Canon 12x32 IS Review

I’ve owned a pair of Canon’s 12x36s for several

years and used them a lot, mostly for travel and astronomy, but for casual bird

watching and nature viewing too. I really like them as does my daughter who is

usually not a fan of high-powered bino’s. They’re a current Scope

Views best buy for astronomy.

The 12x36s do have downsides though – too much false

colour (esp. for daytime use in bright conditions) and lack of full

waterproofing.

Enter Canon’s latest 12x32s. Similar in size and weight

to the 12x36s (i.e. much lighter than their other high power I.S. models) and

promising advanced new dual-mode stabilisation, I bought a pair to see if a

decade of further development might have produced my ideal replacement for the

12x36s.

At A Glance

|

Magnification |

12x |

|

Objective Size |

32mm |

|

Eye Relief |

14.5mm claimed, ~12mm measured |

|

Actual Field of View |

5° |

|

Apparent field of view |

55.3° |

|

Close focus |

1.5 m |

|

Transmissivity |

90% est. |

|

Length |

174mm eye cups extended |

|

Weight |

780g |

Data from Canon/Me.

What’s in the

Box?

A Canon unboxing remains a prosaic affair compared to the

embossed card and nature art of Zeiss and Swarovski:

Design and Build

The

Canon IS range now (early 2023) has no less than five different groups, though all

share a similar design and look:

· A newish range of 32mm models featuring a

different type of IS derived from their camera lenses, including the 12x32s on

test here

·

Older 10x30 and

12x36 models, which share a similar non-waterproof design, are light weight and

fairly cheap. The 12x36s are a ScopeViews Best Buy

for astronomy.

·

Premium 10x42s

which are fully waterproof, have special lenses and are mainly aimed at birders

·

Large, high-power

binoculars of semi-waterproof design, with ED lenses: 15x50 and 18x50

·

Recent small and

light-weight ‘pocket’ binoculars in 8x20 and 10x20 sizes

Canon

12x36 and 12x32 with a pair of Swarovski EL 12x50s for comparison.

Body

Physically,

these 12x32s share their design and materials with other Canon models. They are

made in Japan, as are the 12x36s and the 18x50s I’ve reviewed.

Not

only do the Canon’s IS models look different from conventional

binoculars, they work differently too. Instead of the whole body pivoting to

accommodate different eye spacing, just the eyepieces pivot. The hinge-less

plastic body has the appearance of an electronic gadget rather than fine

optics, more like a Canon camera in fact. But build quality is very good.

Canon

claim a weight of 780g for the 12x32s dry, a little heavier than the Canon 12x36s.

The

12x32s are almost exactly the same length as the 12x36s – quite a compact

binocular, as compact as many 10x42s. However, the body is much fatter than the

12x36s (possibly to accommodate the new type of I.S.) and a different shape.

The

body is also now moulded in one piece, with the objectives integrated into the

body structure, unlike the 12x36s’. This should help prevent water

ingress. Like the 12x36s, these don’t offer any other special sealing

against water, though. Compare the 50mm models, which are splash-proof and the

premium 10x42s which are fully waterproof.

Like

other Canon bino’s, the 12x32s’ composite body is covered with a

thin rubbery armour that helps grip, but though it isn’t a fluff-magnet

like some it does attract more than the Swarovski’s for example. It has a

slightly different tone of dark grey than the 12x26s, but is otherwise similar.

The objectives are surrounded by thin protective rubber ‘bumpers’

– a thoughtful feature.

Some

readers have reported that Canon’s armour doesn’t wear well and

isn’t replaceable. At risk of repeating myself, treat these as consumer

electronics, not the forever investment a pair of Swarovskis

could be.

Another

change from the earlier models is a different battery housing with a push-fit

rubber cover. It’s a welcome improvement over the old version that needs

fiddling with a coin to open.

Focuser

The focuser on the 12x36s is really

good – light, smooth and accurate. The focuser

on the 10x42s even better, close to an ‘Alpha’ birding bino’.

The 12x32s are slightly worse than either, with a spongier

feel, despite a larger wheel. Precision is good, though.

The reason for the change in feel from the 12x36s may be the

way the focuser works. Both focus by moving the objectives, but the 12x36s move

them externally, whilst the 12x32s have an internal focusing carriage behind a

plane window.

Dioptre adjustment is standard Canon – twist the right

eyepiece against a scale. It’s quite light and smooth in use (unlike the

14x32s’ I reviewed). It’s best adjusted with the I.S. enabled.

