Snapping the

Moon with a Super Zoom Camera

Olympus

SZ-15 with 24x optical zoom

When I got

into astronomy in my early teens one of the first things I wanted to do was

photograph the Moon. Unfortunately it wasnít so easy in the pre-digital era and

I ended up equipping my own darkroom so I could push the slow ISO black and

white films of the time.

These days

you donít need a darkroom, but you do still need a telescope and ideally an

interchangeable lens camera and a T-adapter. Or do you?

If you canít

(or initially donít want to) spend the £Several Hundred plus youíd need for a

scope, camera and adapter, there is another way. You (or someone you know) may

have a compact camera with a super zoom lens Ė loads of families have them

kicking around unused between holidays. If the zoom is ten times or more, you

can get interesting snaps of the Moon that show more than the naked eye. If

your zoom is over twenty times, you can get Moon snaps that are quite

surprisingly detailed. Hereís how.

The Olympus

SZ-15

The Olympus

Iím using for this article is an SZ-15 SuperZoom

point and shoot camera, but I donít want

to give the impression Iím specifically recommending this particular model; Iím

not. In fact, one of the much larger and more expensive super zoom bridge

cameras would doubtless be better (though less likely to be just lying idle

around your home since the last family holiday).

There are a

series of similar Olympus models, from the SZ-10 on, that include a long zoom

lens; the obsolete models can be had pretty cheaply. Other manufacturers make

super zoom compacts as well and some of them may be

better than this Olympus. I chose this Olympus because it is cheap, available

and common. Iíll quickly review its main characteristics, but I donít want to

go into full details here Ė there are numerous reports and reviews online.

Design and

Build

In many ways

the Olympus SZ-15 a typical pocket-size point-and-shoot consumer camera: small,

light and simple. Itís larger than a lot of pocket cameras; but itís still relatively

tiny.

Build

quality appears reasonable, but nothing special. It has just enough brushed

aluminium to prevent it from seeming really plasticky.

Aimed at casual users, it provides a simple set of program modes and it doesnít

even have fully manual override; it just happens to have an unusually long

zoom.

Lens

So what

about that lens, then? The specs say that it goes from 4.5mm to 108mm focal

length. But combined with a very small sensor that gives a claimed Ďequivalentí

image scale to a 25mm Ė 600mm! When they say equivalent, though, itís not clear

to what exactly. An APS-C DSLR? A

full-frame DSLR? From my experiments, it would seem they are comparing

it to a 35mm camera (i.e. a full-frame DSLR), because the image

scale at full zoom is smaller than a 600mm lens with my APS-C cameras.

Nevertheless, a maximum zoom

equivalent to a 350-400 mm telephoto lens on an APS-C camera is still impressive.

For use on the Moon we should end up with an image scale similar to that from a

small refractor telescope.

Sensor

The SZ-15 has

a 1 / 2.3Ē sensor Ė the smallest size generally available (which is why itís

able to offer such a powerful zoom).

The sensor

has 16 Mp which is a lot to cram into such a tiny

area. The result of this is relatively poor low-light performance. The SZ-15 offers

ISOs settings from 100 to 1600, but it generates a lot of noise above ISO 400,

despite doing some kind of automatic dark-frame subtraction.† That doesnít concern us here because the Moon

is bright and we wonít need high ISOs. Suffice to say that if you were looking

for a point-and-shoot camera to do landscape astrophotography it wouldnít be

this one. Interestingly, the Sony with a 10x zoom (see Moon photo at end) does

much better for landscape astrophotography than the Olympus, but itís not as

good for the Moon.

Image Stabilisation

The SZ-15

includes a stabiliser: itís noisy, but seems effective. You can disable it if

you are using a tripod.

Setup for

Imaging the Moon

Having taken

a brief look at the camera, letís consider how to set it up to try to get some

images of the Moon.

Mounting on a tripod

To start

with, you really need a tripod. Thatís not because you will be using long

exposures Ė the Moon is bright so you wonít be. From the point-of-view of

shakes you might be able to get away with hand-held photos using the stabiliser.

But there is a problem: the SZ-15 has no manual mode, so to force it to focus

and expose correctly you need to centre the Moon precisely in the field of view

and that means using a tripod. Like most cameras, the SZ-15 has a ľ-20 thread

on the base and you can use just about any cheap, light-weight photo tripod.

So, you zoom

into the maximum optical zoom of 24x (there are

digital zoom setting to twice that) and snap away at the Moon. What youíll get

will be something like this:

Clearly this

is no good: the camera isnít exposing the view correctly, itís trying to get an

average for all that dark sky and ending up massively overexposing the Moon.

You could try exposure compensation, but even setting the maximum value of -2

doesnít improve things much.

Enabling Spot Focus and Metering

If this

camera had manual settings, weíd focus and expose manually, but it doesnít. Instead,

you have to force the automatic focus and exposure to adjust for the Moon, not

the surrounding sky:

1. Turn the camera on and hit the menu

button the back.

2. Scroll down to ĎAF Modeí and select

ĎSpotí

3. Now scroll down to ĎESPí and select

the icon with a dot in a square instead.

4. Whilst you are at it, find the

ĎCompressioní setting in the same scroll-down menu and make sure itís set to ĎFineí.

This produces the best quality JPEGs (this camera doesnít produce raw files).

You have now set the camera up to

adjust focus and exposure only for the spot in the centre of the field.

Setting Exposure Mode and ISO

You will

need to select the correct shooting mode and check a couple of other settings.

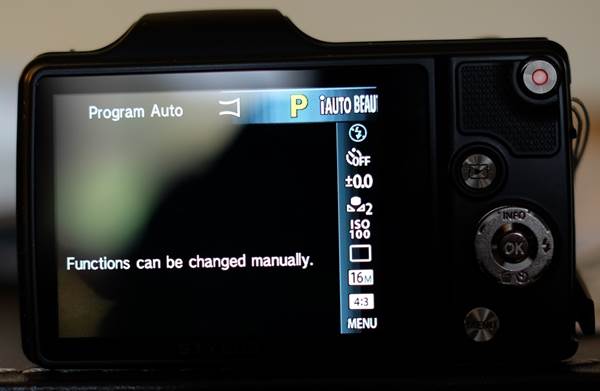

Turn the

camera on and hit the ĎOKí button in the centre of the control wheel on the

back.

1. Scroll left and right to select ĎProgam Autoí and hit OK.

2. Now scroll down and select ĎISO 100í.

This sets the camera to minimum light sensitivity (like we said, the Moon is

bright), but maximum picture quality.

3. Scroll down again and select Ď16Mí

for maximum picture size.

4. Scroll down yet again and select

Ď4:3í for the picture format.

The camera is now setup as well as it

can be for our Moon shots.

Choosing

your Moon Phase

Non-astronomers

are often surprised to hear that Full Moon is the night a lot of astronomers

shrug their shoulders and stay-in watching the telly: Moonlight blots out

anything other than planets, whilst the Moon itself looks least interesting

when full. Itís the same reason photographers donít much like midday on earth Ė

no shadows and a bright sun flatten the landscape and wash out colour and

detail. The effect is the same for us, so that full-Moon is the least ideal

phase to snap. You will get more interesting photos when shadows are

highlighting the topography. Even so, if itís full Moon, still get out there

and have a go!

In the long

run it might be fun to try capturing as many different lunar phases as you can.

Crescents are arguably the most beautiful, but the thinnest crescents very

early (and late) in the Moonís monthly cycle are difficult to find because they

are close to the Sun and can be a real challenge to capture with your camera!

Snapping the

Moon with your Super-Zoom

After all

that setting up, you might think that getting out there and actually snapping

the moon is a formality. Not quite.

The first

thing to do (once youíre setup under the Moon) is to get it precisely centred

in the metering square in the centre of the frame. This is necessary or the

metering wonít expose for the Moon, but for the dark sky around it, as we saw

at the start.

Once youíve

done that, press the shutter half-way. The camera should now try to focus and

adjust exposure for the Moon. It may take a little while to settle down,

especially in terms of focus, but it will get there in the end! When it has

done it gives a beep and you can snap away.

Make sure

you regularly download and review your efforts. You may find that playing

around with the ISO setting and the exposure compensation can improve your

shots.

If your

images are blurry it might be camera shake. Try incrementally increasing ISO

from 100 to 200 and up to 400 to force the camera to use higher shutter speeds,

until any camera shake has gone. Precisely which setting

works best will depend on the brightness of the Moon (i.e. its phase) and the

stability of your tripod.

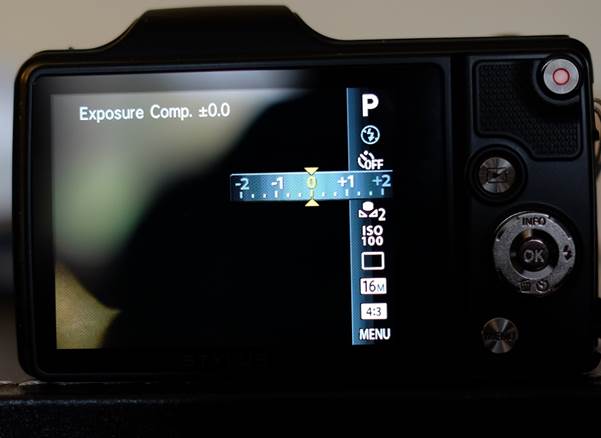

If your

photos look washed out, try setting the exposure compensation to under-expose

slightly. Do this by scrolling down through the menus in shooting mode to the

fourth item down: ĎExposure Comp.í. Try setting this to values between 0 and -1

(beyond -1 is too much, whilst +ve values will

over-expose).

Post

Processing

Once youíve

got some photos you are happy with, you can improve them further using

processing software. There are numerous free packages to do this and you only

need the basics.

The one

thing to understand about processing is go slowly, apply subtle changes

incrementally.

Sharpness

Sharpening

your photo slightly (but not too much) will likely improve it. Adjust up the

sharpness in tiny steps just until it looks well defined. Too much sharpening

looks very artificial.

Contrast

Again, a bit

of extra contrast will improve most Lunar photos, but too much ends up with a

very artificial look. However, really pushing sharpness and contrast produces a

rather Ďpaintedí impression which can be pleasing.

Colour temperature

You may find

that colour of your Moon shots is wrong. Typically they may be a bit yellow

because the camera has chosen the wrong white-balance. Again you can fix this

in post-processing, either directly with white balance (if the package allows

it), or with colour temperature. Experiment until you get the proverbial fifty

shades (well maybe with a bit of buff thrown in)!

Results

Moon taken with

Olympus SZ-15 at full digital zoom

This was the

best image I was able to get, after several sessions. Itís not great Ė itís

still a bit blurred, perhaps from lack of perfect focus, or because optical

quality is mediocre. It also has a mild colour cast. Itís just a cheap camera

after all! Still, itís an interesting photo with the sort of detail you get through

binos and you can make out many of the main features,

including a few prominent craters like Langrenus at

top right and bright Proclus with its rays at the edge of Mare Criseum; you could easily get an atlas and identify more.

For

comparison, below are (cropped) Moon photos taken with three other zoom cameras

and lenses. As you can see, the best was taken with a Fuji XM-1 and its

50-230mm kit lens. The Fuji is also a compact camera, but one which takes

interchangeable lenses and allows full manual control; itís a fair bit more

expensive and specialist than the Olympus. Compared with the cheap DSLR zoom

lens and the Sony with a smaller (10x) zoom, the Olympus does well.

From these photos, it seems optical

quality and sensor performance are probably more important than shear zoominess, so if you have a zoom camera lying around Ė

especially a bridge camera - you may well be able to do better. Have a go!

Moon taken

with Fuji XM-1 Camera with 5-230mm kit lens

Moon taken with Nikon D5100 with 50-200mm lens.

Moon taken

with Sony NX camera with 10x zoom