Choosing Binoculars for Astronomy

Introduction

When I was

a child many popular astronomy books of the time recommended starting off with

binoculars. I tried it, but quickly moved on to a telescope, so it’s only in

recent years that I’ve started to really enjoy using handheld binoculars for

astronomy.

There’s no

doubt that under a dark starry sky, astronomy with a simple pair of handheld

binoculars can be one of the most pleasurable ways of enjoying this hobby: it’s

simple and immediate. Swapping between naked eye and binoculars you can

appreciate the beauty of the whole sky and I know of no better way to learn

your way around the constellations. You can make an evening of it, seeking DSOs

with a red torch and star charts to guide you, or just pop out for fifteen

minutes to catch a few highlights.

So which

binoculars should you choose? In some ways this is quite a difficult question

to answer and much has been written about it in the online forums, some of it

good advice, some of it partisan rubbish from people with a pet make, model or

type. In the following paragraphs I’ll try to take an objective (excuse the

pun) look at buying hand-held binoculars for astronomy.

Binoculars

for Astronomy

Most

hand-held binoculars are designed for birding, not astronomy. Mostly a good

birding binocular makes a good astronomy binocular as well, but in some cases

the requirements do differ. For example, many birding binoculars are

waterproof, but this isn’t exactly necessary for astronomy (although if you

accidentally leave them on the lawn overnight, it might be)! A good birding

binocular needs quick focusing, but this isn’t essential for astronomy either.

Then again, for daytime use you rarely need objectives bigger than 30-40mm: any

more is just wasted because your pupil contracts and effectively masks off (‘vignettes’)

a larger objective. For astronomy, though, your pupil is bigger in the dark, so

you can benefit from the extra light gathered by bigger objectives. So what

characteristics should you look for in binoculars for astronomy?

Objective

size

To start

with, let’s consider the two main binocular characteristics: objective size and

magnification. Binocular sizes are generally quoted as magnification x

objective lens size in millimetres, so that 10x50 means 50mm objectives with a

ten times magnification. Hand-held binoculars come in numerous sizes between

8x20 and 20x60.

Three

of many possible binocular sizes: 15x56, 12x50 and 7x42. These three pairs all

work well for astronomy.

Apart from

looking at the Moon, no binocular with lenses smaller than 30mm are much use

for astronomy and 40-50mm are better. Lenses in the 50-60mm range may make the

binoculars too heavy to hold for long, but may just be worth it in terms of the

brighter images you get and the fainter stars and nebulae you can see.

Light

gathering power is a function of the area of the lens, so 56mm objectives

(about the largest you get in a hand-held binocular) gather twice as much light

as 40mm objectives.

Binocular

Objectives: 42mm, 50mm and 56mm

Power

In terms of

magnification, 7x used to be the recommended power for

astronomy and a good 7x binocular does give a wide, steady view. But in modern

light-polluted skies, 7x and even 8x are too low, tending

to accentuate sky glow from city lights, unless you live under very dark skies.

Such a low power will also make it hard to find smaller deep sky objects like

nebulae and globular clusters, which are easy to find with say a 12x

magnification. Magnifications of 10x and above also give

a much more involving view of the Moon.

About 12x is the comfortable maximum that most people can hold

without shakes blurring the view too much, but you might just get away with 15x

if you have a steady hand or lean on a convenient wall (or bush, car etc!) for extra support. Anything above 15x

would need some kind of mounting.

In short, 10x50 is an ideal

binocular size ideal for a beginner,

but you might eventually find that the effort of using say 12x50s or 15x56s is

worth it for the more involving views you get.

The effect of exit pupil for older

users

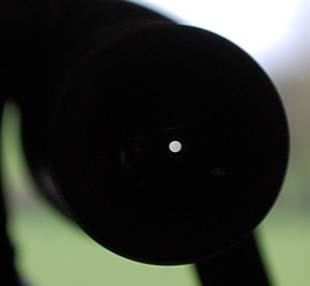

The size of

the exit pupil of a binocular – the little round bright image of the objective

you see in the eyepiece – is simply the objective size divided by the power.

For a 7x50 (the size often recommended in older books) the exit pupil is thus

about 7mm in diameter. But this is a problem. Only younger peoples’ pupil can

open that wide; older people can manage perhaps 5-6mm. So if you’re over forty and buy 7x50s, you are effectively wasting

aperture and 7x40s will seem just as bright!