These 12x32s focus very close – I measured about 1.5m. But

I couldn’t merge the image at all at this distance, perhaps due to slight

miscollimation on this pair.

Close focus to infinity is just over two turns.

Optics - Prisms

All

the Canon IS binoculars use a type of porro-prism called a porro II that have

cemented prisms.

Porro prisms have an advantage over the roof prisms found in

most modern birding binoculars: they don’t need mirror coatings, so

transmit more light. Porro prisms also don’t need phase coatings to

deliver high resolution.

In my experience, porros can

produce tighter star images with fewer ‘spikes’ than roofs too.

Optics - Objectives

The 32mm objectives lie behind plane optical windows in this

model – the same as the 14x32s (and the 50mm models), but different from

the original smaller one like the 12x36s. The binoculars look like they have

larger objectives because those optical windows are 35mm diameter.

Canon’s specs say that these have an astounding seven elements

in their objectives. Most bino’s have two or three. But this number

likely includes the stabiliser components, see below.

Canon state that they contain a ‘UD’ lens, but

I’m not sure what that means. Probably not ED (or SD) glass, judging from

their performance, even though most bino’s in this price range do

include ED elements to kill false colour fringing.

These have Canon’s premium ‘Super Spectra’

coatings, here with a pinkish-green hue much like the best Alpha brands’.

They are different/better than the 12x36s’ (see comparison photo below).

Inspection suggests all elements are coated to some degree.

Baffling is good, with ridges on the lens rings and in the

focuser carriages.

Canon advertise ‘Super Spectra’ coatings for the 12x32

IS and 12x36 ISIII, but 12x36s’ much more reflective (i.e. worse).

Optics - Eyepieces

The eyepieces are fatter, but have smaller eye lenses than

the 12x36s – they look very like the 15x50s’. Canon state that they

have 5 elements and include a field flattener lens.

Field of view is acceptable, but far from wide at 55.3° apparent, which translates to 5° true. This is the same as the maximum field you can get out

of a Tele Vue 85 scope. For comparison, Swarovski’s 12x50 Els offer a 5.7° field.

Canon claim eye relief of 14.5mm, but I measured about 12mm

from the rim of the folded eye cups. That’s not enough and means I

can’t see anything like the whole field with my specs on.

The usual fold-down Canon eyecups are essentially redundant

here – I need them folded, even without glasses, because

there’s far too little eye relief to see the whole field when

they’re extended. Those rubber cups fold easily, but they are real dust collectors.

Optics – Image Stabilisation

All

Canon’s original I.S. binoculars – from the defunct 8x25s to

the 18x50s - work on the same principle: a computer detects movement and alters

the shape of a special flexible optical element to compensate and cancel the

jiggling your hands induce.

These

new 32mm models have a different system derived from Canon’s cameras

lenses that features two modes: a regular I.S. that permits easy panning and a

‘Power I.S.’ that attempts to eliminate all movement from the view.

It

seems that this new system works by changing the offset between lens elements,

rather than a by distorting a single flexible element. This would explain both

the chunky body and the excessive number of elements Canon quote for the

objectives (seven, see above).

Quite

how the standard I.S. mode differs from the ‘Power I.S.’ I

don’t know, but interestingly these make a muffled clonking sound from

inside when moved about, which the older models don’t.

I

expected that the new lens-offset system would alter the wavefront less than a

distorting element, so was hoping for enhanced optical performance from these

(though the ISIII version of the original system, found in the 12x36s, is

excellent).

Accessories

These 12x32s have a semi-rigid case that’s both

classier and more protective than the 12x36s’ basic pouch. With twin zips

and a flap, it works as a stay-on case when you’re carrying – like

the 10x42s’ only without the half leather. However, the strap is the same

thin, unpadded one as the 12x36s’.

Canon thoughtfully include a pair of AA batteries to get you

started.

In Use – Daytime

Ergonomics and Handling

These 12x32s are light compared to the 15x50s and 18x50s, but

heavier than the 12x36s. They have fatter barrels than the 12x36s too, making

the focuser a stretch with my smallish hands.

The focuser has no backlash or variation in focus point when

reversing direction, but I found it slightly spongy in operation. Best focus is

a real point, though, and the focuser is precise enough to make finding it

easy.

