Celestron C5 XLT Review

I really try to remain impartial when reviewing gear. But

it’s no secret that until recently I was pretty down on SCTs. The orange-tube

C8 I bought new in 1981 had never been much good, optically or mechanically. A

friend’s recent Meade 8” had been similarly poor, as had the 12” Meade I used

on a university course. To be honest I thought it was the basic design and

concept – something to do with a biggish central obstruction and fast primary

with moving-mirror focusing. I was wrong.

The problem with the SCTs I had tried, I realised, wasn’t the

fundamental design, but that old quality thing again. The recent, Chinese-made

C8 XLT I reviewed in late 2013 had the same large obstruction, fast primary and

moving-mirror focus as those other SCTs; it was even very slightly out of

collimation. But nonetheless it was an excellent telescope, one I would seriously

consider owning myself: it gave fantastic lunar and planetary views for its

size and cost.

Over the last few years I have been trying out as many

portable lunar and planetary scopes as I can. Given my positive experience with

a modern C8, I was keen to try the smallest SCT Celestron

make, the C5. The C5 has been around since the late Seventies in various forms

and on various fork and equatorial mounts, but here I’m testing the basic OTA

with the latest XLT coatings.

At

A Glance

|

Telescope |

Celestron C5XLT OTA |

|

Aperture |

127mm |

|

Focal

Length |

1250mm |

|

Focal

Ratio |

F 9.8 |

|

Central

Obstruction (incl. holder/baffle) |

48mm

(37.8%) |

|

Length |

280mm w/o

visual back and obj. cap (330 with). |

|

Weight |

~2.7 Kg |

What’s

in the Box?

The C5 OTA was delivered packed in its

(standard) carry case.

Design

and Build

Optics

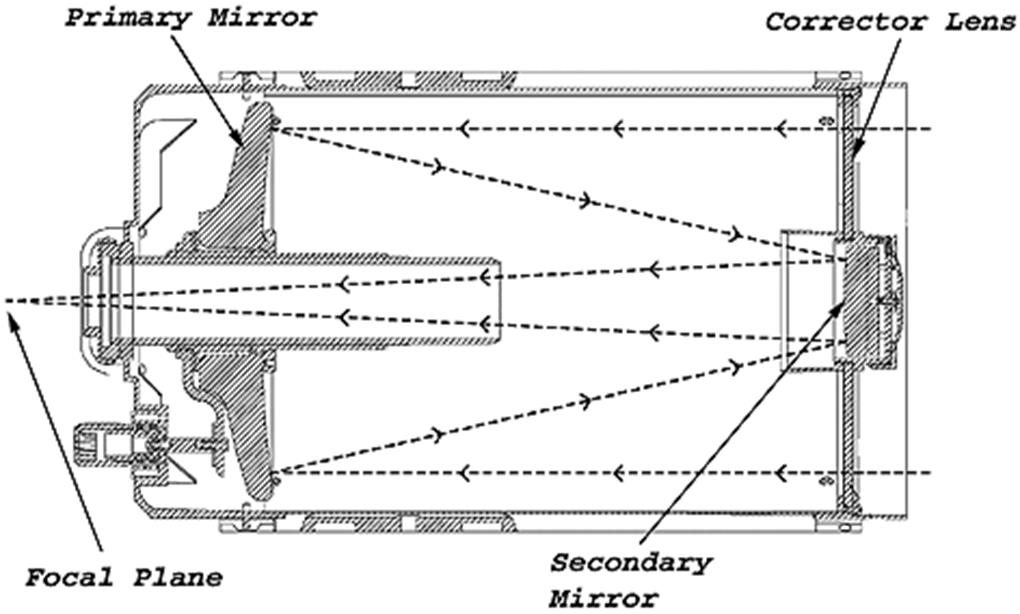

As I’m sure you know, the C5 is a

Schmidt-Cassegrain Telescope (SCT), a type that belongs to a class of

telescopes that uses both refractive and reflective elements in combination – a

catadioptric. In this case, the main mirror focuses onto a secondary which in

turn reflects the light back through a hole in the primary, so it is indeed

a variant on the Cassegrain; a corrector plate at the front supports

the secondary mirror and corrects aberrations in the primary optics.

The SCT design has advantages in terms

of compactness and light weight. The corrector is thinner than that in a Maksutov, so the C5 is lighter and more back-heavy than the

Skywatcher Skymax-127, for example. It is shorter

too. However, that compactness requires steeply curved optical surfaces – the

primary mirror is F2; compare that with the F3 primary on a Takahashi Mewlon Cassegrain.

Such a fast mirror can be hard to make well and close tolerances are

required if performance is to be good. That thin corrector plate is made of

float glass too, same as your windows, which can have inhomogeneities.

