Canon’s 18x50s are their most

powerful image-stabilised binoculars and are widely used for astronomy. But do

they really show you more than the latest conventional big-eye models from

premium brands?

Canon 18x50 I.S. Review

High power image stabilising bino’s have a compelling

use case for astronomers, but most high-powered I.S. models are really too

small for astronomy. Canon’s own new 14x32s join similar offerings from Fujinon and Nikon in this regard: right power, wrong

objective size. Decades on, Canon’s 15x50s and 18x50s are the only

stabilised bino’s with astronomy-sized objectives (Zeiss’

ridiculously expensive low-tech 20x60s aside).

When first I tried a pair of Canon’s 18x50s I found

them of high optical quality, but compromised in terms of the image stabiliser,

which produced too many distracting effects for my liking. At the time I

assumed everyone would start making high-power image stabilised binoculars and

I could soon pick and choose. A decade later it’s clear that’s just

not going to happen.

Meanwhile, I discovered that Canon’s 12x36s have been

quietly revamped to create an excellent astronomy bino’. So I thought

I’d give the 18x50s a second look (and a thorough review on the night

sky).

At A

Glance

|

Magnification |

18x |

|

Objective

Size |

50mm |

|

Eye Relief |

15mm

claimed |

|

Actual

Field of View |

3.7° |

|

Apparent

field of view |

60.3° |

|

Close

focus |

~4m |

|

Transmissivity |

90%

estimated |

|

Length |

193mm |

|

Weight |

1180g (excl batteries) |

Data from

Canon Ireland.

What’s in the Box?

As usual with non-European brands, Canons – even

expensive ones like these - have a basic box:

Design and Build

The Canon I.S.

range, that even they describe as ‘broad’, now (early 2021) has no

less than five different lines, though all share a similar design and look:

· Large,

high-power binoculars of semi-waterproof design, with ED lenses: 15x50 and

these 18x50s

· A new line

of 32mm models featuring a different type of I.S. derived from their camera

lenses, including a 10x32, 12x32 and a 14x32 (see below)

· An

older line including 8x25, 10x30 and 12x36, which share a similar

non-waterproof design, are light weight and fairly cheap. The 12x36s are

a Scope Views Best Buy for astronomy

· Premium

10x42s which are fully waterproof, have special red-ring lenses and are mainly

aimed at birders

· Recent

small and light-weight ‘pocket’ binoculars in 8x20 and 10x20 sizes

Two smaller high-powered Canon I.S. models – 14x32 and

12x36.

Body and Ergonomics

The need to house the I.S. electronics mean these don’t

have a normal binocular body. There is no hinge – the body is just a

solid plastic ovoid with thin, smooth armour. The result is that they look like

consumer electronics, with a button on top and a battery compartment

underneath.

Even if they remind me a bit of an old Sony Walkman, both

external and internal build quality is very high, much like my Canon DSLR in

fact.

At almost 1200g, these are heavy compared to the smaller

models, though - almost twice the weight of the basic 10x30s.

Canon claim waterproofing, but given the potential for water

ingress through the battery compartment and button, these won’t be

submersion-proof like the best roof-prism birding bino’s. You should be

able to use them safely in the rain, though.

Unlike most binoculars, the non-hinged body allows these to

avoid a tripod adapter: there is a standard ¼-20 thread underneath for

attachment to a photo tripod.

Focuser

The focuser is light, precise and free of any kind of image

shift or backlash; as good as the very best in my opinion. It’s not

super-fast, but for the precision needed with optics this sharp, and at this

magnification with a shallow field depth, that’s not a bad thing. From

close-focus of about four metres to infinity is a bit over one turn. There is

plenty of focus beyond infinity, to accommodate different peoples’

eyesight, too.

In order to make these waterproof, the focusing mechanism is

(unusually for porros) internal – the focuser

moves the objectives in and out behind a sealed optical window.

