A Visit to Florence on the Trail of Galileo

It’s said that tourists regularly experience a kind of

nervous breakdown in Florence, overloaded and overcome by Renaissance art and

architecture, masterpieces at every turn. I can believe it – the city can be

almost overwhelming if you like that kind of thing (which I really do).

But for this visit I’m ignoring Leonardo and Michelangelo,

Giotto and Donatello, to concentrate on the cities’ connections with one of the

greatest and most famous astronomers, of Galileo Galilei of course.

History

Galileo’s musician father Vincenzo was from Florence and

moved back there when Galileo was a child (he’s buried there too), but Galileo

Galilei himself was born in Pisa and attended the university there.

Galileo later lived in Padua where he had several children

with his mistress Marina Gamba. Only in 1610 did he

move to Florence, but his connections to the city are long and deep.

Galileo lived in several houses in and around Florence and I

visit two of them, at least in passing. It’s in this great Renaissance city

where he made many of his astronomical observations. Two of his daughters –

Virginia and Livia - were cloistered nearby to become Suor

Maria Celeste and Suor Arcangela. Maria Celeste was

particularly close to the great scientist (see below). Galileo is buried in a

Florentine church.

Galileo’s full achievements are beyond the scope (sorry!) of

this article. Suffice to say he was the first to use a telescope for serious

astronomy and made numerous discoveries, including the four largest moons of

Jupiter, the craters of the Moon, the phases of Venus, sunspots and much else

besides.

Galileo was, of course, eventually tried for heresy in Rome

due to his heliocentrism, but returned to Florence to live out his days under a

kind of house arrest, cared for by his daughter and later his son’s family.

View of Florence from as close as I could get to Galileo’s

house on Costa San Giorgio.

Galileo’s Daughter

I first read ‘Galileo’s Daughter’ by Dava Sobel when it came

out nearly a quarter of a century ago. It’s a biography centred around the

extraordinary relationship between the great scientist and his eldest daughter.

I strongly recommend it as background reading.

It tells a wonderful story and humanised Galileo in a really

poignant way for me. Perhaps that’s just because I had a daughter at exactly

the same age as Galileo did. But at the risk of taking a woke diversion, I

think there’s something really important here too.

Unlike Galileo’s ne’er-do-well son Vincenzo, Virginia Galileo

(aka Suor Maria Celeste - who chose her cloistered

name to reflect her father’s interests) not only had an ‘exquisite’ mind (she

seems to have read and critiqued her father’s works) but was remarkably

industrious and resourceful with it; she also seems to have been a singularly

kind and selfless person.

I can’t help wonder what might have been if the devoted

Virginia had been able to study with Galileo, become his assistant and then

perhaps a scientist in her own right, rather than being shut up in a convent to

die young from the poor living conditions there. As we’ll see, she probably

shares his tomb but doesn’t even warrant a mention on the inscription. She

deserved so much better.

This is an especially interesting question now we’re at last

starting to recognise Renaissance geniuses who happen to have been women, like

the Florentine artist Plautilla Nelli (herself a nun like Maria Celeste) and

the composer Maddelena Casulana.

Getting There

Florence is a huge tourist destination and there are lots of ways

to get there. From the UK, one of the cheapest and easiest is to fly into Pisa

on a budget airline and then take the train direct from Pisa Centrale station –

easily and cheaply booked via the Trainline app which delivers an e-ticket to

your phone. The train ride takes about an hour and is quite scenic, traversing

classic Tuscan countryside.

The only wrinkle is that first you have to get from Pisa

Airport to Pisa Centrale station on the PisaMover, a

kind of horizontal funicular. The problem is that it’s quite hard to find – out

the back of the terminal and then up some stairs.

