will surely follow. I bought my Boring Company cap

back when it was an Elon joke.

And

that’s not to mention ‘ex-growth-company’ Tesla posting 103%

y-on-y for Q1. But that was ages ago, right? Six days, actually.

How

do you feel about this warp-speed innovation? I love it, obv.

But it really, really winds some people up. Yesterday, a

Tesla-enthusiast tech’ journalist called Joanna Crider was goaded on

Twitter to kill herself by an ex-VW marketing exec.

How

could so much love, fear, loathing, expectation and anticipation, bile and

hatred and yes sheer progress, derive from the humungous dreams of one bullied

South African schoolboy? Is it because Elon really is an alien? Obv.

Wednesday

March 24th 2021: No Bernie, Space Travel isn’t just an

‘exciting idea’

A

couple of my areas of interest collided this week. The first was an eruption in

Iceland, not far from Grindavik in a beautiful if

desolate part of the Reykjanes Peninsular that I’ve visited. Volcanoes

are a lifelong fascination for me and I wrote a book about them. If not for

lock-down I’d have been on a plane to Iceland by now. But it also

reminded me how unpredictable eruptions remain, despite improved monitoring

techniques.

The

predictability problem isn’t really an issue for eruptions like the

current one: modest, gentle effusions of liquid lava like this are the least

dangerous kind and are classified as VEI 0 or ‘Hawaiian’ –

the first rung of the logarithmic Volcanic Explosivity Index.

The

biggest risk is from eruptions at the other end of the scale. The very largest

have a VEI of 8 and are termed Ultra-Plinian (Pliny was a classical author who

witnessed an eruption of Vesuvius). There hasn’t been a VEI 8 eruption

for some 27,000 years, but there are a number of volcanic centres that could

potentially produce one and we might not get a huge amount of warning; even if

we did, there isn’t that much we could do.

You

see, the problem with a VEI 8 eruption is that it would have global climatic

effects, possibly catastrophic ones for human civilisation. It’s an

example of an existential risk that couldn’t be mitigated with known

technology. There are others, many astronomical in nature, including such

diverse threats as a rogue comet or extra-solar asteroid; perhaps even a freak

solar flare.

Then

there are various human risks, such as technology accidents. Such accidents

have been mooted as a chilling explanation for the Fermi Paradox. A leading

expert in existential risk, Nick Bostrom, put it this way:

“It is

not farfetched to suppose that there might be some possible technology which is

such that (a) virtually all sufficiently advanced civilizations eventually

discover it and (b) its discovery leads almost universally to existential

disaster.”

As

I’ve written in a previous blog post, the overall existential risk we

face is surprisingly large, maybe 20% over the next century. Most of the

component risks that can’t be mitigated by any other means can be by just

one – Elon’s goal of becoming multi-planetary. And just like any

insurance policy, it’s too late to buy once the actual risk hoves into view, we have to get started now.

And

that’s why I was triggered by Bernie Sanders’ recent tweet that

space travel is just an ‘exciting idea’. No, Bernie, it really

isn’t. And that belief – that the money is better spent on social

programs and other (genuinely worthy) causes here on Earth - is one that gets

trotted out a lot by the Left. It also happens to be dead wrong, thanks to the

uncomfortable reality of existential risk.

As

I tweeted back, social equality isn’t much use if we’re extinct.

Unexpected Big Nature events, like Iceland’s eruption, should remind us

that our world isn’t quite the safe haven we’d like to think.

Politicians, left or right, should heed the warning; maybe the one from the

pandemic too: civilisation and even human existence is surprisingly fragile and

we shouldn’t have all our proverbial eggs in one planetary basket.

Sunday 21st

March 2021: National Park Clear-cut on UN Forest Day

There’s

a local beauty spot that I use(d) a lot for testing optics: full of wildlife

and birds at close range, it’s got wonderful long-distance views too.

You’ll see the place in my reviews, a mix of wooded crags and forest

paths clustered around a reservoir. Except last Friday they clear-cut it.

Today, two days later, it’s the UN’s International Day of Forests.

The

extraordinary thing is that the devasted landscape you see above lies deep

inside the Lake District National Park, a designated Area of Outstanding

Natural Beauty and a World Heritage Site, famous home of Romantic poet William

Wordsworth.