You adjust dioptre (the difference in focus between your

eyes) by the traditional method: twisting the right-hand eyepiece to focus it

independently. In this case, it works smoothly and precisely with just the

right weight (on many binoculars it’s much too stiff).

Optics - Prisms

These are porro-prism binoculars (though they don’t

look like it) – the same optical design as

‘Grandad-bino’s’. But if you think that’s a bad thing,

it’s not. In general, porro prisms give slightly higher performance than

roof prisms because they transmit more light since they don’t need mirror

coatings.

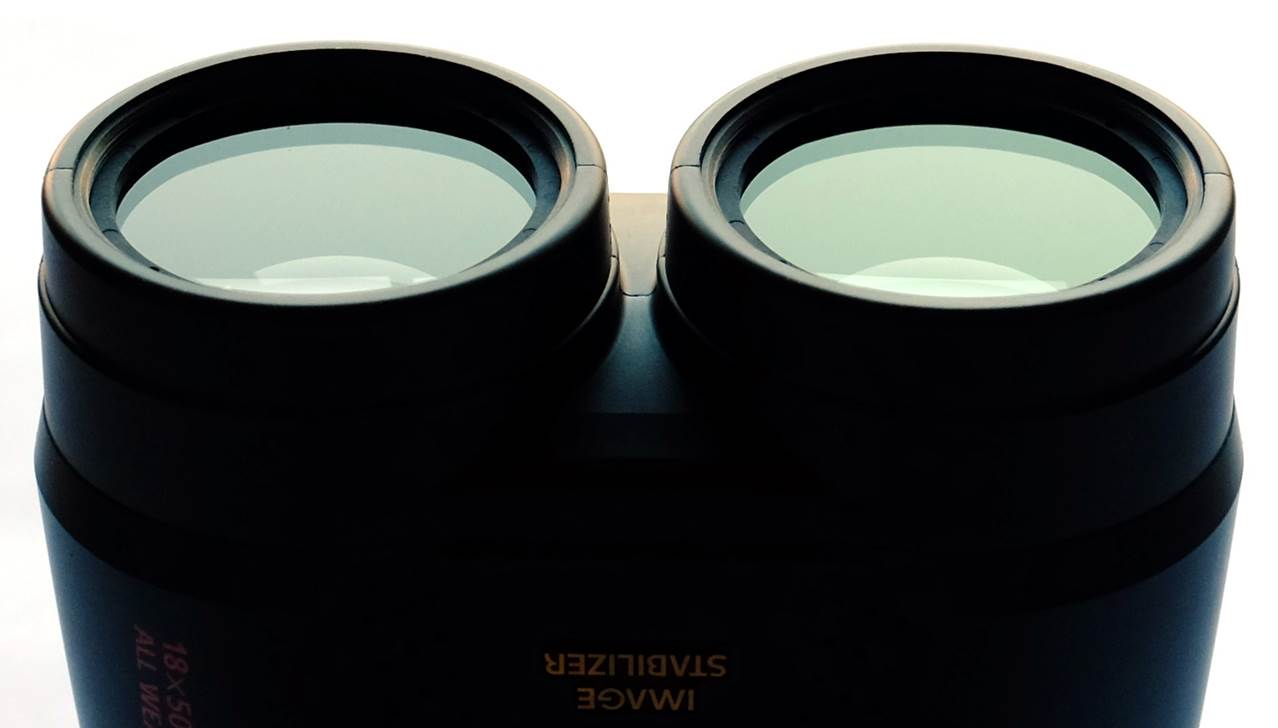

Optics - Objectives

Canon claim that these objectives have a four-element design;

I’m not sure if that includes the optical window they’ve added to

the front for waterproofing.

Unlike the cheaper models, including the 12x36s and even

14x32s, these 18x50s feature objectives containing one element of special dispersion

glass. Canon refer to this as ‘UD’ (ultra-low dispersion). Some

manufacturers use labels like ‘ED’ or ‘SD’ to describe

much the same thing, whilst others confusingly call their binoculars

‘HD’ because those special lenses give a higher definition view.