The right-eyepiece dioptre adjustment is standard for Canon

and a bit basic, but smooth and precise enough.

Eyepiece comfort is poor. The eye relief isn’t enough

to allow you to see more than maybe half the field with specs on, but specs off

and there’s only sufficient with the caps rolled down anyway. The

eyepieces are wide too, which means they’d squash my nose if I

didn’t rest them on my eye sockets.

Image Stabilisation

The new dual-mode stabilisation has two buttons instead of

the usual one.

The front ‘stabiliser’ button allows smooth panning,

whilst the back ‘power stabiliser’ button tries to

‘glue’ the image and resist any movement, as if it were a

telescope.

I found the front button gives a fluid, natural view with

smooth and seamless panning – better in this regard than the old

12x36s’ I.S. However, whilst the power stabiliser does anchor the view it

also causes jitter and jerky panning. Overall, the combination is more complex

to use, but a bit better than the 12x36s’.

Activating either I.S. mode causes a loud click, but

it’s silent in operation.

Compared with the 12x36s, the ergonomics are worse. The 12x32s’

twin buttons are a different shape (one convex, the other concave) and texture

from each other and one has a small bump in the armour to distinguish it. But

they are smaller than the older model’s and you won’t tell them

apart with gloves on.

One big improvement over the 12x36s is you can keep the

stabilisation on by giving either button a quick push. Then you can change your

grip or operate the focuser no problem.

The View

The view is basically very good – sharp and detailed. The

two-mode stay-on I.S. does allow smooth, natural panning in normal mode. Optical

quality, as usual with Canon is very high in both barrels and focus suitably

snappy.

Resolution is very high with the I.S. enabled. This is

typical of stabilised binoculars. I can see details I just can’t with the

unstabilised EL 12x50s. I happen on a buzzard in the

woods, preening on a branch 200m away. He flies off before I’m in normal

bino’ range, but I’m still able to view him in close-up detail with

the power stabiliser on.

So there are some great things about the view, some less so. The

field of view is the same as the 12x36s’ at 5° but a little narrow compared with modern 12x birding binoculars.

However, wearing specs you’ll be lucky to see more than ~3° due to the tight ER.

The

other main problem is false colour (see below), which is bad enough to be

intrusive in high-contrast situations. Watching

a Red Kite soar, twisting his forked tail about to manoeuvre, that russet tail

was marred by false colour fringing.