Now

you’d think that when they need to take timber out of a national park,

they’d use sensitive selective methods, but no. They got in this machine

from John Deare that does just amazing damage – rips up the soil and

under-storey down to a metre across the whole site and leaves it strewn with

smashed wood and stumps like the army tested tanks on it.

I

suspect that Federal authorities would never permit this in a US NP, so why

does it happen here? Jobs? I’d guess a man week per year, tops. Money? If

the whole area yields as much gross profit as a local B&B I’d be

surprised. Carbon sink when it re-grows, maybe? From the volume of smashed

timber left to rot and the soil damage, I doubt it.

It

is, however, typical of the UK’s two-faced attitude to the environment.

This is the same county (Cumbria) where up until last week they were planning

to open a new coal mine. What’s the point of UN Forest Days and Davos

summits if nothing changes on the ground?

Meanwhile,

all the birds and deer I once came to view have departed to leave a wasteland.

But if a local resident wants to change the colour of their front door,

they’ll need planning permission.

Monday 1st

March 2021: I Saw Starlink Last Night and it Wasn’t Good

I’m

a fan of SpaceX, especially their plans to colonise Mars. People think

it’s crazy, it’s not. Experts like Nick Bostrom think the risk of

human extinction this century might be as high as 20%. Elon is right: to

mitigate that risk, we have to expand off-world.

Starlink

is a big part of those multi-planetary plans. Launch services just won’t

fund Elon’s Mars ambitions. And for me Starlink has personal meaning too.

I live in the countryside and our internet is terrible. I was without any

connectivity for three months last year and wasted countless days battling

Vodafone. It’s still almost never good enough for streaming radio,

never mind Netflix. I need Starlink. So I’ve hesitated to join all

the criticism.

I

actually haven’t seen Starlink myself since a year ago when I took

the photo above. Then last Sunday night I did, quite by accident.

I

was testing some Zeiss binoculars in the dark-sky hour before Moon rise, at

about 6:30 p.m. My view was the region of Auriga around the open clusters M36

and M38 (the Pinwheel and Starfish). A satellite shot through from west to

east, then another and another: a continuous stream of them seconds apart. This

went on... and on: Starlink.

The

interesting thing is that those Starlink satellites all followed closely on the

same path, right past bright star Phi Aurigae, so I was able to compare their

brightness. And it isn’t good news. By now, the sunshade and black paint

mitigation efforts have presumably been implemented. But those satellites were

still much brighter than I’d like. In terms of magnitude, Starlink

can’t have been fainter than about 6-7, possibly even 5-6. And there

really were a lot of them.

Even

for a binocular astronomer, Starlink was distracting. If I’d been taking

subs, they would have been useless. Was I unlucky to catch the Starlink train

lower than their target altitude? Maybe. But it’s starting to look like

Starlink – great news for people struggling without decent internet

access – really is bad news for astronomy.

But

here’s the thing. From the press hate you’d think constellations

like Starlink are a plague sent by Elon. They aren’t. Other companies,

including Amazon and One Web aren’t far behind. And as a professional

astronomer recently pointed out – at least Starlink are listening and

trying to mitigate. Will Amazon be as responsive?

I’m

worried ...

Sat 20th

Feb 2021: Is a Flying Tesla just ‘more Elon BS’?

The

press has a short memory, so when it picked up a few Elon tweets about a flying

Tesla this week it acted like this is more capricious fantasy and BS from their

love-to-hate billionaire, dreamed up over a late-night joint. In fact, Elon

first mooted a SpaceX version of the upcoming Tesla Roadster over two years

ago. I know this for sure because Scope Views has had an article about it since

Jan 2019.

In

the latest round of sneer-and-smear, various journo’s have waded in with

their opinions on how impossible a flying Tesla is. Significantly, though, I

have yet to find much analysis of the actual physics or engineering:

‘cos, you know, that degree in Media Studies makes you far more expert on

rocketry then all those SpaceX engineers with PhDs from MIT, right?