The point is that one of the lens elements is made of a

special type of glass high in fluorides that gives better resistance to

chromatic aberration (false colour fringing around high contrast parts of the

view). With such a high magnification, this is pretty much essential.

Coatings are purple in hue (not the more neutral tone you get

with high-end German bino’s these days), but they are very dark and of

high-quality. Combined with the inherently lower-loss porro-prism design, these

should give very good light throughput for a bright view.

It’s worth pointing out at this stage that overall

optical quality is very, very high. There is none of the softness you get with

some high-powered binoculars. Canon make a lot of quality optics (including the

objectives for Takahashi telescopes) and that experience shows here. In terms

of sheer optical quality, these give nothing away to the likes of Swarovski,

Zeiss and Nikon.

The insides of the barrels are machined with lots of fine

baffles to kill stray light and prevent flare.

Barrels are

outstandingly well baffled against stray light.

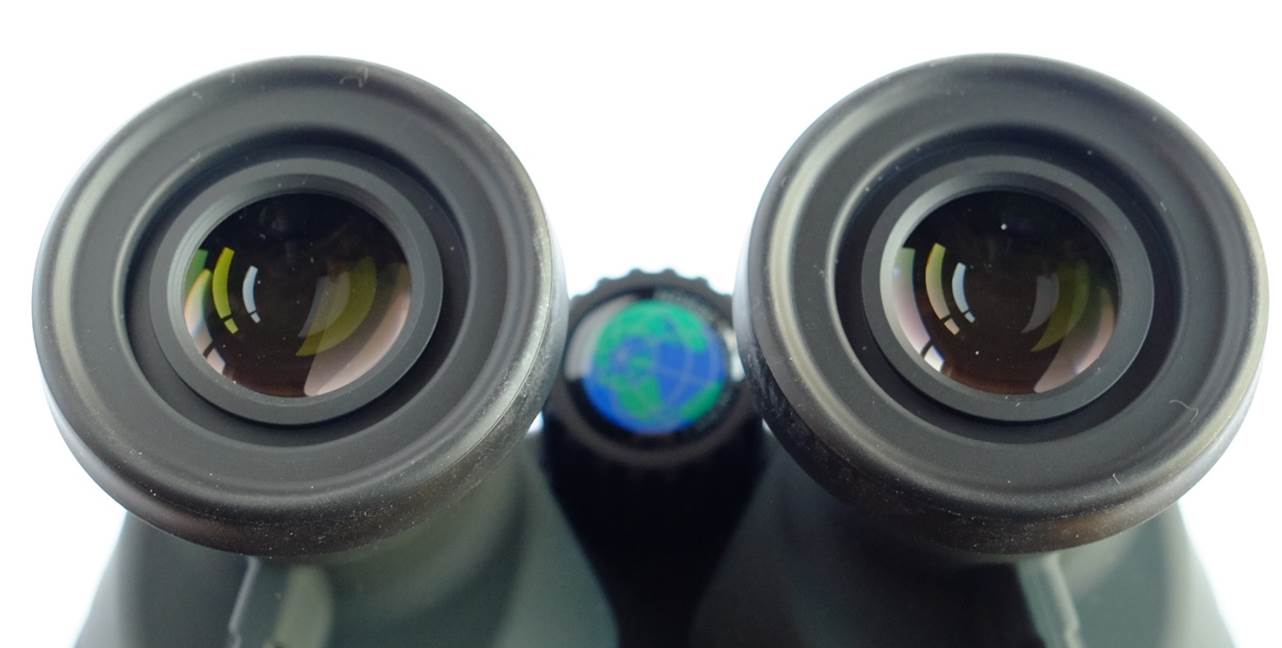

Optics – Eyepieces

The eyepieces are a complex design that Canon state has seven

elements, including a doublet field flattener. That multi-element eyepiece

design delivers a fairly wide (for binoculars) 60° apparent field of view, that

translates to 3.7° true field width. In theory, these

eyepieces also have decent eye relief too (the distance away from the eyepiece

that the image is formed), for comfort with glasses …

Canon claim 15mm of eye relief (exit pupil distance),

measured from the eye lens. But the eye lens is deeply recessed in the eye cup

and so the effective value is more like 10mm. This means a greatly reduced field with glasses on and just isn’t

up to industry-leading standards these days.