What to see

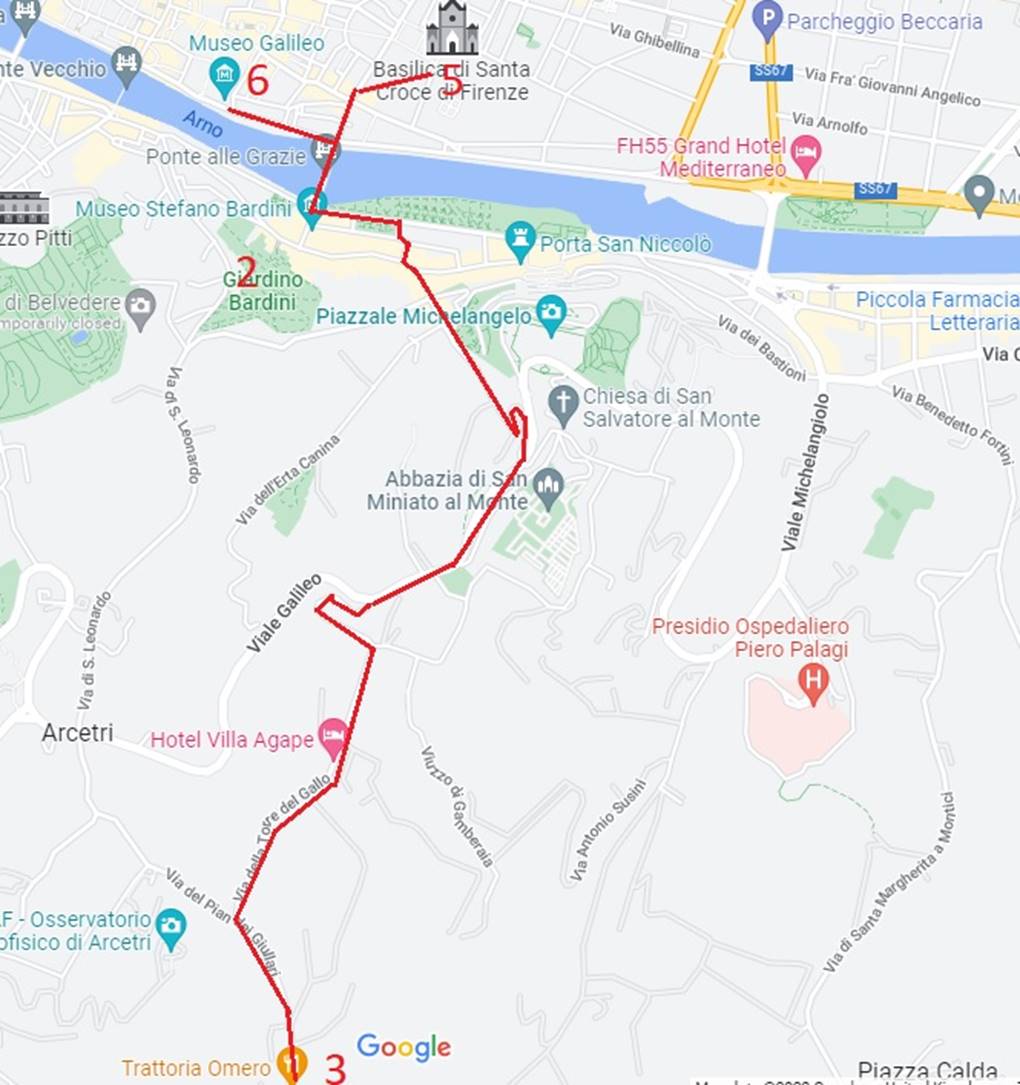

I took in most of the Galileo-linked sights described as a

circular walking tour, so that’s how I’ve ordered it, starting from the statue

outside the Uffizi. The walk itself takes a couple of hours and involves a

steep uphill section at the start and some narrow lanes with little or no

pavement (sidewalk).

I’ve included some annotated Google maps to help you find

your way.

(Note: There are other Galileo-related sites around Florence

and Pisa to seek out, including his house at Bellosguardo.)

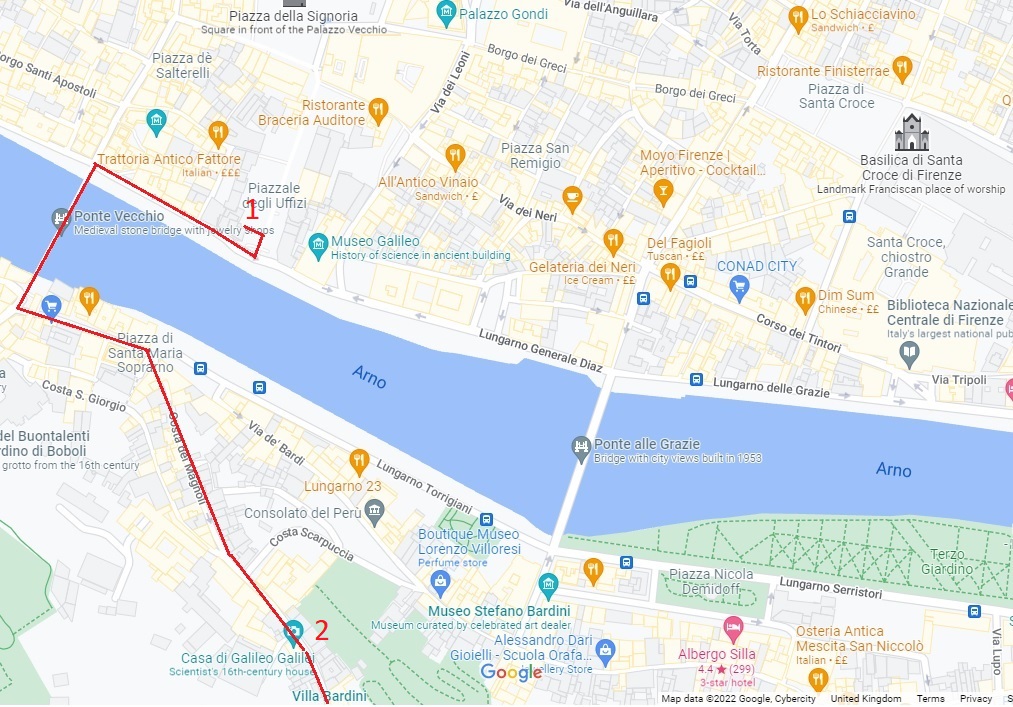

First section of the walk, from the Uffizi to Galileo’s house

on the Costa San Giorgio.