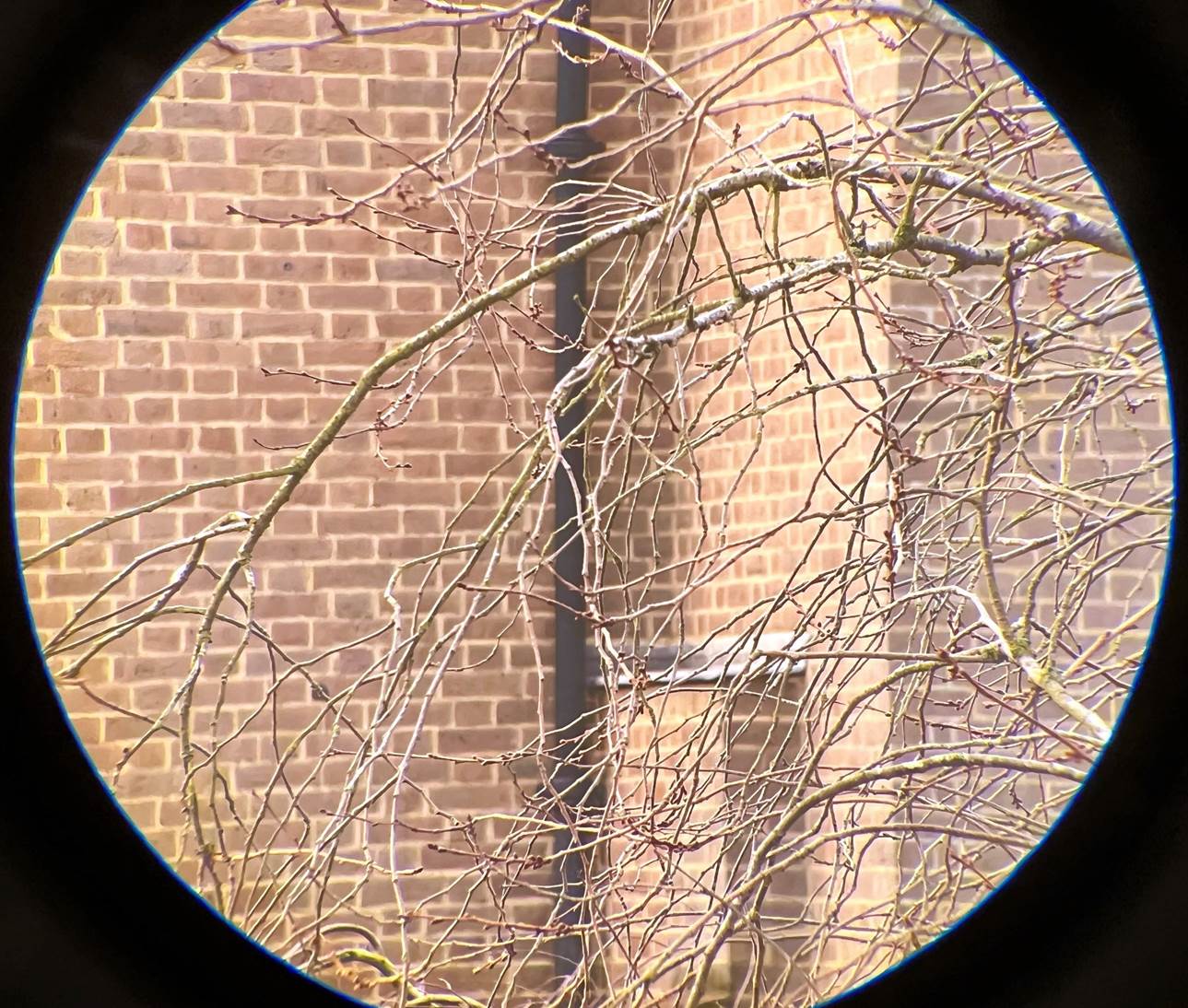

Looking

at a pigeon in a tree a few hundred metres away, there’s noticeably more

false colour fringing the branches than with the 12x36s and it’s more

sensitive to eye position. It gives the view a slightly warm tint too.

That false

colour is very apparent compared with Swarovski’s well-corrected 12x50

ELs.

Flat field?

The view

is sharp to the edge, with very just a little distortion and minimal curvature.

This is something Canon do well, almost too well for birding as the barrel

effect when panning is noticeable.

Chromatic Aberration

As I

noted, false colour is a problem with these. Watching birds in trees,

everything is rimmed with purple or green. That false colour comes mostly from

the eyepieces and you can mitigate it by careful eye positioning.

But some

false colour is also generated by the objectives, obvious when focusing though.

That’s despite the claimed ‘UD’ element, despite the moving-objective

focusing and porro prisms, all of which usually help quell chromatic

aberration.

The

false colour seems to manifest as a slight yellow cast. Photographing the view

seemed to magnify this effect in every image – see below.

Once again,

I just can’t understand why a new model in the ~£1000 price bracket,

with a modest magnification and claimed UD glass, doesn’t fix this old

bino’ issue.

In Use – Dusk

Another questionable feature is the 32mm objectives. This

seems to be a thing with stabilised binoculars (Fuji’s latest are 28mm

giving the 16x model an exit pupil of just 1.75mm) – perhaps it has

something to do with the stabiliser internals?

In this case the view is bright in full daylight, but

performance falls rapidly at dusk like any other 32mm. Yes, the stabilised view

makes up for lack of aperture to some degree, but not enough. The 12x36s, which

gather 27% more light, do work a little better at dusk.

In Use – The Night Sky

As for

the 14x32 model, the drawbacks of the 12x32s by day turn out to be a non-issue for

astronomy: stabilisation makes up for lack of aperture more than you expect and

you discover how much the shakes detract from both limiting magnitude and

resolution. I compared these directly with the EL 12x50s which do go deeper, but

not to the degree you might think.

Viewing

a star field confirms that the field is very flat, with only the merest trace

of astigmatism at the very edge and almost no curvature: stars remain stars all

the way across – a great feature for astronomy.

There is

no nasty flare and only very faint ghosts, even on a brilliant full Moon.

Meanwhile, the slightly vague focuser isn’t a problem – set it once

and leave it. The lack of eye relief, as is often the case, is less troublesome

in the dark too. Their relatively light weight makes them comfy to use over a

long observing session.

The

final advantage is the two-mode stabilisation, which is much more functional at

night – use the basic I.S. to pan about searching for things, then the ‘Power

I.S.’ for the best static view.