Well,

no, actually. As a physics and engineering problem, the question of whether

SpaceX technology could allow a Roadster to lift off, hover at a few metres

above ground, then drift across a car park, is easily analysed. I’ve

updated my original article with some new figures provided by Musk and

it’s clear – like it or not, a hovering Roadster is entirely

feasible from a physics and engineering standpoint. Don’t approve?

That’s a different issue ...

You

can read my updated piece on the physics here (BTW, I’m not a rocket

scientist either. If you are, then feedback most welcome!):

http://www.scopeviews.co.uk/SpaceXTesla.htm

22nd

January 2021: Is Wide the New Normal?

No,

I’m not writing about the obesity crisis (although I did put on a few

pounds over Christmas). Instead, I want to ask myself (and you too) if

we’re so used to wide fields of view that it’s near impossible to

go back.

I’m

shopping for a pair of 7x42s as my regular walking/birding glass to replace the

Zeiss Victorys I regret selling. I was tempted by a

pair of Swarovski Habichts. I tested the 10x40s a

while back and liked them, but the 7x42s are even simpler, even more pared to

the minimum - something that suits my lockdown mood.

I

like the Habichts’ retro’ style and low

price (for a Swaro’). I appreciate the fact

that I could get them serviced locally if necessary. I really like the idea of

a pair of bino’s with only five lenses between eye and view (yes, really

– they have a basic doublet objective and a three-element Kellner

eyepiece), that have unrivalled transmissivity and very low weight as the

result.

The

Habichts’ do have a big downside, though - a

very narrow field by modern standards, just 46° apparent. That means their true FOV is the same as

the 12x42 NL Pures. I’ve tried to convey this

in the title image by showing it on the FOV of the 8x42 NL Pures:

you really do lose a huge area of view. Still, I’d been convincing myself

it’d be fine. After all, that’s how FOVs were when I started

observing. Then something happened to change my mind, when I was out testing a

new scope last night.

In

schizoid opposition to my own advice, I do prefer simpler eyepieces for

monocular planetary viewing with the best telescopes. In particular, I favour

the TMB Monocentric which has just two air-glass surfaces (it’s a

cemented triplet). The difference is marginal, but I think I can perceive it

– a very slightly sharper, more contrasty and richly coloured image of

Mars for example. However, the Monocentric has a narrow field of view as the

price for its outstanding on-axis performance, rather like those Swarovski Habichts in fact.

Usually,

I only ever use the Mono’s for planets, where field of view isn’t

even really noticeable, let alone important. But on this occasion, I swung the

scope from Mars over to the nearby Moon without bothering to swap eyepieces.

And oh dear. I habitually view the Moon with an 80° Nagler or a 100° Ethos because I love the

porthole, lunar-module-window, view. But that narrow FOV just ruined it. Sorry

to sound like a TeleVue ad’, but gone was the

majesty and awe, absent the sense of being Michael Collins alone with the

Moon’s rugged primordial grandeur. Now I was looking at a picture in my

lunar atlas through a straw.

So,

for the Moon at least, I’ve been spoiled. I can’t go back to the

narrow Huygens eyepieces of my childhood Tasco. But what about bino’s? No

coincidence, I suspect, that most of my favourites recently have had wider

fields. The Meopta 7x50s were an exception, but there

it was the hugely comfortable eye relief I loved, something those simple

Habicht Kellners don’t have either.

So

could I live with a 46° FOV in return for light

weight and a super-bright view? We’ll see, as the Zen Dojo said, but

I’m not optimistic.

11th

January 2021: Dreaming of another Astro Road Trip

Early

January just isn’t a great time of year, any year, never mind a pandemic.

But for 2021 we can add Covid uncertainty and lockdown fatigue to Divorce Day

and Blue Monday. This time last year I decided to do something about it, moving

my planned big road trip from the usual spring/summer into winter. It was a bit

of a leap into the unknown. I’ve driven maybe 50K miles in the US over so

many road trips I’ve literally lost count. But I’ve never done one

in the snow and freezing temperatures of a Rocky Mountain February. We Brits

aren’t really used to driving in the snow. How do you fit chains,

anyway (don’t laugh)?

