Nikon 18x70 IF WP ‘Astroluxe’ Review

When I got my first high-power big

eye binoculars, more than a decade ago now, they were a revelation for

hand-held astronomy. By day their view was horrible: dim, narrow and jiggly.

But for astronomy they were amazing because they just showed me so much more.

Since then, every step-up in magnification and aperture has been more of the

same – heavier, harder to hold steady, yes, but delivering so much more

deep sky.

This progression towards higher

powers and bigger objectives has to end somewhere. And it ends here. Because

these Nikon 18x70s are, probably, the largest and most powerful bino’s I could

feasibly hand-hold. I’d had my eye on a pair for ages and even sold off my

much-loved Swarovski 15x56 SLC HDs to make way for them.

So let’s find out whether there’s

anything to be gained by supersizing my astronomy bino’ habit to something as

large and heavy as the 18x70s, or whether I’ll be backing off to a(nother) pair of 15x56s after all.

But this isn’t just an astronomy

review, because for the domestic market Nikon don’t label these as an astronomy

binocular at all. In reality, they probably designed them for daytime marine or

coastal use, perhaps more like this:

At A Glance

|

Magnification |

18x |

|

Objective Size |

70mm |

|

Eye Relief |

15.4 claimed, measured (but see text) |

|

Actual Field of View |

70m/1000m, 4° |

|

Apparent field of view |

64.3° |

|

Close focus |

81m (!) claimed. |

|

Transmissivity |

~95% est. |

|

Length |

~260mm w/o eye cups |

|

Weight |

1954g measured. |

Data from Me/Nikon.

What’s in the Box?

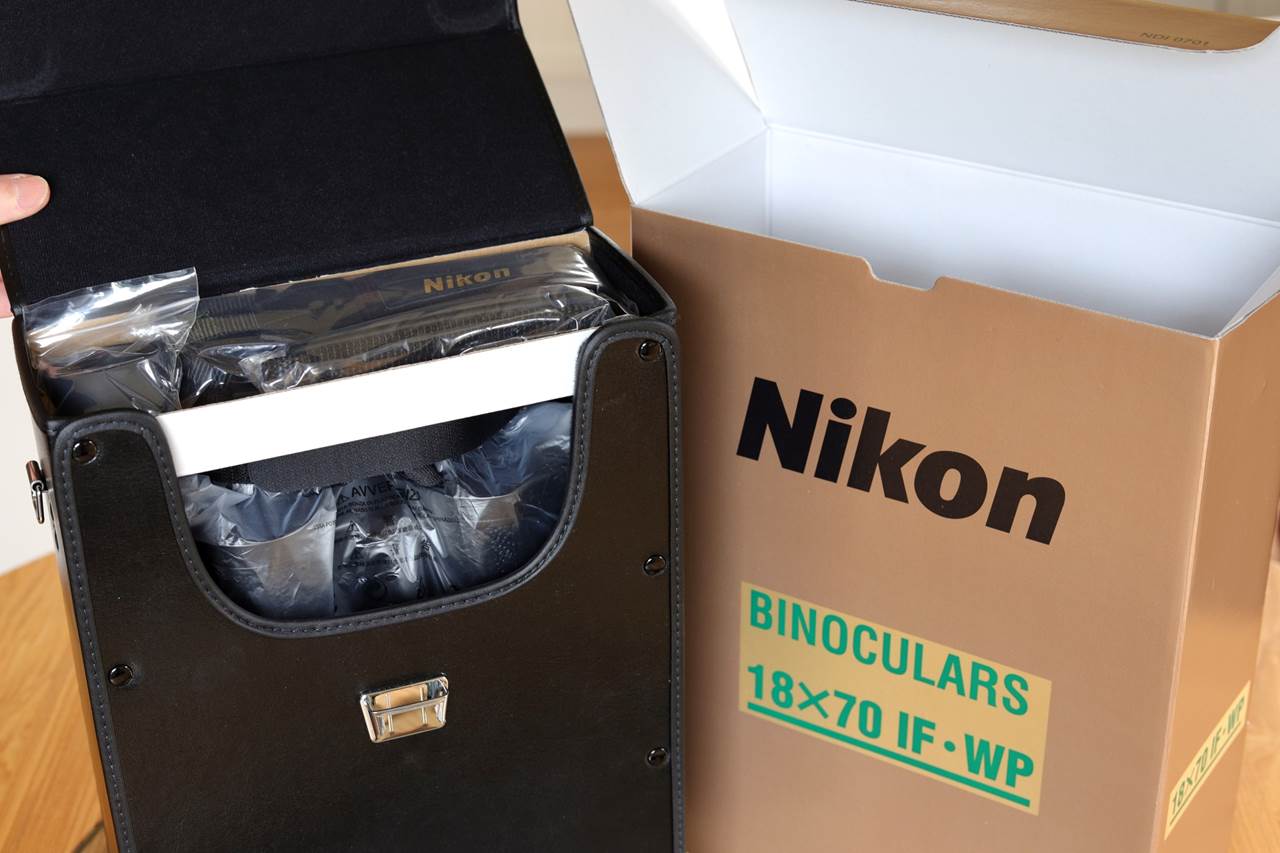

I really enjoyed unboxing these.

That huge and thick gold carton; the 1970s stick-on labels (‘cos they’re so

low-volume they don’t get a unique box); the smell of new optics and leather.

Design and Build

These

18x70s are part of a range of traditional rugged and waterproof (WP) porro-prism binoculars which share a design common decades

ago, with massive prism housings, independent focusing (IF) and a big,

leather-covered body. You can find similar looking binoculars from the ‘70s and

‘80s made by Canon, Fujinon, Takahashi, Pentax and

others, most of which are now defunct.

Nikon

still (as of early 2021) make five models in this style, comprising two 7x50s,

two 10x70s and this single 18x70 variant. All are still 100% manufactured in

Japan, including the case and other accessories.

It’s

important to note that these apparently similar binoculars actually have

significant differences. For example, these 18x70s are the only ones fitted

with wide field oculars, the others have quite narrow fields of view.

Only two

models – the 7x50 Prostars and one of the

10x70 variants – feature ‘SP’ glass and so are specifically designed for

astronomy. No one seems sure what ‘SP’ glass is; I suspect non-ED glass but

with high homogeneity, low inclusions, bubbles and striae for the best stellar

images. Those ‘SP’ 7x50s and 10x70s are much more expensive than their more

basic (but almost identical) cheaper versions and also have field flatteners.

Curiously,

even though the 18x70s are badged ‘Astroluxe’ in some

markets, their acronym list doesn’t include ‘SP’. And as I said at the start,

in the Japanese market there’s little evidence they were intended for astronomy

at all.

Note: in

these images, the standard hard eye cups have been replaced with Tele Vue items

– see below for an explanation.

Body

These are most people’s idea of binoculars, but bigger:

black, made of metal, with long barrels and smelling of leather. They look

enormous compared to a regular big-eye hunting binocular, never mind birding

bino’s.

Huge they are, but the 18x70s aren’t as heavy as you expect.

At just over 2 kg, they’re only about 500g heavier than a pair of Fujinon 7x50s or 10x50s.

Build quality is superb, with glossy leather and lustrous

black paint, those red-rings around the objectives and the screw-on prism

covers like some piece of military hardware.

The surprising thing about these is that they are in fact

waterproof, though they don’t look it, designed for marine use. With no rubber

armour they’re obviously not going to be as rugged as say a pair of Fujinon 16x70 FMTR-SXs, though.

Focuser

These have individual eyepiece focusing – you twist each

ocular to focus it separately. At first these were unusably stiff, but after

some forceful twisting they freed up nicely to become oily smooth and well

weighted. Unlike the 7x50 Prostar version, though, here depth of field is very

shallow due to the high power. That means lots of inconvenient focusing between

targets; but for astronomy it’s a non-issue of course – set and forget.

Optics - Prisms

These are obviously (?!) a traditional Porro-prism

design, with the caveat that the large prism housings likely mean oversized

prisms for good off-axis brightness. Unlike roofs, porro-prisms

need no special mirrors or phase coatings.

Optics - Objectives

The objectives are just big achromatic doublets, with the

crown glass in front. Optical quality is clearly very high, as are the coatings

which are very transparent.

Internally, the main barrels are just flat black painted, but

the connection to the prism housings serves as a baffle and the housings

themselves have been meticulously lined with flocking material. I was surprised

to see some dust adhering to the walls of the barrels inside, but it may come

from that flocking material.

Look past the premium coatings to find heavy-duty prism

straps and careful flocking.

Optics - Eyepieces

The eyepieces are a complex design that give a very wide (for

bino’s) apparent field of 64° apparent

and 4° true. They have quite large eye lenses, but the oculars themselves are

quite small. I’m guessing they are some kind of Erfle,

probably of ~15mm focal length at which it’s not hard to get a wide field and

good E.R. (of about the focal length) in a compact format.

So, Nikon claim 15.4mm for the eye relief, but out-of-the-box

that’s completely and bizarrely irrelevant. Why? Because these come with

strange hard plastic eyecups that stand a centimetre proud of the eye lenses

and carry the optional horned eye cups, which I assume is how Nikon expect

these to be used because there is no obvious alternative.

Configured like that they work well for bare-eyed viewing,

but specs wearers are just not catered for at all. This is especially strange

because the eye relief from the glass is good and Nikon even mention it in

their own blurb.

The only way to get around this limitation is to remove the

eyecups completely, but then you’re resting your specs on bare metal,

guaranteeing scratches on your Ray Bans.

Fortunately, if you want to use the 18x70s with specs, there

is an easy fix! Just

buy a pair of the Tele Vue eye guards for their smaller Panoptic eyepieces.

These are a perfect fit and an ideal solution for me. Folded down, they leave a

shallow rubber lip and give good eye relief of ~15mm for glasses. Note that

you’ll need to ask your Tele Vue dealer for these and they won’t be cheap – I

was quoted £12 ea.

Nikon’s hard eye

cups, as supplied, are useless for specs.

The horned cups

fit onto the hard ones and are a quality item made of thick rubber, work to

shield stray light.

Tele Vue Panoptic

eye cups, here shown extended (see above for images with them folded back).

Accessories

The whole series of Nikon binoculars in this style get

magnificent Japanese-made cases of thick black leather lined with velvet and

standing on little feet, yes even the cheap 7x50 Tropical model.

I loved this style of case with the Prostars;

a little less here because the bino’s are held in by a Velcro strap that

constantly snags and catches on the velvet, making the bino’s quite hard to put

away. The Prostars’ anchor-strap was elasticated in

place of the Velcro and gave no such problems.

The 18x70s get (big!) individual objective caps, much like

the ones supplied with an original pair of Nikon Es. There is, puzzlingly, no

eyepiece cap.

The strap is a nice, part-leather item, but otherwise

conventional. It looks a bit flimsy for such big bino’s, but is well up to

their weight in practice.

As I said, they come with those strange hard plastic eyecups

onto which a pair of winged eye-guards, to prevent peripheral stray light, can

be attached. On this pair, factory sealed, no alternatives were provided (see

above).

The tripod adapter clamps the central hinge between shaped

Delrin blocks that tighten down with a big knurled knob. It’s a beautifully

made accessory that inexplicably costs about four times the price here that it does

in Japan. Whatever it costs, I’m not a fan.

It does basically work, but attaching the bino’s is too

fiddly and it’s too easy to scratch the leather on the sharp Delrin edges doing

so. Once you’ve got them into the clamp, it doesn’t hold them solidly enough

unless you really screw it down hard, in which case you risk damaging the

thread.

Note: no eyepiece caps are supplied.

Tripod adapter is beautifully made, but fiddly to fit and it

would be all too easy to mar the bino’s doing so.

In Use – Daytime

Ergonomics and Handling

These seem and are huge, but I didn’t find them as hard to

hold as I expected. It’s possible to hold them around the prisms, but I always

hold them right behind the objectives to reduce shakes. I found (and so did my

daughter) that something about the weight and the way you hold these make them way

steadier than you think possible.

Sitting in an armchair to watch the Moon through the window

(see below), I rested my elbows on the chair arms and got a very steady hold.

Disconcertingly, the only real jiggles then came with every heartbeat.

Eyepiece comfort with the Tele Vue eyecups is pretty good.

With glasses on there is enough eye relief to see most of the field; without

specs, it’s a comfortable view with the cups extended and with minimal

blackouts.

These look crazy-big hanging around your neck, but actually

they’re comfortably wearable for observing sessions of an hour or two and are

holdable for a minute or two at a time.

Classic looks and beautiful build quality mean these big

Nikons look good in a domestic setting, arguably better than an armoured scope

like Swarovski’s ‘Interior’ model.

Just like

binoculars... only (much) bigger.

Nikon 18x70s

blend well in a domestic setting, would be great for watching the boats come

and go from your clifftop cottage...

The View

I had expected such a poor daytime view that I almost omitted

this section. Which just goes to show how wrong you can be.

The daytime view is fabulous, with unrivalled clarity,

sharpness and resolution in a big-eye design. Most surprising of all is

brightness. Most big-eye binoculars are a bit dimmer by day because your pupil

stops them down to maybe 20-30mm and their optics transmit a lower percentage

of the incident light. But these are bright like a pair of Swarovski Habicht porros.

These remind me afresh just how good a really finely made porro prism binocular can be – the problem with most is

manufacturing quality, not the design.

I curl up in my favourite armchair and watch a Great Tit

messing about and preening in the hedge ... 200m away. He’s literally so tiny

and so distant I can’t see him at all with the naked eye.

The main problem is lateral colour from the eyepieces, which

is distracting if your move your eyes around views of branches or birds on the

wing.

Flat field?

Field

flatteners or not, these are not a flat field binocular like a modern Swarovski SLC, let alone an EL or

NL Pure or even Nikon’s own defunct SE porros. From

about 70% the field softens until it’s very blurred by the edge, mainly due to

field curvature. You can see this in the image below, where infinity is

in-focus centre field, < 100m away at the edge.

But

here’s the thing – the apparent field is very wide by binocular standards at

over 64°. That

means a 4° true field which is more than either Canon’s

18x50s and Vortex’s 18x50 UHD Razors, both of which have 3.7°.

In other

words, the well-corrected part of the big Nikons’ field is not that much worse

than those much more modern designs, but the extra context gives an airier feel

I like.

Chromatic Aberration

These do

have significant false colour under conditions of very high brightness and/or

contrast. Most of it is from the eyepieces off-axis and can be reduced by

careful eye positioning, but there is some from the simple achromatic doublet objectives

too. Consequently, these big Nikons

wouldn’t be my first choice for birds in high branches (or perhaps aircraft

spotting), or other very high contrast use cases.

This

snap perfectly illustrates the off-axis aberrations: field curvature, not

astigmatism.

Like a

fine scope, centre field sharpness and resolution is here limited by seeing,

not the optics.

In Use – Dusk

The main problem for dusk use is getting focused in low

light. But I found them great for scanning distant (200m plus) tree-tops at

night, searching for my very noisy (especially when it’s clear) but elusive

local Tawny owls.

In Use – Observing the Night Sky

Yes, I know, most people put

binoculars this big on a tripod. Although

I do use them on a tripod for astronomy occasionally, I only find it

comfortable for objects at lowish altitude.

Mostly, I still prefer the

immediacy of hand-holding: just walking about my dark-sky garden and lane,

looking for targets of opportunity – a small open cluster in Cassiopeia here, a

galaxy with an NGC number in Leo there.

I find

it quite possible to hand hold them. Yes, I rest on the car roof, or against a

wall, for extra support if I can. Yes, they do get tiring after a while and I

have to take regular short breaks. But the benefits outweigh the inconvenience,

for me at least.

Benefits?

They just reveal far more in the way of fainter stars and DSOs and reveal far

more detail too.

Stars,

even the brightest, are especially pinpoint on-axis due to the excellent porro optics. That and the extra aperture mean star colours

really stand out in a way they don’t with smaller bino’s.

Field

curvature does distort stars in the outer third of the field, but it’s a wide

apparent field anyway so this isn’t a problem for me. Personally, I prefer a

wide apparent field with some edge distortion than a narrow one without.

One

disadvantage, more even than weight for me, is one I found on the similar Prostars: the thin leatherette and chunky aluminium body

suck the warmth out of my hands and they become painful and start going numb

after 30-40 mins on a cold night.

The Moon

A full Moon

generated only the dimmest of off-axis ghosts in field, as good as the very

best Alpha birding bino’s. But a full Moon was dazzlingly, unpleasantly bright

and also produced some significant false colour – proper purple and green in

focus – around the limb.

But then,

late one night, I saw a waning gibbous Moon rising above my neighbour’s chimney

pot and shining through my kitchen window. So whilst my family were bumping

around getting ready for bed, I pulled up an armchair and settled in for the

most relaxing and comfortable view of the Moon ever. And I saw loads. Mare Nectaris on the terminator, with Theophillus and Catherina,

small deep and shadow-filled Mädler, lava-filled Fracastorius; huge Janssen in the far south; Posidonius in

the north, along with philosopher Aristoteles and fellow Greek astronomer Eudoxus.

Absolute

sharpness and scope levels of detail and resolution made the magnification seem

much higher than it is when viewing with both eyes. Arms resting on the chair

and completely relaxed, I could easily find everything in my day-by-day lunar

atlas.

Venus

Brilliant

and high in a dark sky, a small (12.5” across) gibbous Venus at magnitude -4 showed

as a dazzling point. There was a little flare, but no spikes or significant

ghosts.

Mars

Receding

from opposition, Mars showed a minute disk at 8” across – clearly not a star

and with no nasty spiking or flare.

Jupiter

Jupiter

was bright and white enough to draw out a little false colour, but otherwise

showed a perfect, flare-free disk too. But as for almost all binoculars, I

couldn’t see much in the way of cloud belts, at least not hand-held. Making out

the Galilean moons is super-easy at this power, even when close in.

Saturn

The big

aperture pulled out more of Saturn’s characteristic cream-pink hue alongside

whiter Jupiter in the evening sky as both rose over the bay. Like most good

high-power binoculars, the 18x70s showed Saturn as a tiny flying saucer, but

with no separation of rings from planet.

Note: I

will re-visit the planets with the 18x70s mounted and steady when I’m able.

Bliss:

Nikon’s 18x70s and a clear (fairly) dark sky.

Deep Sky

If

you’re used to ‘ordinary’ binoculars, these are an absolute revelation on deep

sky and are the most spectacular hand-held deep sky bino’s I have ever tested.

M42 showed structure in the inner part of the nebula, even

saturated by the light of a full Moon. On a dark night, views of the nebula

were really stunning, better than a 70mm telescope: bright and sweeping arms of

nebulosity in the main nebula, but lots of nebulosity in other parts of the

sword region too. The Trapezium split easily, even hand-held.

You start to find nebulosity all over with these: the Heart

and Soul, the Rosette, the region below M38 in Auriga.

Smaller DSOs are just so much easier to find. The Crab Nebula

usually requires some orientation and averted vision. But with these it’s immediately

obvious, standing out from the background, big and bright and showing off its

characteristic shape.

The clusters cutting up across Auriga – M35, M37, M36 and M38

– appear as they would through a telescope, properly resolved into sprays of

stars and revealing arms and sweeps of stars in M36 (the Pinwheel) and M38’s

arrow-shape. M37 resolved into a dense nest of fainter stars where it just

looks like a misty patch in birding bino’s: perhaps the most beautiful of the

lot now, where it’s the least so with 10x42s. M35 looked big and bright and

stuffed with stars.

Views of the Pleiades are different from ‘normal’ binoculars’

too - the brilliant glittering blue pinpoints embedded in bluish mist that you

usually only see in a 3-4” refractor telescope and a really beautiful view you

just want to keep looking at (until your arms give out!)

Across in Cancer, little open cluster M67 below Praesepe looks like M35 does through a pair of 10x50s – big

and bright and full of resolved stars. Meanwhile the Beehive itself is another

magnificent burst of stars, far more impressive than through smaller bino’s.

The Double Cluster is spectacular, again much more so than usual.

Panning across into Cassiopeia, I immediately understood why folks call NGC 467

the Owl Cluster: two bright ‘eyes’, extended ‘wings’; starry body and ‘feet’

too. Cassiopeia contains numerous other, smaller clusters that the 18x70s will

easily resolve.

These are the best hand-helds I’ve

ever used for finding galaxies. I found M51 and M101 either side of Alkaid with

absurd ease; M106 soon followed. Across in Leo, M105 and M95 are big and

bright.

Binocular doubles are another enjoyable use case for the

18x70s. Cor Caroli is a beautiful easy split at 19.3”.

The 18x70s

are the most capable hand-held astronomy binoculars I’ve tested. They’re real

deep-sky specialists. The only problem is they make me resent every trace of

light pollution.

Summary

If I had

to single out one best astronomy purchase in recent years it would be these

Nikon 18x70s. I’d read conflicting reports on the forums and wasn’t sure if I’d

like them. Well, I do. In fact, I find them so addictively good for what I like

– hand-held deep sky – that on dark clear nights I’m drawn to them at the

expense of my scopes and cameras.

Truthfully,

they are not perfect. By day they are bright, pin-sharp and offer huge

resolution. They even have a wide field, but they do suffer a bit of field

curvature and minor astigmatism off-axis. Those individual-focusing eyepieces

are a nuisance, unless you’re viewing something static. But these are not dim

and unsharp as some high-power bino’s are. Neither, surprisingly, are they

difficult to hold steady for short periods.

No, the

Achilles’ Heel of the 18x70s in the daytime is off-axis colour from the

eyepieces, which is troubling and distracting when moving your eyes about the

view, but only in high-contrast situations. In ‘normal’ use these do give a fabulous daytime view.

But for

astronomy, views of stars, nebulae, clusters and assorted DSOs and even the

Moon, are just so good, even hand-held. For those things they make even the

very best ordinary binoculars seem, well, almost boring by comparison. It’s the

immediacy and immersion of bino’s with the reach and power and resolution of a

telescope and I love it.

The

icing on the cake is their simple, rugged, heirloom-quality Japanese build. If

you look after them, they should give a lifetime – literally – of magnificent

deep-sky views.

If you like hand-held deep-sky astronomy with binoculars you’ll

love these Nikon 18x70s. They get my highest recommendation. For terrestrial

use they do give remarkable high-mag’ views, but with too much lateral false

colour in high contrast situations.