A Visit to Lick Observatory

What do you think of when someone says ‘observatory’? Maybe

your own backyard roll-off. More likely, some remote high mountaintop sprinkled

with giant domes and blessed with thin air and steady, inky-black skies, maybe

in Hawaii or Chile. Surprisingly, though, the idea of putting an observatory on

a mountain is quite a recent idea.

Many of the early observatories, even those housing large

instruments, were in major cities. Think Greenwich near London; Pulkovo outside St Petersburg; Meudon

in Paris. Arguably the first observatory to reject urbanity and head for the

hills was Lick Observatory on Mount Hamilton in California.

But Lick isn’t just a first for location, in the late 19th

C. it was also home to the world’s largest optical telescope and that great

instrument is still there. Lick played a role in the Moon landings (right on

topic for my 2019 visit) and still does research. Luckily for you, it’s an easy

place to visit too – close to San Jose and an easy day trip from San Francisco.

History

James Lick, whose slightly unfortunate name the observatory

takes, was born in 1796 on a Dutch farm in Pennsylvania. The legend goes that

he fell in love with a local girl from another farm and asked for her hand in

marriage. The girl’s father’s response was only if Lick had made his fortune

first, which he then set out to do. Lick spent years in south America, made the

demanded fortune trading, and returned to find the girl married to someone

else.

Eventually, Lovelorn Lick moved from South America to

California with a small fortune in both gold and chocolate. The latter sold so

well that Lick persuaded Domingo Ghirardelli to move to San Francisco too.

Lick rapidly increased his wealth by buying up land in San

Francisco at the time of the Gold Rush. Eventually, he became so rich and owned

so much of downtown that when he wanted to build himself a memorial, a giant

Pharaoh’s pyramid in the heart of the city seemed a good idea.

Luckily for San Francisco, Lick had a scientist friend who

dissuaded him. That friend regularly went observing in the hills above San Jose

and suggested to Lick that he might like to build an observatory (then

fashionable for rich amateurs) and make his eternity home there instead. In the

event Lick left a substantial chunk of his fortune to establish the observatory

on Mount Hamilton ($700,000 – the equivalent of $15 million today).

James Lick died on Oct 1st 1876 at eighty years

old, but his observatory wasn’t finished until eleven years later in 1887.

Famously, Lick was exhumed and re-interred in the newly-built brick base for

the Great Refractor and there he remains. His eponymous observatory built itself

a giant refractor and went on to make important discoveries in both

astrophysics and planetary science. Half a century later, the observatory built

another leading instrument.

Lick Observatory has figured in popular space history too: it

was the location for the laser bounced off the Moon as part of the Apollo

program.

In the last few decades Lick has again embarked on important research,

this time in the field of extra-solar planets – initially using a sensitive

spectrograph attached to its 120” reflector. Then in 2013 Lick commissioned a

specially built 2.4 metre telescope, the Automated planet Finder, fitted with a

Doppler spectrograph specifically for detecting exoplanets.

Lick Observatory’s founder is interred in the pier base for

the 36” refractor.

In more recent history, Lick has done seminal research into

exoplanets.

Getting There

Lick is handily close to the Bay Cities, especially San Jose.

Highway 130, a turn off Interstate 101, leads all the way up Mount Hamilton,

passes right through the middle of Lick Observatory and down the other side. A

straight road through the suburbs of San Jose, it leads out into live-oak

foothills and meadows, then becomes the most winding of roads as it gradually

climbs towards the white domes you can see from miles off.

The reason for all those hairpins is that they had to keep

the gradient below 6% for the wagons used to cart everything up the mountain to

Lick (including the Great Refractor and it mount in 1886).

Parking at Lick is fairly limited, but there are a few spaces

on the left of the road beyond the main building. If you book an open evening,

you need to wait until they open the main gates, after which you can drive

right up by the dome for the 36” and park in front (where the views are

incredible).

Lick’s exhaustingly winding access road – built for the

convenience of wagon teams.

Mount Hamilton Road runs right through the site.

What to see

Perhaps the biggest draw of Lick Observatory for most

visitors are its spectacular views. Lick is set atop 4200ft Mount Hamilton and

hosts a 360° panorama. On a clear day you can see the Sierras to the

east, with Half Dome in Yosemite (120 miles away) visible on the very clearest,

its direction thoughtfully marked on the railing behind the dome for the Great

Refractor. To the west, in front of the main building, lie foothills and the

urban sprawl of San Jose. Beyond gleams the Bay, the coast range rising behind.