Another problem is inter-pupillary distance. With no bridge,

these have moveable eyepieces to accommodate different inter-pupillary

distances. That’s fine, in theory, but the big eyepieces and cups will

squeeze your nose if your IPD is small, like mine.

Most premium binoculars these days have twist-adjustable eye

cups with several settings. These have the old-fashioned fold-down rubber eye

cups, that are much less adjustable and will probably eventually perish and

split at the fold point. The eye cups are sticky rubber and are magnets for

dust. They are, however, easy to fold and work well, unlike some.

Optics – Image Stabiliser

The

biggest problem with high-powered binoculars is that the extra magnification

amplifies your shakes as well, blurring the view and making it harder to see

fine details. These can be used without stabilisation, just like normal

binoculars, though 18x really does magnify hand-held shakes a lot. So,

you’ll mostly use them by activating their image stabilising function.

The

image stabilisation employs a microprocessor to detect movements and then alter

what Canon describe as a ’vari-angle

prism’ to counteract them in real time. Most of Canon’s I.S.

bino’s work this way, but not all. Canon’s most recent models, like

the 14x32s, have a dual-I.S. system that changes the offset between lenses

instead of the flexible prism. This new system is derived from their cameras

and is supposed to be higher fidelity, though my review of the 14x32s

didn’t convince me it was significantly better.

Other

manufacturers have image stabilising binoculars which use different systems,

like gyros to simply resist the shaking, or with gimbled prisms.

Like

other Canon stabilised binoculars, you activate the I.S. system on these 18x50s

by pushing a button. The button is quite deeply recessed and takes a firm push,

but an audible click and a green light confirm the I.S. is active. Alternatively, you can give it a

lighter push, in which case the I.S. is active only until you release the

button again.

The first pair of these I tried, many years back, had pretty nasty

I.S. with lots of unpleasant artefacts: the focus point faded in and out;

colours jazzed; panning was jerky. These are much better; on first look, the

I.S. seems virtually flawless: the image just steadies very positively and

effectively. There is little noise and panning works fine too.

However, there are still downsides to the I.S. on these,

Canon’s most powerful model, that lower-powered ones like the 12x36s

avoid:

1)

The

I.S. can take quite a few seconds to really settle and deliver full resolution.

Until then, one or both barrels can be blurred as if defocussed slightly,

leaving you twiddling the focuser in frustration. Meanwhile, it’s as if

the optics are poor (they’re not, the effect wears off after a while if

you hold them reasonably steady). This initial defocus is very noticeable on

the Moon, stars and planets, but on daytime landscapes, too.

2)

Too

much shakes can re-introduce that blurring, until you and the system settle

again. This means getting and retaining a perfect view for long periods can be

difficult.

3)

In

use, the I.S. will occasionally make a clicking noise, or suddenly jerk the

view about a bit, if you stress it with too much shaking.

Overall, the I.S. works well though.

Hold them steady and you are (eventually) rewarded with an impressively sharp

and stable view; rest on something and the view is telescope-steady.

Accessories

The 18x50s have a plain Cordura soft case, a basic strap with

quite thin webbing and press-on eyepiece caps only. The case is annoying

because the catch looks particularly fragile. Binoculars this costly deserve

better.

In Use – Daytime

Ergonomics and Handling

Handling is the only area where these are noticeably worse

than most current premium binoculars. That fat, bridgeless body is harder to

hold than nicely sculpted barrels and the armour feels thin and less grippy

than the best. That said, the focuser is superb and the dioptre adjustment

simple but effective.