Galileo’s Uffizi Statue, Map Location: 1

Outside Florence’s famous Uffizi gallery is a colonnaded

Piazzale with numerous statues of great Florentines. At the far end, to the

right of the arch that leads out to the embankment above the Arno, is a

full-length statue of our hero, holding a telescope and looking pensively

heavenwards.

From here we take a right along the riverside by some arches

that support the Vasari corridor, then left over the Ponte Vecchio with views

down the river.

At the far end of the bridge, turn left for a short way up

the Via de Bardi and then right through an archway onto the narrow Costa Dei

Magnoli, which merges into the Costa San Giorgio – the street on which you’ll

soon come across one of Galileo’s Florentine houses on the right.

Galileo’s statue next to botanist Pier Antonio Micheli

forever playing air guitar (or so it looks from some angles).

Costa Dei Magnoli looking up towards Galileo’s house on Costa

San Giorgio.

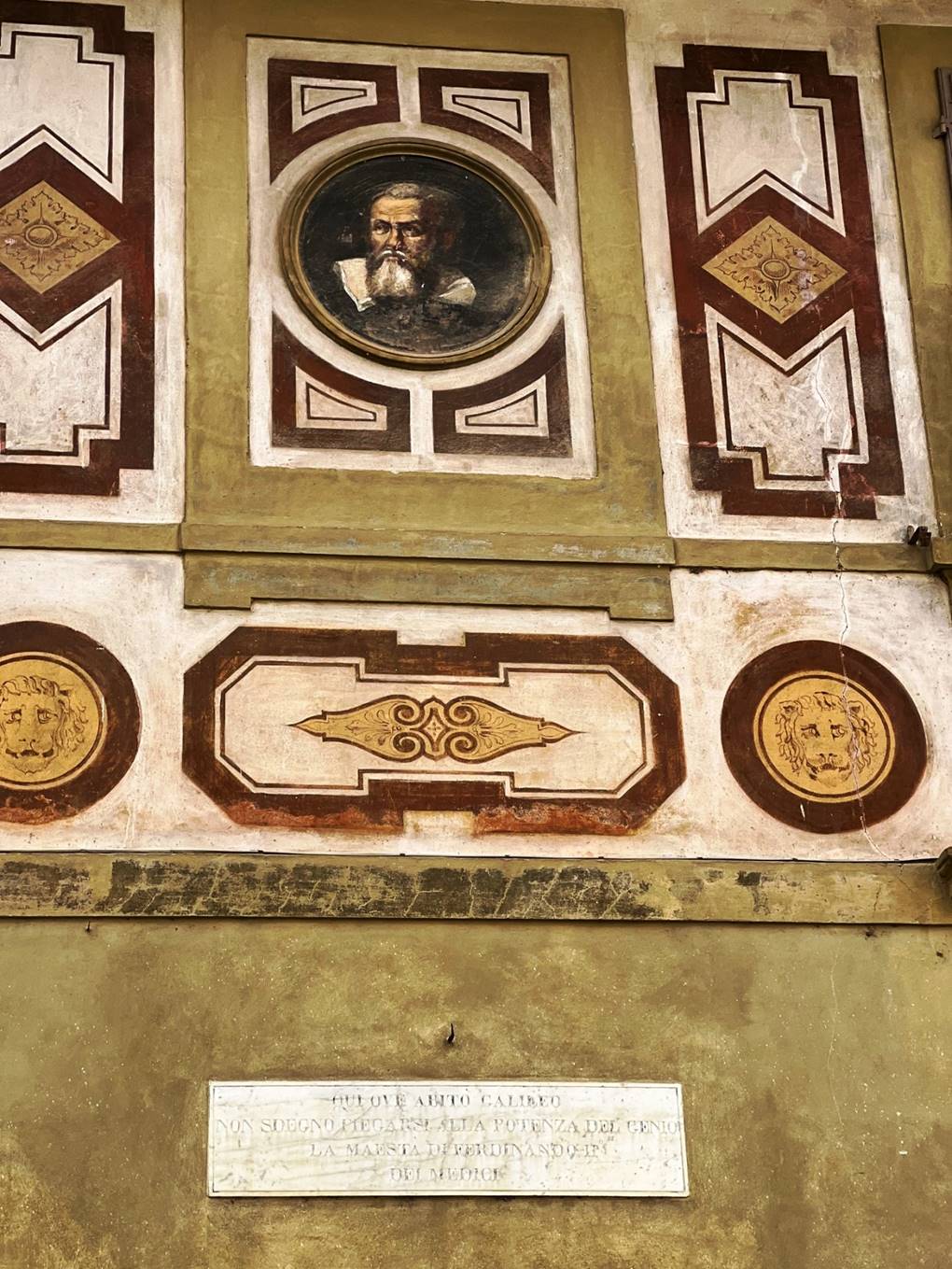

Galileo’s Houses on Costa San Giorgio, Map Location: 2

Galileo helped buy this house as a wedding gift to his son in

1629. His name remained on the deeds and he seems to have lived there for

extended periods during his later years whilst his son’s family cared for him.

Galileo bought the house next door at some point as well.

The attached pair of houses weren’t open to the public at the

time of writing, but there’s a plaque on one and a frescoed portrait on the

other.

From here, continue uphill past Fort Belvedere and merge onto

the Via San Leonardo, then out into the countryside along some narrow lanes

between walls and houses. At the top of this lane, you’ll come across a plaque

marking a house on the right where the composer Tchaikovsky once lived before

coming to a junction with the main road through Arcetri,

the Viale Galileo.

Crossing the main road at the lights, you continue up Via San

Leonardo for a short way, then bear left onto the Via Vincenzo Viviani (named

for Galileo’s last and most famous pupil) opposite a gateway that leads into a

beautiful olive grove that you can see to the right over a wall as you climb

on.

On the way, you pass a gateway in the high wall on the right

which is the back entrance to the Arcetri

Astrophysical Observatory. Bearing right at the top of this lane, opposite the

gate to an impressive villa, you’ll get views over another wall and across

another olive grove to the domes of the observatory and scenic Tuscan hills

beyond.

A little further on is a cluster of houses and then you come

to Galileo’s villa ‘Il Gioiello’ (The Jewel) on the right.

Galileo’s house(s) on Costa San Giogio and dedication detail.

Arcetri Astrophysical Observatory, as seen en route to ‘Il Gioello’.