Many go to Lick simply to stand on the deck and watch the Sun set into that

vast view.

There are other attractions – a gift shop and a shady

courtyard café behind the main building, but mostly it’s about those views.

For those interested in telescopes, Lick has at least three

historic examples and you can visit two of them: the famous 36” Great Refractor

(the world’s second largest) and the 120” Shane reflector.

There are various smaller domes containing a variety of other

instruments around the site and some interesting displays on the lobby walls

too.

Most visitors come for the sunset.

The main observatory building has a grand air, interesting

displays like this early Pacific Standard Time chronograph.

Lick’s first major instrument, the Crossley Reflector, lies

in a dome at the south end of the site.

The

36” Crossley Reflector

The

first telescope installed at Lick was a 36” reflector, gifted by an

English politician named Edward Crossley from Yorkshire. The telescope had been

built in 1879 by one Andrew

Ainslie Common who used it to make pioneering long-exposure deep sky

images of the Orion Nebula from his backyard roll-off shed observatory in

Ealing (a London suburb, where I was born incidentally). The 36” reflector is

regarded as perhaps the earliest astrograph.

In 1886, Crossley bought the 36” when Common got aperture

fever and built a 60”. Crossley moved it to Halifax and seems to have used it

little before advertising it for sale in 1895. The director of Lick contacted

Crossley, who eventually agreed to donate the telescope. Funds were raised for

shipping and the Crossley Reflector, along with its dome, crossed the Atlantic

to become the largest instrument in America for some years.

However,

the Crossley Reflector hasn’t been used since 2010 and isn’t open to the

public. You can see the British-built Crossley dome, lying below the main site

on a small peak to the south of the main complex.

Dome

for the 36” refractor, day and night.

Visitors

line up for a look through the eyepiece of the 36” Great Refractor.

The 36” Alvan Clark Refractor

The largest dome on the south side of the road houses Lick’s

most famous instrument – the 36” aperture Great Refractor.

The history of the Lick 36” refractor began in 1880, when the

glass blanks for its doublet lens arrived from Paris by ship and work started

to grind them at the famous Alvan Clark works in

Massachusetts.

The finished lenses were transported to the west coast by

train, then up the mountain by horse and cart, to arrive onsite in 1886. The long

delay was because one of the lenses broke on the journey and it took many

attempts to grind another

The 36” saw first light in 1888 and was for some years the

largest telescope in the world. It made some important discoveries too,

including Jupiter’s moon Amalthea by E. E. Barnard soon after it was

commissioned.

The 36” objective is the second largest Alvan

Clark ever made and the largest still in operation (the largest, the 40” at

Yerkes, is no longer open for visits or views). The ‘Great Refractor’, as it’s

also called, is a huge and magnificent thing, with a 57-foot long tube and a

gigantic equatorial mount.

To add to the slightly Steampunk, Gothic-novel ambience of

the place with its parquet floor, riveted plates, capstan wheels and spiral stairs,

is the presence of James Lick himself, seeing out eternity in the base of the

pier. You can visit the simple plaque on his grave by climbing down narrow

wooden steps by the side of the dome and walking under the giant girders that

hold up the (once moveable) floor.

The Great Refractor is now mostly used visually for outreach

and is open to tour groups in the summer, but gets heavily booked up. Viewing

through it is a great experience and highly recommended. The moving floor isn’t

working, so be aware you have to climb a big ladder to the eyepiece. Meanwhile,

the telescope operator has to climb the pier with a harness and hard hat to

operate the mount!

The 36” still gives incredible views, but does need some

restoration work to avoid going the same way as the 40” at Yerkes

You can visit the 36” on a tour, or better yet book onto one

of the ‘Summer Series’ events which often combine a concert with an evening’s

viewing (get in quick, because tickets sell out quickly in April every year). I

have written a review of the 36” and the experience of viewing through it here.

Front and back of the 120” Shane Reflector dome. Building for

the Hamilton spectrograph at the Shane’s coudé focus

is on the right.

Walkway around the Shane dome gives a panoramic view. I met a

famous astronomer here (not pictured!)