Weight is similar to most 50mm binoculars, although they do

get tiring to hold up after a while when compared to lightweight 10x42s, for

example. They do feel much heavier than some of the smaller models, like the

12x36s and 14x32s.

It’s the eyepieces that are the main comfort problem.

For me they are not really comfortable with my specs off and balanced on my

nose (or squeezing it), but they don’t have enough eye relief to show

much more than about half the field with glasses on.

In my opinion, these are not an attractive-looking pair of

binoculars. If you want a certain sartorial panache to your bino’s, then

you’ll need to look elsewhere (perhaps Leica’s beautiful

leather-armoured models).

The View

Considering their high magnification, these give a very

bright, sharp, high-contrast daytime view. You often do need to wait for a few seconds

for the view to stabilise fully and reach maximum sharpness after you engage

I.S., though. The field is wide and focus snap absolute, though the depth of

field is very shallow (something to be expected with a high magnification) and

so you do need to use the focuser a lot.

The high magnification, superb optics

and stabilisation mean that these 18x50s resolve more than almost any other

hand-held binoculars.

That high power and steady view allow you to identify birds

at extreme range. I managed to ID a Kestrel soaring a kilometre or more off,

just a speck with the naked eye. I watched a pair of Jackdaws mobbing a Buzzard

hundreds of metres away. They would be a valuable addition to a birder’s

kit-bag, for when a scope isn’t possible or available.

The 18x50s’ capabilities don’t stop with birding

either. I tracked a Hawk fighter aircraft headed out over the Lake District

from miles away, an extreme range to be able to make an ID, much further than

any other hand held would have allowed. These would work very well for plane

spotters.

For other kinds of daytime spotting, marine use, or nature

viewing, these again show you more than any normal hand-held binoculars:

looking across the bay to Morecambe, eight miles away, I could see individual

houses, cars and trees, that are normally just vague impressions with other

binoculars.

Flat field?

These Canons are advertised as having field flatteners and

indeed the field is very flat for binoculars, one of the very flattest I have

tested - largely free from astigmatism and curvature and with just a little

distortion. Even the field edge is completely usable.

Chromatic Aberration

When discussing chromatic aberration, we have to consider

that 18x is a very high magnification for binoculars (false colour worsens

dramatically at higher powers, given the same optical design). So, yes, there

is false colour: you can easily see it on silhouetted birds or branches,

especially when focusing through - a purple tinge one side of focus, green the

other.

In general use, false colour isn’t a problem, though.

Watching my local Jackdaws in silhouette against a dusk sky, huddling in pairs

and settling into their high branches for the night, is particularly easy with

these, slight colour fringing notwithstanding.

Like most high-power designs, these suffer from an increase

in chromatic aberration near the field edge, but it’s not as bad as some

and rarely intrusive.

In Use – Dusk

These

penetrate dusk shadows well, due to their high magnification, steady view and

bright porro-prism optics.

In Use – The Night Sky

Canon (unusually) list astronomy as one of the possible uses

for these 18x50s, so I will spend some time reviewing these on the night sky

– object by object – but I will start with some general

observations.

Once the I.S. has settled down, Vega yields nice round,

concentric rings either side of focus – a sign of excellent binocular

optics (even though the power is a bit low for a ‘proper’ star

test).

Stars remain points right to the field stop. These

don’t have a significantly curved focal surface or much off-axis

astigmatism (that turns stars into blobs or lines, respectively), unlike many

bino’s. That doublet field flattener does a good job of making these one

of the flattest-field binoculars of all, a great feature for astronomy.

The field of view is good for the high magnification, at 3.7° true. It’s enough to encompass more or less any region

of sky you might want to view. Whilst the area left by the vignetting you get

wearing glasses is smaller, it’s not as much of a problem at night and

still leaves enough sky area to fit in Orion’s sword region, for example.