It

certainly threw up a few moments. Snowshoeing and wildlife viewing in the

Yellowstone backcountry at minus twenty, I found myself going all drowsy and

just made it back to the car. I discovered the hard way that tap water plus

motel shampoo just ain’t gonna

cut it as winter screen wash. My first car’s engine warning light came on

in a blizzard south of Billings Montana and I prayed all the way to the airport

Hertz desk. Driving the loneliest road, in pitch darkness and even thicker snow

west of Cimarron NM, a herd of deer leapt into my lane. By the time I reached

Raton that night the snow was so thick I was the only car on the interstate.

Still, I had the best time, from the moment I opened the curtains of my Denver

airport motel onto snowy prairie and a rising Moon.

Icy

trails and birding at Rocky Mountain Arsenal NWR. Incredible big telescope,

dark sky views at Lowell, Kitt Peak and McDonald. I found the Project Paperclip

V2 blockhouse deep in the White Sands Missile Range with my Canon bino’s

and got chased away from the Blue Origin ranch near Van Horn. It was all

spooky-no-Mulder on a weird late night visit to the Marfa Lights viewing area;

lonely landscape astrophotography from an isolated lookout in Arches NP proved

a bit creepy too. I was disappointed not to get a look through the 20”

Clark at Denver’s Chamberlin Observatory, but I’ll never forget the

atmosphere on the observing floor with heavy snow whispering into the pines

beyond the windows. Nothin’ finer than gazing

at an icy Moon through a motel window with a cold bottle of Blue Moon in one

hand, a pack of hot Tapatio Doritos in the other.

Despite

my worries and too much on-piste driving, maybe my

favourite road trip ever. So much so, I’d planned to repeat it this

winter, with a coast-to-coast trip stopping off at more observatories, more

landscape astro’ in the red rock deserts of Utah and Arizona; maybe see

how things are progressing at SpaceX Boca Chica and Spaceport America. Nothing

doing though. Locked down again and all the observatories’ public viewing

programs shut down.

So

here I am, looking at the photos, reminiscing and dreaming when I’ve got

a backlog of binoculars to review.

20th

December 2020: How To See The Jupiter Saturn Conjunction

You’ll

most likely have read about this, so I’ll be brief with the intro’.

This Monday (21st) will see an unusually close conjunction of

Jupiter and Saturn. Planetary conjunctions are fairly common, but ones close

enough that they look like a single star are not – this will be the first

for centuries. It’s particularly timely, too, because a few days before

Christmas it brings to mind the Star of Bethlehem, one theory for which is a

close conjunction just like this one.

So

how to see it? This is a bit tricky, because in northern latitudes Jupiter and

Saturn are low in the south west just after sunset. From London, the pair will

be at just 17° altitude at 1500, dropping

to 14° at 1600. From more northerly areas it will appear

even lower. So for most places in northern Europe, you’ll need a

viewing spot with a clear southern horizon. Realistically for me and many this

will mean up a hill!

You need to be in position and set up (if

you’re using a scope and/or camera) by about 1530 GMT. The best views

will likely be between 1550 (sunset) and 1650. For the most spectacular view in

a dark sky, you might get lucky between 1700 and 1800, but it will be very low

by then (just a few degrees above the horizon).

The

images above simulate the view at 1530 from London. The blue circle represents

a 1° field of view for reference – roughly what

you’d get in a small refractor at about 80x magnification.

If

you don’t have a scope (or can’t be bothered lugging one up a

hill), bino’s should split the pair, whilst the naked eye view should be

a very bright single star.

As

you can see, Monday and Tuesday are almost equally good, but the pairing

diverges rapidly from Wenesday. Still, Christmas Eve

(Thurs) currently looks good for weather and still well worth the effort. If

you’re locked down for Covid, make it part of your exercise walk! Good

luck!

4th

December 2020: Chang’e-5 – Yes, but where the heck is Mons Rümker?

SpaceX

has been getting most of the space news lately, as usual. But one of the most

exciting missions of late 2020 is actually China’s Chang’e-5 to

return a core sample from the Moon. If successful it will be the first time

we’ve had a fresh lunar sample to study since the USSR’s Luna 24

mission in August 1976.