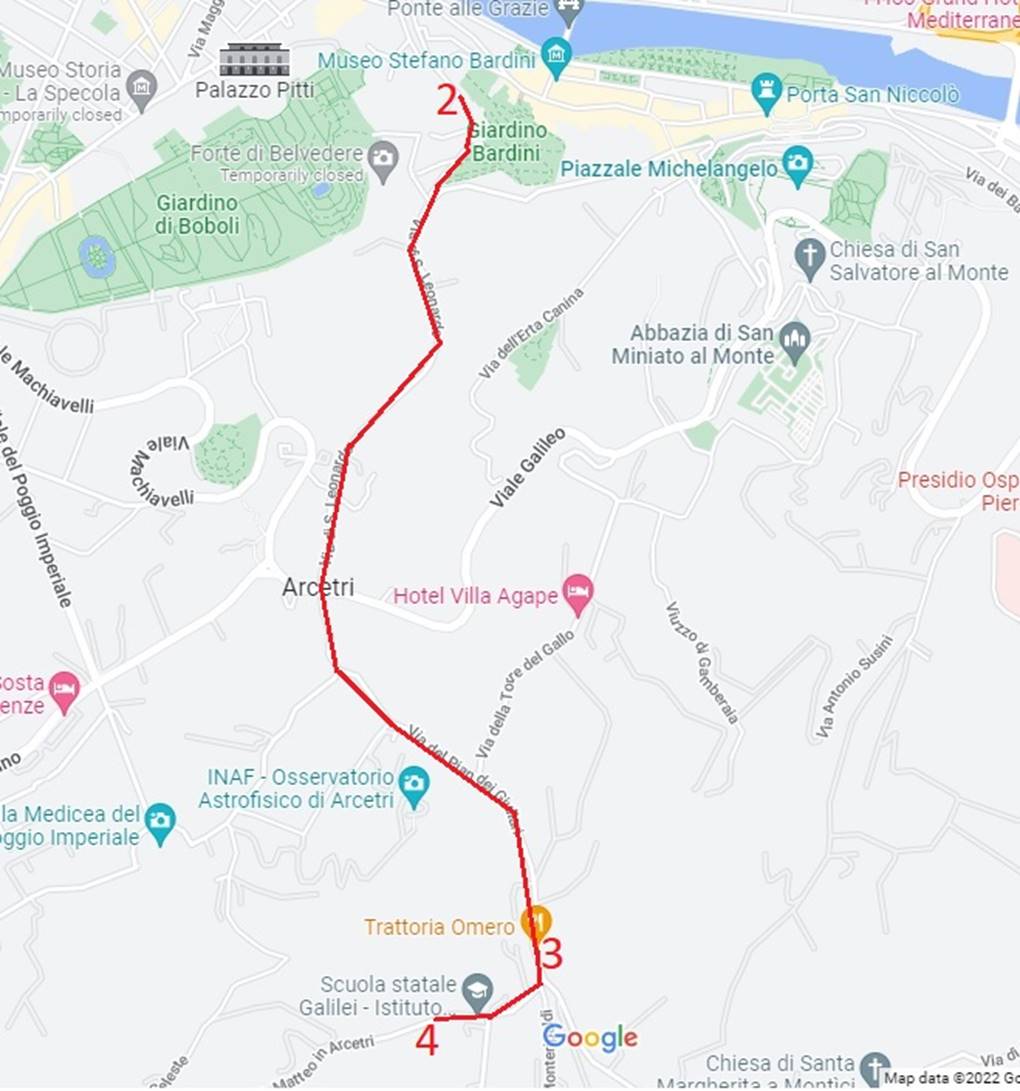

Second section of the walk, from the house on Costa San

Giorgio, past the INAF observatory to the Arcetri

villa ‘Il Gioiello’ and finally the convent site at San Matteo.