Another disadvantage of the design is

the large central obstruction. In this case the secondary mirror and housing

are 48mm across, equating to almost 38% of the width. A 38% obstruction is at

or beyond the very top end of what is acceptable for visual use and is the

largest I’ve ever reviewed; 33% is generally accepted as the maximum for a

high-performance system (excepting the large obstructions found in some

astrographs, where it matters less than for visual use). A large obstruction

does reduce contrast, but the main effect in my experience is to worsen

performance in poor seeing.

Like most commercial SCTs, the C5 is an

F10 design. That means it has a 1250mm focal length, which is relatively long

and means the maximum field of view with a 1.25” eyepiece like a 32mm Plossl is 1.2°, but in fact the usable field, due to

off-axis aberrations, will be more like 1.0°.

The baffle tube is just 38mm clear aperture,

so fitting a 2” visual back wouldn’t allow maximum benefit from 2” eyepieces

with the widest field stops. Theoretically you could get about 1.5°, but again

off-axis aberrations will limit the usable field to perhaps 1.25°.

So

the C5 is never going to give you much more than a 1.25° field of view and this

is a disadvantage of this (or any other SCT) compared to a refractor.

One big advantage of a long focal length, though, is that you can get high

powers without using complex, expensive eyepiece designs – Plossls

and Orthoscopics are adequate.

SCT optical configuration, from

celestron.com

C5 Primary and baffle tube seen through

the almost-invisible XLT-coated corrector.

XLT coated corrector plate and 38%

central obstruction.

StarBright XLT

The first (70s and early 80s) C5s had

an un-coated corrector, but this one has proper multi-coatings (as you can see

in the photos). Celestron call this premium coating

technology ‘StarBright XLT’, as distinguished from

the earlier ‘StarBright’ coatings. StarBright XLT employs multi-layer mirror coatings and

multiple layers of magnesium and hafnium fluoride on the corrector plate. Celestron also use a better, more transmissive glass for

the corrector than in previous models. Overall, Celestron

claim 83.5% transmission for the system, up from 72% for the original StarBright coatings.

The C5 is very compact and light weight

for a 5” telescope.

Tube

The tube and castings are completely

different in detail from the original C5, but the overall design remains

much the same with solid metal front and rear castings and an aluminium tube.

Build quality looks more mass-produced than the original C5 and isn’t up to the

standard of the C8: the OTA is fixed together by screws, some of which aren’t

seated all that well. Overall external build-quality is adequate but no more.

A plastic dew-cap is provided, but

unlike the C8 cap this one is a simple push-fit.

Focuser

C5 Focuser, standard 1.25” and visual

back.

Like many Cassegrains,

the C5 focuses internally by moving the main mirror. This has advantages over

an external focuser – it keeps the tube sealed, the eyepiece in one place and

allows lots of focus travel. In many cases, though, it also comes with issues –

notably the tendency to cause the image to move when changing focus direction

(‘image-shift’) and mirror-tilt that can move the sweet spot when you back out

and degrades the image as well. As we will see, this C5 (unlike some earlier

versions) suffers from neither of these issues: the focuser is smooth and

precise.

Mounting

The C5 on test has a Vixen dovetail bar

running the length of the OTA. Mounted on my Vixen GP it needed just the

smallest counterweight to balance it. The dovetail would easily allow the C5 to

mount up on any small equatorial or altaz mount

accepting the Vixen dovetail (an EQ5, Porta etc).

The bottom of the bar has two ¼-20

threads that can be used to mount the C5 on a photo tripod (it would have to be

a hefty one); I used them to fix the OTA to a small Losmandy

clamp which then slotted onto the upside-down dovetail atop the rings of my

permanently mounted large refractor.

C5 Vixen-compatible dovetail with handy

¼-20 threads.

The C5 piggy-backed atop my

TMB175/AP1200.

Accessories

The C5 OTA comes with a

permanently-attached vixen dovetail bar, 1.25” visual back, star diagonal, 6x30

finder and a 25mm eyepiece as standard.

The finder is baffled and multi-coated

and has good eye relief and a bright field; it’s identical to other Synta 6x30 finders. The eyepiece is a nice multi-coated Celestron E-Lux Plossl and the

mirror diagonal looks decent quality too.

The C5 comes with a very useful soft

case that is very well padded with dense ethafoam to

provide lots of bump-protection. The case is light and properly carry-on

portable at 39x29x20 cm. In reality this soft case is going to be a more useful

travel case than most hard cases and really adds to the C5s travel-scope

credentials.

Celestron

C5 carry case – ready to go with you.