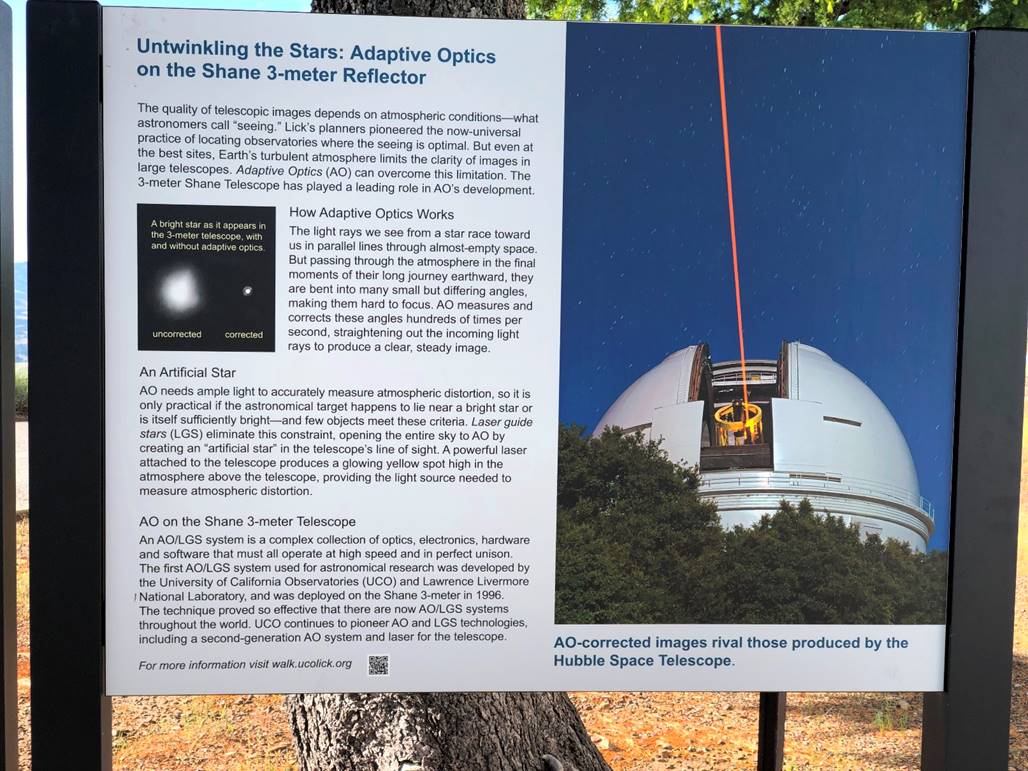

Views of the 120” Shane reflector, showing its adaptive

optics laser and prime focus.

Instruments at the Cassegrain focus.

Tank for re-coating the main mirror lies in the basement of

the dome.

Placard about the adaptive optics laser and the little hut

used by observers to shut it off if a plane or satellite strays into its beam.