Nonetheless, these don’t give the gorgeously wide star fields that fine

10x50s do.

There is some faint ghosting with a bright light in the field, but that careful baffling

means that working around bright

lights is never a problem – good news for urban users.

One trick I learnt with these is to look for things by

panning slowly with the I.S. enabled

– the steadier view makes finding fainter objects easier.

The Moon

One day past full and pressing the magic button yields a host

of craters – including dark-floored Endymion and Mare Humboldtianum

behind it - along the terminator in superb, sharp detail … eventually. At

first, though, the view is slightly soft and fuzzy. I have to wait for perhaps

twenty seconds for the I.S. to settle down and the view to sharpen fully.

Thereafter, a final tweak of the focuser (the sweet spot is very small)

delivers a view like mounted binoculars.

On day four of the next lunar cycle, elbows resting on the

roof of my car for a bit of extra support, I again get a telescope-like view

with all the major features easy to pick out. The bigger craters, like

Cleomedes, Langrenus and Petavius

are easy, but I can make out smaller ones too - Picard in Mare Criseum and nearby Proclus with its bright rays; Stevinus, Snellius and Geminus on the terminator, floors full of

black shadow. The view is perfectly sharp and full of contrast and detail, with

only a little false colour around the bright Lunar limb to complain about.

I would buy a pair of these Canon 18x50s if I lived in the

suburbs with nowhere to set up a scope, even if only to enjoy the Moon. Once

settled, these give Lunar views much more like a telescope than any other

hand-held binoculars. Most of the features in my ‘Photographic Atlas of

the Moon’ are within its grasp and that steady view makes the Moon really

explorable.

Venus

Venus in a dusk sky showed a little flare until the I.S. had

settled for perhaps 20-30s, then almost none. Venus’s brilliant white

gibbous orb, at 19” across, was then very easy to make out, by far the

best view of it I have had with binoculars. This is impressive – more

than a few spotting scopes struggle with Venus.

Jupiter

With the usual caveat about waiting for the I.S. to settle

down, the view of Jupiter was outstanding for binoculars. The planet appeared

as a perfect disk, an unexpectedly large one due to the high magnification.

There is no spiking or smearing at all. In a brightening dawn sky that lowers

the contrast a bit, I could even make out a hint of the equatorial belts, a

rare ability in binoculars. Jupiter’s Galilean moons were super easy to

track with these.

Mars

Of course, these aren’t about to show you albedo

marking on Mars, but even six months after opposition, when it’s very

small, Mars is still obviously a planet – bigger than the tight Airy disk

of a similarly bright star.

Deep Sky

For small DSOs, the Canon 18x50s are a winner. The Ring

Nebula (M57) is easier to find than with any other hand-held binoculars

I’ve tried. Similarly, the Dumbbell isn’t as bright as through

big-eye 56mm binoculars (which gather 25% more light), but shape and definition

is outstanding, really picked out from the background by the steadying effect

of the I.S. The Crab Nebula (M1) is again easier to pick out than usual and

shows its shape better than in any lower-powered hand-held binoculars. Bode’s

Nebula, big and clear through the 18x50s, also shows more of the shape and

character of its two constituent galaxies. What’s more, the high

magnification supresses sky glow and haze, helping find smaller DSOs.

Globular Clusters are easy to find and look good too; M15,

right of star Enif in Pegasus, looked like a properly

fuzzy star, albeit a bit dimmer than through a good 15x56. Smaller, but still

obviously a globular, is M56 between Cygnus and Lyra – quite hard to find

in smaller bino’s but easy with these.