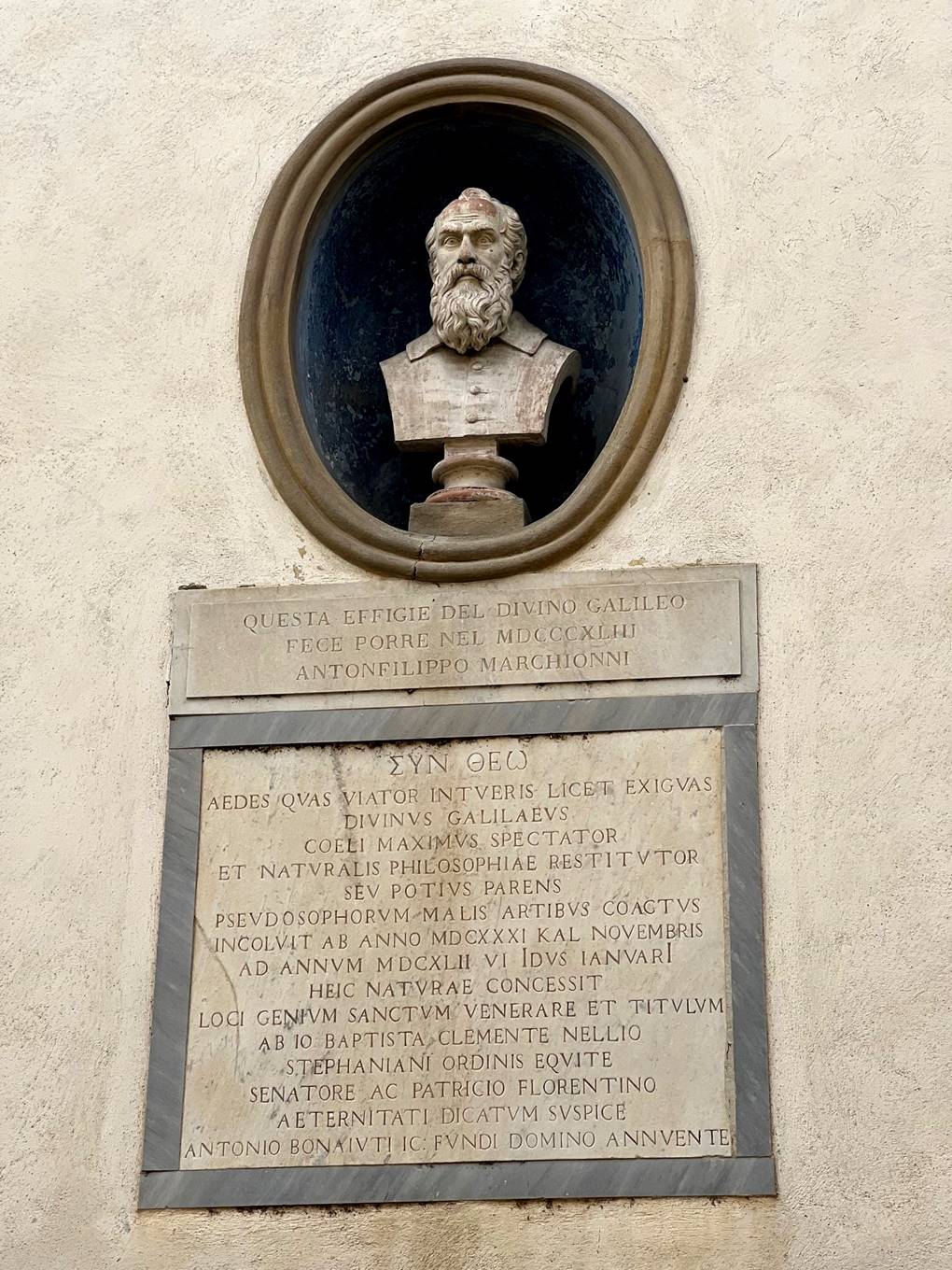

Villa ‘Il Gioiello’ The Jewel, Map Location: 3

Galileo’s daughter Maria Celeste found this villa for him and

he moved there in September 1631. It was just a few minutes’ walk from the

convent where she and her sister Suor Arcangela

lived, so he could visit often and Maria Celeste could tend to her beloved

father’s needs in old age – cooking for him and helping with sewing and making

up medicines for his various ailments, critiquing his writings.

Built in the 14th C. and rebuilt after a siege a

century before Galileo moved there, Il Gioiello featured a sheltered garden and

loggia from where he could make observations. Galileo would receive various

famous scientists at Il Gioiello and he eventually died there in 1642.

The villa is owned by the observatory now and is a national

monument. It bears a 19th C. plaque with a pretty vacuous paean in Greek

and Latin and an equally dodgy bust of a startled-looking Galileo in a niche.

Galileo’s Arcetri villa ‘Il

Gioiello’ – The Jewel.

Dodgy bust and Latin paean (the Greek words mean ‘with God’).

The little church at San Matteo in Arcetri

where the convent used to be.

Site of the Convent at San Matteo where Galileo’s Daughters

were Cloistered, Map Location: 4

You could go back at this point, but having come all this way

I wandered on past The Jewel to the top of the road, turned right down the Via

San Matteo in Arcetri to find the location of Maria

Celeste’s convent.

The convent is long gone, but a small church and cloister

still occupy the same position and there’s a notice about it and Galileo’s

daughters.

From there, head back the way you came as far as the gates to

the imposing villa, but now turn right along the Via della

Torre del Gallo. This has a nice wide pavement (for once!) and leads back down

to the Viale Galileo towards Florence with some magnificent views over the city

and Duomo.

Opposite the marble steps leading up to the Monastery of San

Miniato, cross the road and take a winding left turn onto Via del Monte alle

Croci which leads back to the southern bank of the Arno. From there, the Ponte

alle Grazie takes you back across the river.

Carrying straight on from the bridge down the Via de Benci,

turn right onto Borgo Santa Croce towards the basilica where Galileo is buried.

Third section of the walk, back down from the Arcetri villa ‘Il Gioiello’ to Santa Croce and then the