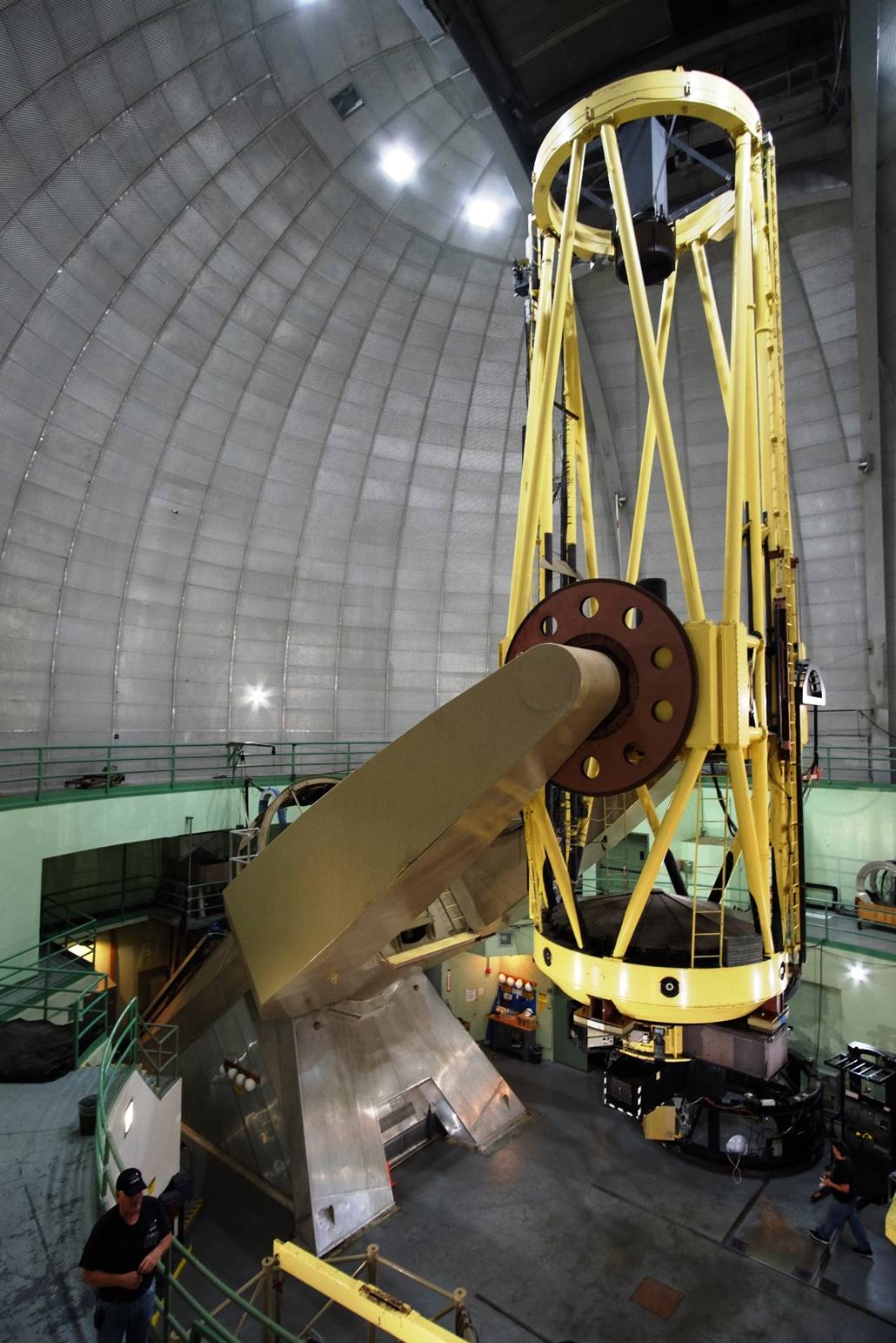

The 120” (3m) Shane Reflector

Across the other side of the mountain top, on the north side

of Highway 130 is another cluster of buildings, including an even larger white

dome which houses an even larger telescope, a reflector this time, the Shane

120”. That dome, all 275 tons of it, has a double skin to help insulate the

telescope from the day’s heat.

Like the 36”, and despite being less

well known, the Shane 120” was among the largest optical telescopes in the

world after first light in 1959. It also has the distinction of using one of

the first mirrors made of the then-new material Pyrex (great for oven-ware for

precisely the reason it’s good for mirrors – it is virtually free from

expansion when it heats up).

The Shane’s 120” mirror – 15 inches

thick and weighing four tons - was cast and ground as a trial run for the (much

more famous) 200” at Mount Palomar. The whole ‘scope and mount weigh 145 tons.

Like many modern big research

telescopes, the Shane has three focus points for the placement of instruments: prime,

cassegrain and coudé. The

latter directs light out to a separate building containing the high-precision Hamilton

spectrograph, which pioneered research into exoplanets.

The earlier big reflectors at Mount

Wilson look like an Edwardian bridge, with a mass of small girders. In

contrast, the Shane has an Art Deco simplicity about the design, same as the

more famous Palomar 200”: a simple truss-tube to support the mirrors, held by

an elegant fork mount in a retro-brown to match the yellow truss-tubes.

The Shane is just a human lifespan

newer than the Great Refractor, but looks (and in many ways is) a thoroughly

modern instrument by comparison: it still does research and benefits from a pioneering

laser adaptive optics system – a first when deployed in 1996 (since replaced

with a 2nd generation system).

Just outside the dome, on the edge of

the summit plateau and with a great view, is a strange little hut like an old

telephone booth but with a glass roof. This hut is for an observer to shut-off

the laser (with a ‘big red button’, they said) when an aircraft or satellite

threatens to stray into its beam: a boring job but a well-paid one, they

jokingly told us. This is necessary because the laser is quite a powerful one

(10W), thousands of times more powerful than a typical laser pointer!

Descending into the dark basement of

the Shane dome, visitors are shown a huge red tank where they re-aluminise its

mirrors.

Going in the other direction, it’s

possible to walk out onto a gantry around the dome for spectacular views across

the site, to the 36” dome and the hills beyond. The other domes are opening for

the night as you watch. The gantry is quite narrow though, so not ideal if you

suffer from vertigo.

After my visit, I stayed on a for a

while to capture some long-exposures of the observatory and the stars. Nobody

seemed to mind. A perfect end to my evening at Lick before facing the long and

tedious drive back down all those bends, dodging jaywalking raccoons.

Lick observatory is well worth the

tortuous drive up from Fremont, especially if you’ve booked an evening

observing on the 36” Great Refractor.