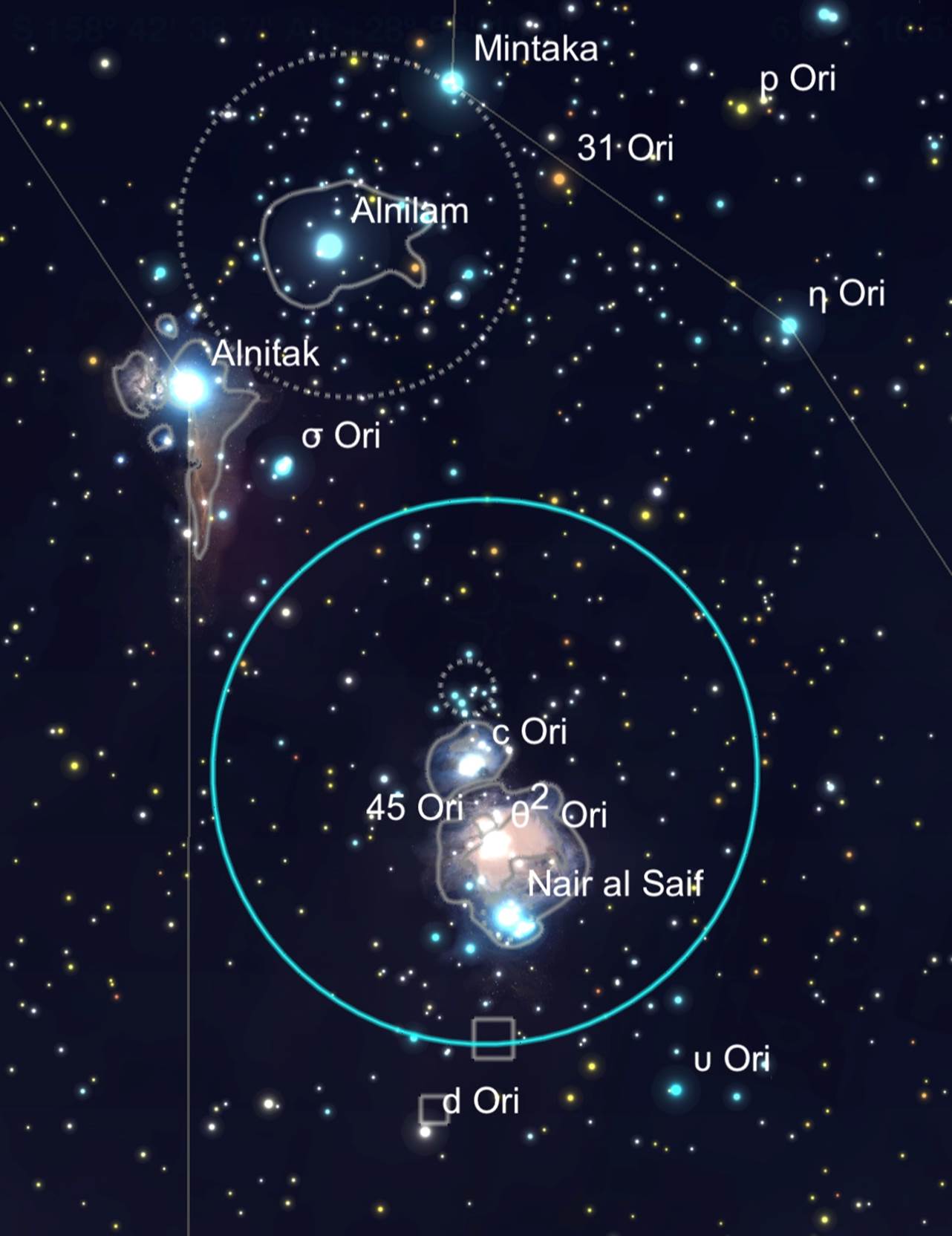

The sword area of Orion, with big and bright M42, looks

‘telescopic’ through the 18x50s, with the four main Trapezium stars

easily resolved. The nebula is big and bright and shows a lot of detail,

especially with averted vision; I can see hints of whorls and the

‘arms’ and central ‘spike’ of nebulosity spreading a

long way into space. Still, the smaller aperture means I can’t see hints

of colour as well as with 15x56s under dark skies.