Galileo Museum.

Some great views as you head back down into town.

Galileo’s Tomb in Santa Croce, Map Location: 5

The basilica of Santa Croce isn’t the most famous in Florence

and lies a few hundred metres from the historic centre in a district that was

once marshy and poor. Still, it’s been described as a kind of Italian version

of the Paris Pantheon because it’s full of great Italians including

Michelangelo, Machiavelli, Rossini and Galileo (and Galileo’s father).

Galileo’s eventual resting place is easy to find: it’s at the

end of the nave directly opposite Michelangelo’s. Galileo’s tomb is in a

similar style with mourning muses and a (perky and youthful) Galileo clutching

his telescope. There’s also an inset showing the ‘Medicean

Stars’ circling Jupiter. But there are some unusual things to point out here.

For one thing, this wasn’t his original tomb. As a

‘vehemently suspected heretic’ Galileo was originally interred with far less

glory in a tiny room under the bell-tower, past the sacristy and at the back of

the Medici Chapel. The room still has a bust of Galileo to mark the spot.

When Galileo was moved to his new tomb, 95 years after his

death, he was treated as a secular saint: a thumb, two fingers and a tooth were

removed as relics and can now be seen in the Galileo Museum near the Uffizi,

our next and final stop. But the weirdness didn’t end there...

When his original brick tomb was broken open, they discovered

two extra coffins. One contained Galileo’s devoted pupil Viviani; the other was

of a young woman, probably none other than his beloved daughter Virginia (Suor Maria Celeste).

It’s thought that Viviani, frustrated at not being able to

give Galileo the grand memorial he wanted to, had secretly arranged for

Virginia to be exhumed from the convent graveyard and moved to Galileo’s tomb;

and in fact, both she and Viviani are in the new one too, though there’s no inscription

for Maria Celeste.

To get to the last stop on our walking tour, head back to the

Arno and then turn right, back towards the Uffizi where you started. Just

before you reach the gallery there’s a small square with the Galileo Museum

just in front of you.

Galileo was originally interred in this tiny room at the back

of the sacristy at Santa Croce.

Galileo’s eventual resting place is at the back of the nave

on the right. Suor Maria Celeste and Viviani are here

too.