It’s

a complicated mission, involving a two part lander that looks and works a lot

like the Apollo Lunar Module. That Chang’e-5 lander has successfully

touched down and is preparing to launch its sample back into orbit and from

there (hopefully) to a landing back on Earth in the Mongolian steppes.

But

if you’ve been following the coverage, you may have found yourself

asking, ‘touched down where exactly’? The answer is a

‘unique complex of volcanic lunar domes’ (the largest such on the

Moon) called Mons Rümker, but where the heck

is that?

You’d

be forgiven for not knowing, because Mons Rümker is an important

formation, but not a very easy one to find – binoculars certainly

won’t show it and casually observing with a telescope you’re

unlikely to stumble across it either. Mons Rümker is located in the far

north west, in Sinus Roris, just off the limb of the

Moon’s visible face, to the west of the famous Bay of Rainbows (Sinus

Iridium).

I’ve

marked the location on a photo from my own library of lunar phases, taken on

the 13th day of a lunation – the best time to find Mons Rümker. If you want to try to find the place where

Chang’e-5 landed for yourself, the best days of the lunation are probably

between the 12th and 14th days of a lunar cycle. The

domes of Mons Rümker are low and rounded and

show up best when they’re near the terminator (the Moon’s day/night

dividing line), when the long shadows bring them into sharper relief. Your

next such opportunity (and last this year) will be from the 28th-30th

of this month. Try it!

28th

November 2020: Impossible Tech

(The NYT has form here

– a few decades later they said rockets wouldn’t work in space).

I just reviewed

Swarovski’s new NL Pure binoculars. They achieved something I thought was

impossible – a 70° flat field in a

birding bino’. This week, SpaceX launched and landed an orbital booster

for the seventh time; lots of people said that was impossible too. Meanwhile,

the MSM churn out pieces saying self driving cars are

impossible, but I watch a guy called Joel Johnson taking spooky long night

drives completely alone as a matter of routine (Joel’s taken over sixty

now, check this video out, you’ll be amazed):

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=gnqiOVhEZh0

So what’s going on? Of course,

some pundits just don’t know what they’re talking about (looking at

you Rory), but there’s something more profound at work. To understand it

we need to go back almost fifty years.

In 1973 the eminent Cambridge

mathematician James Lighthill published what became known as The Lighthill

Report. In it, Lighthill basically trashed the entire nascent field of A.I. He

later presented a televised lecture covering similar topics. Lighthill based

his arguments on sound maths – he cited the ‘combinatorial

explosion’ inherent in non-trivial A.I. tasks like facial recognition and

natural language processing, even playing masterly chess, as the reason none of

those things were feasible. Trouble is, fifty years later my phone does those

things with free apps. What happened?

Lighthill was certainly an

‘expert’, he held the Mathematics chair at Cambridge later occupied

by Stephen Hawking. His reasoning was sound too, given the technology of the

time. But right there’s the problem.

Saying ‘faster than light travel

is impossible’ is based on a set of equations, a complete physics of the

problem. It could be wrong, but if so the fundamental physics must be wrong in

some way. To claim that facial recognition is impossible ignores numerous

assumptions not about physics but about technology. In

mathematical terms, there are too many variables in the equations, with assumed

values that may be very wrong. When Lighthill refers to a ‘very large

computer’ he means something orders of magnitude less powerful than the

one in my toaster. Tellingly, Lighthill refers to ‘specialised neural

networks of extreme complexity which there is no question of imitating’.

It’s that ‘no question ...’ clause which betrayed him.

I actually think something else was at

work here too – emotion. I think James Lighthill was a brilliant

intellect and took pride in being one. He refers to the ‘uniqueness of

Man’. I think he hated the idea that a machine might be superior at

things he held dear as part of his intellectual pride, playing chess perhaps. I

think you can see this in his lecture – Lighthill may have been

brilliant, but his rambling, populist rhetoric employs cheap sophistry,

including ‘argument by bombast‘ – a sure sign of a shaky

argument since 400 BCE. Lighthill sneers in his cut glass English, the audience

giggles; fate loves irony.

So next time you read a headline saying

some tech’ is impossible, remember James Lighthill.

21st

November 2020: Seventy Degrees - SW NL Pure and TV Panoptic

Almost

exactly a decade ago, I published an open letter to the Alpha bino’

makers, challenging them to deliver the following:

· No visible

in-focus CA

· An

apparent field of 70° or more

· A field

which is sharp, flat, bright and coma-free to the edge

· Eye relief

of at least 16 mm

· Minimal

blackouts (spherical aberration of the exit pupil in technical terms)

· A focuser

as smooth, fast and accurate as Nikon’s HG range

· All the

usual features, such as waterproofing, twist-up eyecups, etc

I’d become fed up with reviewing

astro’ telescopes systems that performed on a different level to my binoculars.

Not long after, Swarovski launched the Swarovision ELs which featured most of these things, except

for the field of view. What we got was 60° - an improvement of just a few

degrees on the best flat field models like Nikon’s SEs.

Now 60° is pretty yawn in the world

of astronomical eyepieces, the entry level for Tele Vue’s range. Back

then they’d just launched the Ethos with 100°, although even I

admitted they’d struggle fitting two of those optical grenades in a pair

of ELs. Still, a quick play with Tele Vue’s eyepiece calculator suggested

a ~70° field from a binocular-spec telescope should be possible with

another venerable eyepiece design, the 68° Panoptic. Specifically, a 19mm

Panoptic (see above) would give about the right numbers with a 42mm objective

of ~F3.5 and crucially it wouldn’t be too large for a bino’ barrel.

So I waited, expectantly, hopefully,

for a 70° EL based on a Panoptic-like eyepiece design. And I waited ... and

waited.

Eventually, we got the Zeiss SF with a

few degrees more than the EL, but still not 70° and not really as flat as

I’d like for astronomy either. Leica’s Noctivid

was no better. I am no optics designer and I started to assume I’d missed

something, maybe prism vignetting or something, that meant it just wasn’t

possible. Then last year, Nikon’s WXs seemed to confirm it. Here was a

10x50 with 70°, but it was gigantic! Maybe my dream of a truly wide field

birding bino’ just wasn’t optically possible.

Funny how things often happen right

after you’ve finally given up. Because a few weeks ago, Swarovski

launched the NL Pure as a successor to the EL as a top-of-the-range birding

binocular. And here in the NL Pure at last was a 70° field, even (almost)

in the 8x model to give a whopping 9.1° true field – the maximum of

any current binocular that I know of. And by the way, the NL Pure finally fully

ticks all of my original boxes too ... just a decade late. Something

good finally came out of 2020.

18th

November 2020: SpaceX Pad Problems

Flame Trench

below Pad 39A, with Falcon Heavy above it, taken by me in 2019.

Seeing

pads 38 and 39A at the KSC up close last year made me realise what massive

structures they really are. And no wonder. Launch pads take one hell of a

battering. When SpaceX took over

historic Apollo Pad 39A at Cape Canaveral, from which Crew-1 launched on Sunday,

they did lots of work to the service structure and built the futuristic new

crew access arm. Less publicised was the work it had needed underneath. The

giant flame trench (see photo above) and deflector had suffered damage and

erosion since the Apollo years and lots of refractory bricks had to be renewed.

Ironically,

given all the new technology in Starship, it now seems it wasn’t the

rocket or its Raptor engines that caused the spectacular failure during a

static fire in Texas a few days before Crew-1, but a much more mundane

technology – the refractory coating half a continent away at the Boca

Chica launch pad.

In

case you missed the event, the static fire – always a spectacular flame

fest – threw up unexpected sprays of huge sparks. Afterwards, molten

metal was seen dripping from an engine and later a one-use valve on the nose

burst to relieve pressure that had been building since the static fire. Many

assumed some engine problem and one of the Raptors was indeed replaced the next

day.

Yesterday,

Elon finally tweeted the surprising root cause of all the trouble: not a Raptor

failure per se, but the coating of Martyte on the

pad, which had smashed into ‘blade-like’ shards that flew up into

the engine bay and severed an avionics cable (Martyte

is a proprietary name for some kind of ceramic coating intended to protect the

concrete). Perhaps we shouldn't be surprised. Those loose Pad 39A bricks are

said to have reached 680 mph during a final Shuttle Launch.