The news is also positive for open clusters. The Starfish and

Pinwheel clusters in Auriga aren’t as bright as through 15x56s, but show

all their bright constituent stars and their very recognisable shapes in a way

lower powers and non-I.S. just don’t permit. The Double Cluster similarly

isn’t as bright as through 15x56s, but it’s easier to see

individual stars within it.

On the downside, I did notice that fainter galaxies are a bit

harder to find than through 15x56s, whilst M31 is just too big for the smaller

field of these.

Overall, the flat field, high

magnification and I.S. make these a superb astronomy tool that excels on the

Moon and small DSOs. But lack of aperture means a bit less reach than fine

15x56s and nebulosity sometimes looks less bright and detailed as a result.

Canon 18x50s’ 3.7° field of

view on Orion.

Satellites

One possible interesting use for these is hunting and

watching satellites. They have the useful property of telescope-like

resolution, with binoculars’ ability to pick up and track fast-moving

objects. I watched a bright satellite (perhaps some Cosmos flavour) cross the

sky, sweeping to follow it with the I.S. (no pun intended) engaged, and I could

make out its cross-shape, formed by the fuselage and solar panels.

Testing the

Canon 18x50s.

Canon 18x50 vs Zeiss 15x56 Conquest

HD

The discounted price of these binoculars is very similar.

Both offer outstanding value for hand-held astronomy and are obvious

competitors. So how does the German engineering and bigger aperture of the

Zeiss stack up against the higher power and image stabiliser of the Canons?

· Weight is similar, but the Canons are

more compact

· Optical quality is similar

· Chromatic aberration levels are

similar

· The Zeiss Conquests have more eye

relief – a big factor if you wear glasses

· The Zeiss have a wider field, but the

Canons’ is more perfectly flat

· The Zeiss give a wider field for

panning through star fields

·

The higher magnification and I.S. make the Canons much better for the

Moon and smaller DSOs, able to resolve detail no normal hand-helds can

That last is the killer app here. If you live under urban or

suburban skies with nowhere to regularly setup a telescope, or if you value

super quick-looks between the clouds, get the Canons.

Summary

The first thing to say is that image stabilisation is no

gimmick and works well, delivering way higher resolution than any normal hand-held

binoculars can, especially at this high magnification. The basic optics are

first rate too, giving a flat, sharp, bright and very wide field. No issue with

the focuser either, it’s smooth and precise.

Make no mistake, the resolution of these is a big deal. For

very long-range birding, exploring the Moon, or perhaps checking out the secret

aircraft on the Tonopah Test Range in Nevada from that hill south of Highway 6

(sorry, Mr CIA Man, Sir, I was just kidding), these outperform everything else:

no conventional binoculars are going to reveal as much without a tripod.

So, the image stabiliser really works, but it does take a

long time to settle and can occasionally make the view jerk around or

temporarily blur whilst in use.

There are other issues, too. The biggest is with the

eyepieces. There isn’t enough eye relief to see anything like the whole

view with glasses and the eye cups are the old-fashioned roll-down type. More

problematic for some people is that the eyepieces are too fat and pinch your

nose, if you have a small inter-pupillary distance, like me; you can get around

this by folding the eye-cups down and kind of resting them on your nose, but

it’s not ideal. Another small issue is that the depth of field is very

shallow – you have to re-focus a lot when you pan around during the day.

Though the build quality is high, these are a bit plasticky

compared to a fine conventional binocular of similar price. You should also

consider that these are essentially a piece of consumer electronics -

they’re not an heirloom the way those Swarovskis,

Zeiss or Leicas could be.

But here’s the thing: if you need the highest resolution in a hand-held binocular – for

birding, spotting or astronomy – these deliver like nothing else.

Do you really need a scope, but don’t have the time or

space? You just found the best solution currently available. Canon’s

18x50s are very highly recommended, if you can live with their downsides.

You can buy the similar 15x50IS Binos from Amazon here and give ScopeViews a bit of commission towards new content!