The Galileo Museum, Map Location: 6

Like most of Florence’s museums, this one is housed in a

grand old palazzo, situated on the north embankment of the Arno. It’s been

occupied by the museum since the 1930s. When I first went there it was the

‘Museum of the Story of Science’, but changed to the ‘Galileo Museum’ in 2010.

If you’re expecting the Galileo Museum to be mainly about Galileo you’re going to be disappointed. Set out over three

floors, only one large display area in the middle floor is devoted to Galileo.

The rest is an eclectic science-themed mix of globes, armillary spheres

(including one ginormous example), spark generators, astrolabes, compasses and

clocks; and even a room full of wax anatomical dummies!

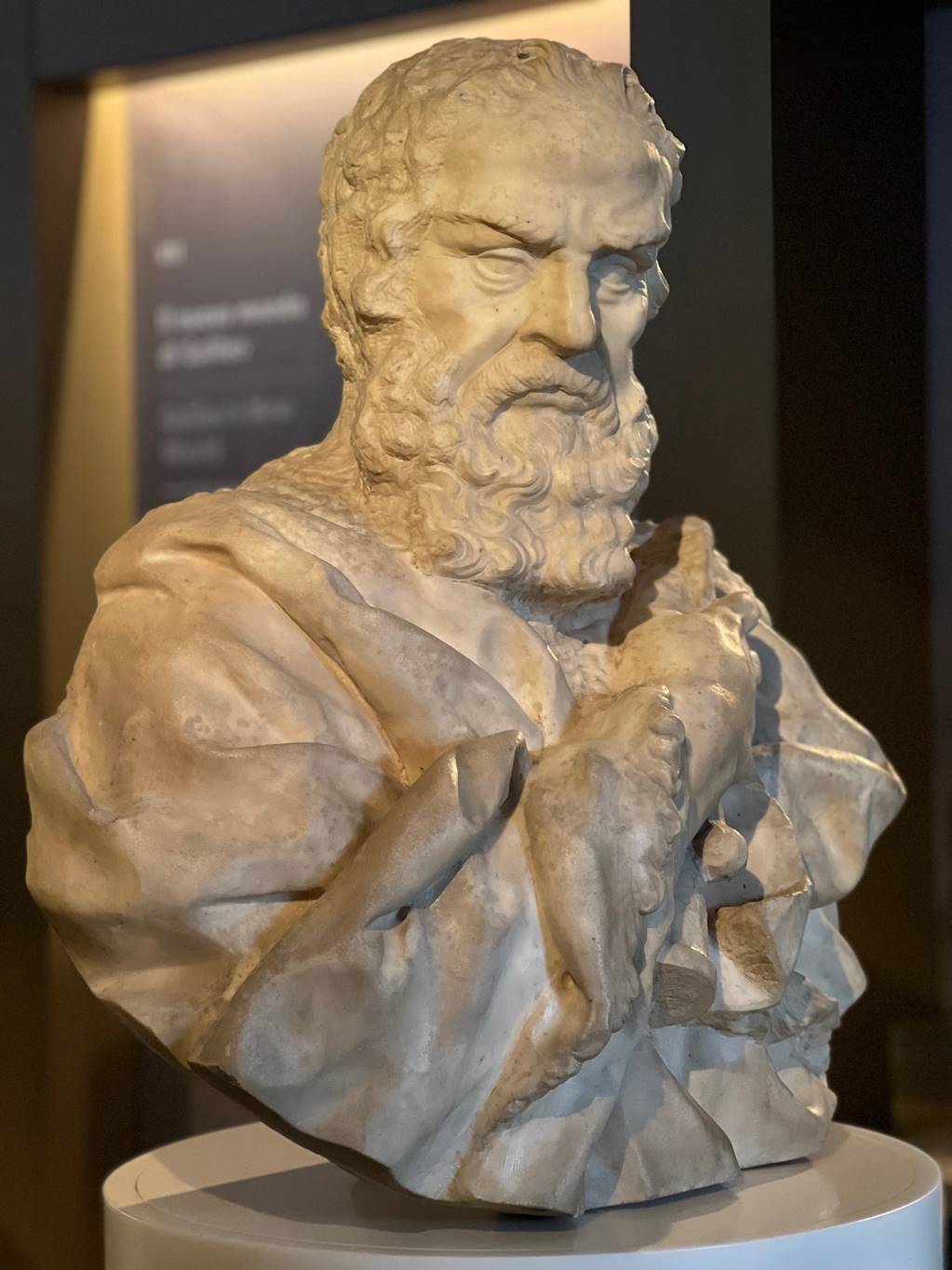

The Galileo space has a bust of the scientist that depicts

him at an older age than any of the others I discovered on this visit. Nearby

is the original lens of the telescope he used to discover Jupiter’s moons, set

in an elaborate frame below two of his original telescopes - iconic and much

photographed objects.