Loss

of avionics then led to all sorts of trouble. First, one of the Raptors

suffered a bad shutdown: presumably the complex full-flow Raptor engine needs a

specific sequence of shutdown events, perhaps to prevent a pre-burner meltdown,

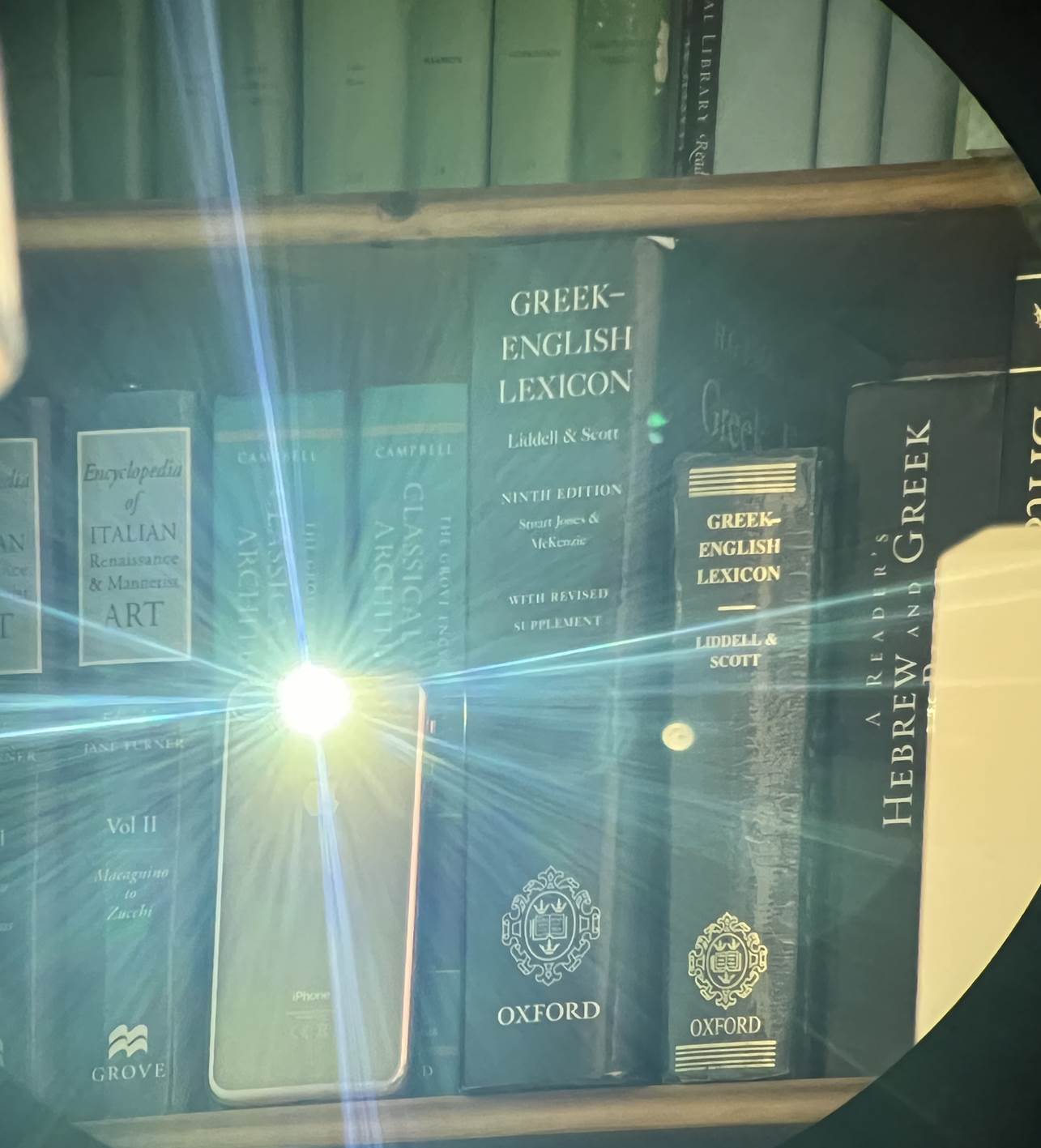

hence the dripping metal. But even that wasn’t the end of it. Next, the