In

Use – Daytime

The C5 is sold as a spotter and it does

give excellent daytime views up to 100x and beyond. There is no chromatic

aberration worth noting and sharpness is very good centre field (though not at

the edge). I was able to watch birds in the copse 200m away as if through binos in my own garden.

In daytime, best focus is an absolutely

crisp point and I note that the focuser is very precise and has almost no image

shift; what tiny amount there is remains well damped at all times. Best focus

is also exactly the same focusing out and then back, suggesting mirror tilt is

well controlled.

The C5 makes a great budget long-telephoto

lens and I got some crisp photos of a roosting pigeon about 50m away; a

paparazzo could doubtless make good use of the C5 for getting snaps of A-lister

indiscretions.

All

in all, the C5 makes a very fine high-power spotting scope during the daytime.

Snap of a roosting pigeon through the

C5.

In

Use – Astrophotography

For astrophotography, the C5 suffers

from two problems:

1) Off

axis aberrations: field curvature and coma

2) Arcing

reflections from bright stars just out of view

It might do better with a flattener and

some judicious flocking of the baffle or focuser tube.

Below are an

unprocessed image of the Moon (the best I could manage from about sixty shots)

and a misty single frame of M42 to show those arcs from bright stars outside

the field and the comatic stars towards the field

edge (even on an APS-C sensor).

Moon through C5 XLT – unprocessed image

is a bit soft and worsens off-axis, but overall not bad.

M42 through C5 to show the reflection

arcs caused by bright stars just out of view: 45s Fuji XM-1 APS-C at ISO 3200

In

Use – The Night Sky

General

Observing Notes

Cool-down is slower than a typical

doublet refractor, but not as lengthy as a Maksutov

which has a much thicker corrector plate. Still, slow cool-down limits the C5’s

use as a quick-look telescope.

I noticed

that the C5 view through a lowish power (32mm plossl) was unpleasant due to secondary mirror shadow, especially

on the Moon.

Star

Test

The star test

was excellent: virtually identical either side of focus with good, even

illumination.

The

Moon

As with other

designs that have a large central obstruction, the C5 suffers when seeing is

poor. On a night with a lot of fine turbulence and the Moon just past 1st

quarter, I had the C5 set up next to Takahashi’s little FS-60Q 60mm

apochromatic refractor, with a 13mm Ethos in the C5 and a 6mm Ethos in the

FS-60Q giving roughly 100x magnification in both.

Not only did

the Tak’ cool completely within 15 minutes from a

warm room, it delivered a much steadier (though also much dimmer) view. I also

noted that under those conditions the little refractor actually resolved more

detail, with Rima Huygens and rima Ariadeus more obvious than through the C5. The FS-60Q also

gave a better view of the whole Moon,

due to a flatter field and less off-axis aberrations generally.

Poor seeing affected

the C5 more than my 175mm refractor, even though sensitivity to seeing

generally worsens with aperture. At 100x, the view through the big refractor

shimmered, but the image remained intact and detailed. Meanwhile the C5 was

mushy, the whole image blurred. Blame that big secondary mirror.

In the early

morning, when seeing is usually better here, I finally got some really stable

conditions. The C5 gave a good view at last at 114x with an 11mm Tele Vue Plossl. The Moon was just a

few days past full and I enjoyed picking out craterlets in Mare Criseum and exploring the deeply-shadowed mountains and embayments around its rim and the drowned craters Lick and

Yerkes. Even so, the view wasn’t as crisp and contrasty

as in a small APO and more unfocussed light was washing out from the bright

limb into what should have been black space.

Jupiter

Unfortunately, Jupiter was the only

planet around during the period of my test.

At a magnification of 114x with an 11mm

TV Plossl, Jupiter was just a mushy ball in mediocre

seeing, but in quite good seeing all the main features were easily visible: the

polar hoods with hints of fine banding, the NEB and SEB (obviously), with

darkened and thickened areas and hints of other cloud belts too. I could just

about pick out the GRS when it came into view.

Overall, Jupiter in good seeing looked

similar to a good 60-70mm APO, though perhaps not quite as crisp and contrasty and again with more stray light around the

planet’s limb.

Deep

Sky

Perhaps

surprisingly, visual deep sky is the C5’s forte. That theoretically narrow

field is really plenty wide enough for most things and the off

axis aberrations still leave a decently flat portion almost a degree in

width. Then again, the XLT coatings and big (for a tiny scope) aperture help to

deliver lots of bright stars and better picked out nebulosity than you get in a

small refractor. The high optical quality also helps out here: stars are nicely

pinpoint and brilliant.

Clusters

M35 looked good with pinpoint stars

off-axis until about 80% field width. At low powers on deep sky you don’t get

the unpleasant secondary-shadowing effect you do with the Moon and so 39x with

a 32mm Plossl gives great views of the deep sky

through the C5.

M36, M37 and M38 in Auriga

These clusters are favourites of mine.

The C5 filled them with plenty of stars, and off axis aberrations were confined

towards the field edge, so didn’t spoil them.

The Pleiades

Unfortunately, the C5 suffers from the

same problem as the Sky-Watcher Sykmax-127 Maksutov I

tested earlier this year: bright stars just outside the field of view form arcs

of reflection that intrude a long way into the field, spoiling the view. You

can clearly see this on the image of M42 below. Even so, The Pleiades looked

good through the C5, with bright stars.

M31

The Andromeda galaxy is big, so

shouldn’t work in something like the C5, but actually the whole central section

was nicely bright and picked out from the star fields in our own galaxy and I

could start to make out the big dark lane to one side.

Bode’s

Nebula

The two contrasting galaxies of Bode’s again looked good through the C5. No longer quite

the faint blobs they are in a small refractor, dark skies and averted vision

gave hints of their true shape and structure.

Globular clusters

The C5 is good for globular clusters.

They benefit from the extra light gathering power and don’t tax the narrowish field of view. M15 looked like a bright fuzzy star

at 39x and started to reveal its components at 114x, even under a murky,

pre-Moon-rise sky.

Doubles

Rigel was split, despite extended

plumes of seeing thrown off from the diffraction rings, but I had trouble with

Epsilon Lyrae: blame that sensitivity to seeing

again.

Nebulae

M42 was surprisingly nice, with detail

and even some colour, but those arcing reflections did spoil the view a bit.

Even so, the XLT coatings and the extra aperture gave the C5 an advantage over

a small refractor here.

The Ring Nebula again worked well

through the C5 – floating in a nicely populous star field, its shape was really

obvious at 39x.

Other brighter planetaries,

like The Crab and the Dumbbell, also looked good through the C5, especially if

you are used to the dim views through a small refractor.

Celestron C5 XLT vs Takahashi FS-60Q

In one way this isn’t fair: the

Takahashi is much more expensive. But it’s an interesting comparison of two

valid but different ways to create a super-compact travel scope with eclipse

potential. A list of main comparison points follows:

·

The C5 is actually much shorter and

more compact, but a kilo heavier

·

The FS-60Q will pack just as small

because it takes apart

·

The longer focal length of the C5 means

greater native image scale, but narrower field

·

The C5 gathers a lot more

light so is (a lot) better for most deep sky objects

·

The C5 should have much better

resolution, but this doesn’t work out in practice

·

The FS-60Q cools much more quickly

·

The FS-60Q deals with poor seeing much

better

·

The FS-60Q is much sharper on axis

·

The C5 suffers from off-axis aberrations,

too much so for serious imaging; the FS-60Q has a very well corrected field

across a full-frame sensor

Overall, the Takahashi is much the

better scope unless visual deep sky is your thing.

Summary

Given my good experience with the C8

XLT a year ago, I really wanted to like the C5; and I fully expected to – it’s

just a smaller C8, after all.

The C5 does have a lot of positives:

it’s very small and light and has excellent optical quality and a very good

focuser. It’s sold as a spotter and indeed gives very good views up to 100x in

the daytime; it makes a great terrestrial telephoto lens too.

Unexpectedly, I didn’t really like the

C5 as a Lunar/planetary scope. Its biggest problem is extreme sensitivity to

seeing due to the 38% central obstruction. On none of the evenings I tested it

could I get a really clean lunar or planetaryimage out of the C5, even though my

refractors were still delivering sharp, detailed views alongside.

The optics weren’t fundamentally faulty or substandard:

the C5 did finally manage clean views in really stable pre-dawn seeing.

The C5 suffers the usual SCT drawbacks

of off-axis coma and field curvature, so for astrophotography you would really

need a flattener. Then there are those arcing reflections. But that said, the C5 does have a real astronomy niche –

for visual deep sky. The combination of lots of aperture for its size, good coatings and enough

well-corrected field of view for all but the most extended objects, makes for

great views of clusters, planetary nebulae and smaller bright galaxies.

Meanwhile, if you do want an

ultra-compact catadioptric for the Moon and planets, I’d go for a Sky-Watcher

Skymax-127: it’s cheaper and gives much better views, though it is a bit bigger

and heavier.

I highly recommend Celestron’s

C5 XLT as a terrestrial spotter or telephoto lens, or for visual use as a

highly-portable deep sky scope. However, it doesn’t deliver the sharpest

planetary views and is sensitive to poor seeing. For the Moon and planets buy a

small APO or Maksutov instead.

Updated by Roger Vine Jan 2018