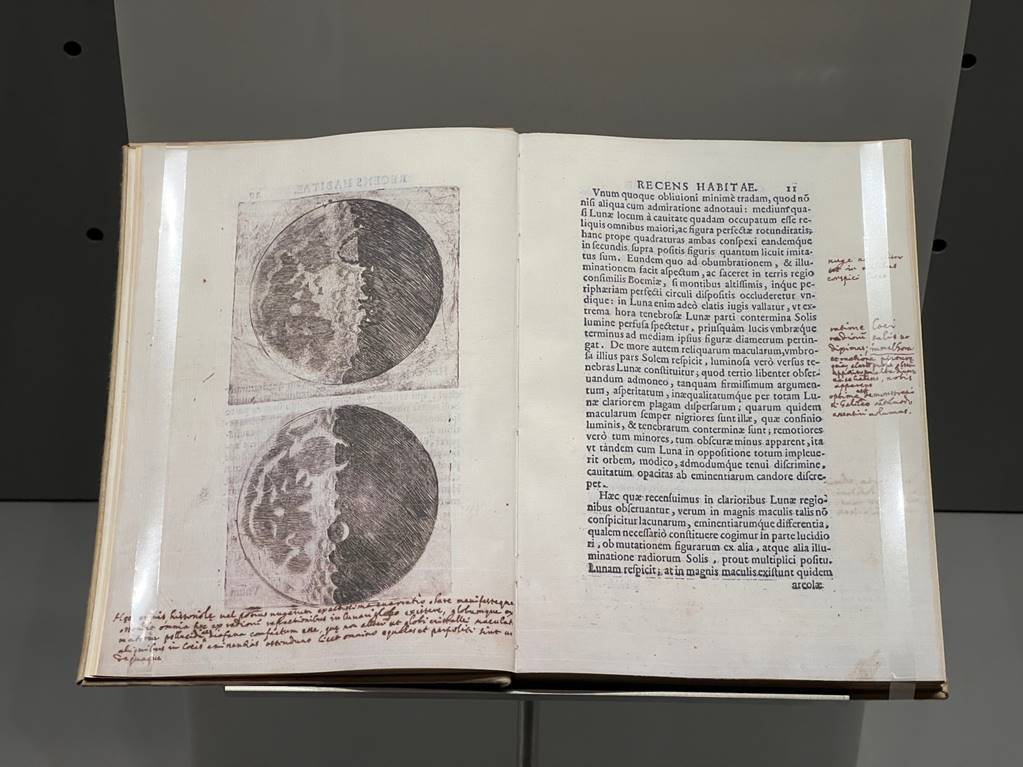

This special Galileo display brings together other artefacts,

like his military compass and original editions of several of his books,

including Siderius Nuncius: open at a page with his evocative drawings of the

Moon.

Also in the Galileo room is a reconstructed telescope broken

down into its component parts so you can see how the tube was built of wooden

slats and how he mounted the objective and eyepiece lenses. There’s an

interesting film loop about his telescope and discoveries too.

Perhaps the most grisly but compelling display is a marble

column containing a pair of reliquaries. One glass container has a single

finger; the other a finger, a thumb and a tooth. These were all removed, you’ll

remember, when his body was moved to its current grand tomb in 1737.

The museum has other astronomy related displays, including a

case full of early 17th C. telescopes, including some that look just

like Galileo’s but much larger! Another display has some early wooden-tubed

reflectors of the sort used by Herschel.

Galileo Museum on the bank of the Arno and next to the Uffizi

gallery.

The Galileo Museum houses many unique artefacts, none more so

than these reliquaries.

The museum holds lots of early telescopes in addition to

Galileo’s.

Me at Pisa.

The Leaning Tower at Pisa

If you flew into Pisa airport, be sure to visit the cathedral

with its leaning bell tower. If you took the train, you’ll probably have to

change here anyway, so just exit the station and go for a walk!

If you’re a fast walker you can easily take in the cathedral

and bell tower in an hour’s round-trip from the station, or stay on in Pisa to

enjoy this beautiful city on the Arno. Yes, but what’s the Galileo connection?

Galileo attended and later lectured at Pisa University; and the city is the

site of a famous Galilean experiment too...

Pisa’s Leaning Tower needs no introduction – it’s one of the

World’s most famous buildings, but is also the place where Galileo is said to

have refuted Aristotle by dropping weights to demonstrate that the heavier ones

accelerated at the same rate as the lighter.

Summary

I love Florence any time, any way,

but devoting a day or two to hunting out the traces of its famous astronomer

was great fun. I’m sure there’s even more to find and I’ll update this article

if I do.

Do just note that I did my walking tour in spring and it’s

best done out of season. At the height of summer, the heat and busy roads might

make it a lot tougher and less pleasant.