The older

12x36s leave in long slow movements, whereas the 12x32s can give a completely

static ‘telescopic’ view on Power I.S. I didn’t find this

very useful by day, but for astronomy it does increase resolution if

there’s nothing to rest on.

The Moon

As with

the 12x36s, the amount of detail you can see on the Moon is surprising for just

12x.

Compared

with unstabilised 12x50s, resolution is remarkable. Swarovski’s 12x50 ELs give a great

lunar view, but it seems typical of binoculars: just the main landmarks - the

maria, brightest rays and biggest craters. The stable view from the 12x32s

reveals much more – lots of individual craters and rays, mountains in the

maria, that you missed.

As I

noted, there is no flare or spiking on the Moon, but there is some false colour

– proper green and purple on opposite sides of the limb – but it

doesn’t detract from the view the way it does by day.

Planets

Jupiter

showed a clean disk surrounded by its Galilean moons, but no disk detail as

always for prismatic systems. Bright Mars was intensely orange with no spikes

or flare.

Deep Sky

The

12x32s give stars both very small and intensely bright, colours strong. Why is

this? It’s typical of high optical quality and also of porro-prisms, but

I wonder if the new stabilisation system helps too.

The

field may be narrow by modern standards, but there’s still plenty of

width to fit the whole of Orion’s sword or belt in with room to spare and

with all the stars sharp. Even in bright Moonlight, the core of the Great

Nebula is visible among a mass of icing-sugar stars.

The

Pleiades look beautiful, even in strong Moonlight: dazzling blue-white

pinpoints of light embedded in a diamond dust of fainter stars.

I was

surprised to find the Ring Nebula, but doing so required averted vision, a

trick you’d need to acquire to get the best out of these for deep sky. It

was a similar story for (relatively) fainter clusters, like M37 in Auriga.

I’m

not a fan of these 12x32s by day, but they perform very well for astronomy,

surprisingly so for a 32mm aperture.

Canon 12x32 IS vs Canon

12x36 ISIII

I’ve compared the 12x32s with the older 12x36 model

throughout this review. Let’s summarise:

·

The

12x32s have more (too much) false colour, from the eyepieces and objectives

·

The

12x32s have smoother, more seemless panning on

regular I.S.

·

Power

Stabilisation in the 12x32s has more artefacts – jitter, focus shift and

jerky panning – but it does give a super-stable view

·

The

12x32s’ Spectra coatings are better than the 12x36s’

·

Stabilisation

in the 12x32s is noisier to activate

·

The

12x32s have less eye relief and are not pleasant to use with your spec’s

on

·

The

12x32s had a slight yellow cast to the view, maybe due to all that false colour

·

The

12x36s are lighter and slimmer, so easier to hold

·

The

12x36s work better at dusk due to 27% more light gathering

·

The

focuser on the 12x36s is more fluid and less spongy

·

The

12x36s I.S. button is larger, easier to push, but the click-to-stay-on feature

of the 12x32s is so much more convenient

·

The

12x36s are significantly cheaper

Overall I much prefer the 12x36s, but the 12x32s’

dual-mode stabilisation does offer some advantages, including smoother and more

seamless panning in regular I.S. mode.

Summary

In some ways the 12x32s are a good

binocular, with a sharp bright view, lots of resolution and a flat field. The

regular stabilisation is smoother and pans more naturally than the

12x36s’. Optical and mechanical quality is generally very high. But they

also have a lot of drawbacks, at least for daytime use:

· The biggest

problem is too much false colour, mostly from the eyepieces, that also gives

the view a slight yellow cast in some circumstances

· The power stabilisation

button anchors the view like a scope, but with lots of jitter and jerky panning

· Eye relief

is much too little for use with glasses, so little that the folding eyecups are

redundant

However,

just as for the 14x32s, they are transformed at night. For astronomy the

downsides aren’t as important, but super-sharp stars, a very

well-corrected field and steady stabilisation count in their favour.

Overall,

though, these underperformed the old 12x36s and won’t replace them as my

travel binoculars, despite some real benefits from the new stabilisation.

For most things I would recommend the 12x36s instead of these

12x32s, but they did perform well for astronomy and their dual-mode

stabilisation is a useful feature.

You can buy

Canon’s 12x32 Binos from Amazon here and give ScopeViews a bit of commission towards new content!