Binocular

exit pupil

Field of view

Nikon

12x50 SEs - 5 degree true field of view

A wide apparent

field of view is preferable (I like 60 degrees or more, to avoid that “looking

through a straw” feeling), but avoid very wide fields as you often get a lot of

distortion at the edges. Some birding binoculars deliberately leave in some

field curvature for comfortable panning, but this isn’t ideal for astronomy,

where a flat field makes viewing extended objects like star fields more

satisfying. A bright flat narrow field is actually better for astronomy than a

wide, dim curved one. But consider that a high magnification and a small true

field may leave you looking at such a tiny patch of sky that it’s difficult to

find things!

All-in-all a moderate field of view

may work best for astronomy – something like 6 degrees in a 10x binocular. However, some premium designs,

like Swarovski’s EL 12x50s offer a bit more whilst still having a wide,

well-corrected view across the whole field.

Eye Relief

Eye relief

is the distance behind the eyepiece lens at which the image is formed. Short

eye relief means you have to press your eye right up to the eye lens.

This is an

area where a lot of older binos with simple (Kellner type) eyepieces fall short. If you wear glasses then you’ll want good eye relief – 14mm is about minimum for glasses

wearers and 16mm is better.

I recommend

trying before you buy, not least because as far as eye relief is concerned the

size of a millimetre seems to vary widely between manufacturers!

Binoculars

with a lot of eye relief need eye cups to allow for people who wear glasses

(eye cups in) and those who don’t (eye cups out). Click-stop adjustable

eye-cups are much easier to use than the older rubber fold-down type.

Eye

cups extended for use without specs.

Eye

cups folded back for specs wearers

Optical Quality

Good

optical quality is very important. A good easy test of overall optical quality,

as with telescopes, is focus snap – best focus should be easy to obtain, crisp

and definite. If you find yourself fiddling around trying to get best focus,

buy a different pair.

Modern

binoculars should have multi-coatings. These mean that they transmit a lot more

light to your eye and this makes a big difference for astronomy. Reflect a

bright light in the objectives: the reflection should look dim purplish or

greenish and the best coatings make the lenses almost disappear. Whilst you are

at it, look at the interior of the barrels – the best will have ridge baffles

or very matt black paint to cut out unwanted reflections.

These

Nikons have excellent coatings and barrels with ridge baffles

Point the

binocular to one side of a strong light source – a streetlamp or the Moon, NOT

the Sun - to check for internal reflections which are annoying and reduce

contrast: if the view becomes washed out or strong reflections (“ghosts”)

appear, don’t buy. The “Jupiter” test is another good one. Focus on a bright

planet and you should see a well-defined tiny disk with little smearing or

flare of the light; anything else means the binoculars are of poor quality.

Chromatic

aberration (“CA” - colour fringing around bright objects) occurs because the

lenses don’t bring all colours to the same focus. During the day you can check

this by focusing on something with high contrast (tree branches against a

bright sky, for example) and look for purple or green fringes. Most binoculars

show modest CA, and this isn’t so much of a problem for astronomy, unless it is

severe or you like looking at the moon, but very bright false colours are bad

news.

Finally,

avoid zoom binoculars as these are typically poor optically (Leica’s expensive

dual-power Duovids excepted).

Roofs vs Porros

Roof

and porro-prism binoculars

There are

numerous different makes and designs of binocular, but they fall into one of

two main types: porro prism and roof prism (all

binoculars apart from the simplest opera glasses contain prisms to turn the

image the right way up). Roof prism binoculars are the more “modern” type with

straight barrels, porros being the traditional type

with “shoulders”.

Roof prism

binoculars (“roofs” from now on) have the advantage of being generally smaller

and easy to hold, what’s more they have internal

focusing so it’s easier to make them waterproof. Hold on! Before you rush out

to buy a pair of roofs, know this: for a

given level of optical performance, roofs are about twice as expensive as porros (if not three times) and no cheap roof prism

binoculars are much good.

So, for astronomy you don’t need

roofs!

That’s not

to say that a top-quality pair of roofs from the likes of Zeiss, Leica, Nikon,

Swarovski et al won’t be good for astronomy, it’s just that high quality porros may be just as good, but much cheaper. The problem is that very few

high quality porro prism binoculars are made any

more.

Which

Make and Model: Cheap ‘n’ Chearful or High-End

Quality?

The first

thing to understand is that pretty much nobody makes top-quality hand-held binoculars

specifically for astronomers. Smaller binoculars are designed for nature

viewing and birding, larger ones almost exclusively for hunting.

With

binoculars, you mostly do get what you pay for and whilst the more powerful roofs

(10x plus) from any of the top manufacturers (Zeiss, Nikon, Leica, Swarovski)

will be great for casual astronomy, they will all set you back the thick end of

two thousand pounds new. However, with these binos

you will get pretty much everything: light weight, brilliant, sharp images with

a reasonably wide field of view, complete waterproofing and plenty of eye

relief together with twist-and-click eye cups for easy use with glasses. In

fact, if you are used to cheaper binos and don’t find

them very interesting, the fabulous images from these models may really

surprise you!

But what if

you don’t have a thousand pounds plus spare for a pair of binoculars and don’t

need the ruggedness and waterproofing of top roofs? The answer, of course, is a

good pair of porros. In theory and in practice even

the best roofs can’t quite match the clarity and light transmission of the best

porros (Zeiss’ abbe-prism models possibly being an

exception), so you don’t have to be losing out in optical terms. Trouble is

there aren’t that many really good porro prism

binoculars out there, because most birders and hunters go for the waterproof

ruggedness and slim design of roofs.

Probably the

best small porro binoculars are Nikon’s Superior E

line, which are superb optically and mechanically, but are not waterproof.

These can be had in 8x32, 10x42 and 12x50 sizes. Both larger sizes work well

for astronomy. The Superior E line has been discontinued, but as I write (December

2014) you can still get the 12x50s.

Alternatively,

Fujinon’s 10x50 FMT-SX and FMTR-SX (the “R” means

rubber-covered, otherwise they are the same) are excellent optically and

waterproof as well, but much heavier than the Nikons.

Image

Stabilising (IS) Binoculars

Canon’s

12x36 Image Stabiliser Binoculars

The biggest

limitation for hand-held binos is the shakes that

your body will always impart, however steadily you

hold them. Enter, from the mid-nineties, image stabilising (I.S.) binoculars.

These come in various different designs, from passive ones using suspended prisms

and needing no batteries (Zeiss 20x60), to

gyro-stabilised designs (Fujinon) and ones using a

computer to control special prisms which adjust the light path every

millisecond (Canons). By far the most popular are the Canons and I have

personally owned and reviewed the 10x30s and 12x36s (reviews elsewhere on this

site).

I really

liked the Canon 10x30s for astronomy – basically you just push a button on top

and seconds later the image steadies and the resolution dramatically improves;

it’s really as simple as that. Even the 10x30s will resolve more detail than

non-stabilised binos (albeit with less brightness

than good 10x42s) and I used them as just about my only astronomy tool for 18

months when I was living abroad. However, the 18x50s I tried suffered from some

strange effects in use, like changing focus very slightly from moment to

moment, although the level of detail they offered was amazing. Try before you

buy.

Summary

Ten top tips

for selecting hand-held astro’ binos:

1) Power:

10-12 (15-18 with some support or I.S.)

2) Aperture

40-60mm.

3) Weight: Under 1000g is best unless you’re built like The Terminator.

Take 1500g as the absolute maximum.

4) Eye

relief: minimum of about 14mm for glasses wearers; 16mm is better.

5)

Click-stop eye cups are more convenient than the fold down type for glasses

wearers.

6) Always go

for full multi coatings as they yield a much brighter image. Avoid binos made before the mid Eighties,

as they will have single coatings.

7) Make sure any roofs you buy have ‘phase coatings’; porros don’t need them.

8) Roofs

will always be much more expensive than porros for

the same optical quality, so don’t buy cheap ones: buy porros

if your budget is limited.

9) Don’t

buy zooms (Leica Duovids – dual powers, not zooms – excepted).

10) Always

try before you buy if you can, as comfort when holding and eye relief

requirements can vary a lot from person to person.

Best

Buy

Finally, if

you want my specific recommendation for an astronomy binocular, ScopeViews’ best buy is Nikon’s 12x50 SE. These have (very

sadly in our view) been discontinued, but you may still be able to buy them

here: