A Visit

to Mount Palomar Observatory

Pretty much each and every astronomy or space book on my

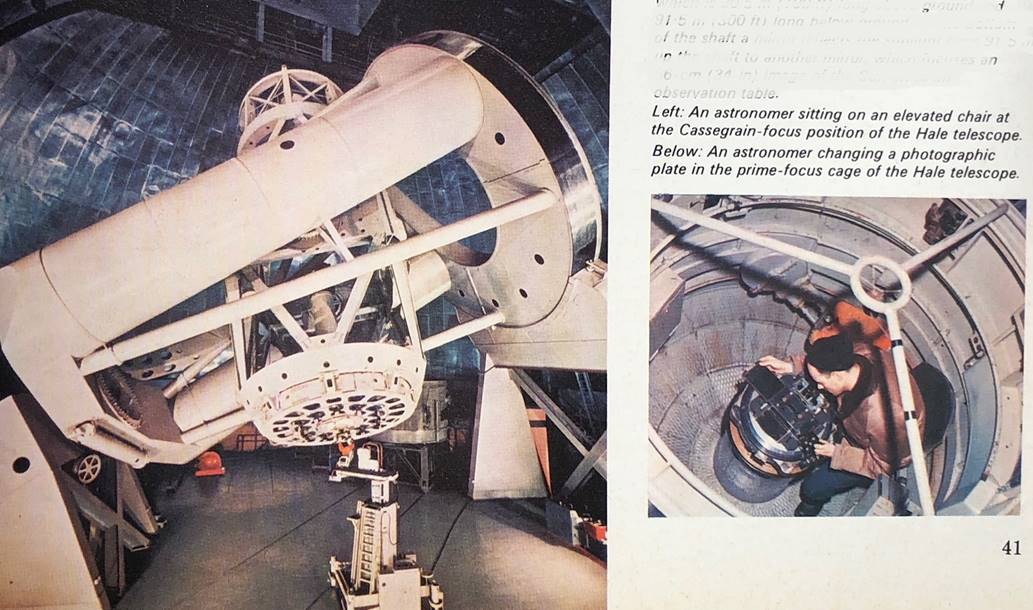

bookshelf once had an image of the 200” Hale reflector at Mount Palomar in

California (see last photo below). Not only was it a photogenic marvel of

(then) modern engineering; the 200” was also for decades the largest optical

telescope in the world, doubling the size of the previous record-holder, the

100” Hooker reflector on Mount Wilson.

Incredibly, despite the project starting in 1928 and seeing

first light in 1948, the 200” (5m) Hale remained the largest optical telescope

of any kind until 1976 and was only really surpassed when the 10m Keck 1

telescope on Mauna Kea, with its revolutionary segmented mirror, became

operational in 1993.

The Russian BTA-6 (Big Alt-azimuth Telescope) theoretically

surpassed the 200” in 1976 with an aperture of 240” (6m), but neither its

optics nor its location ever really worked well enough for it to supersede the

giant Hale reflector on Mount Palomar. So the 200”

Hale arguably remains the largest telescope ever with a *fully functional*

monolithic mirror and the largest Classical Cassegrain of all time.

Surprisingly, though it is over seventy years old, the 200”

Hale remains operational, still a very useful size for professional work even

today. So, unlike the historic 60” and 100” instruments at Mount Wilson, it has

never retired from professional use and still does research.

The road to Mount Palomar

Palomar visitor centre

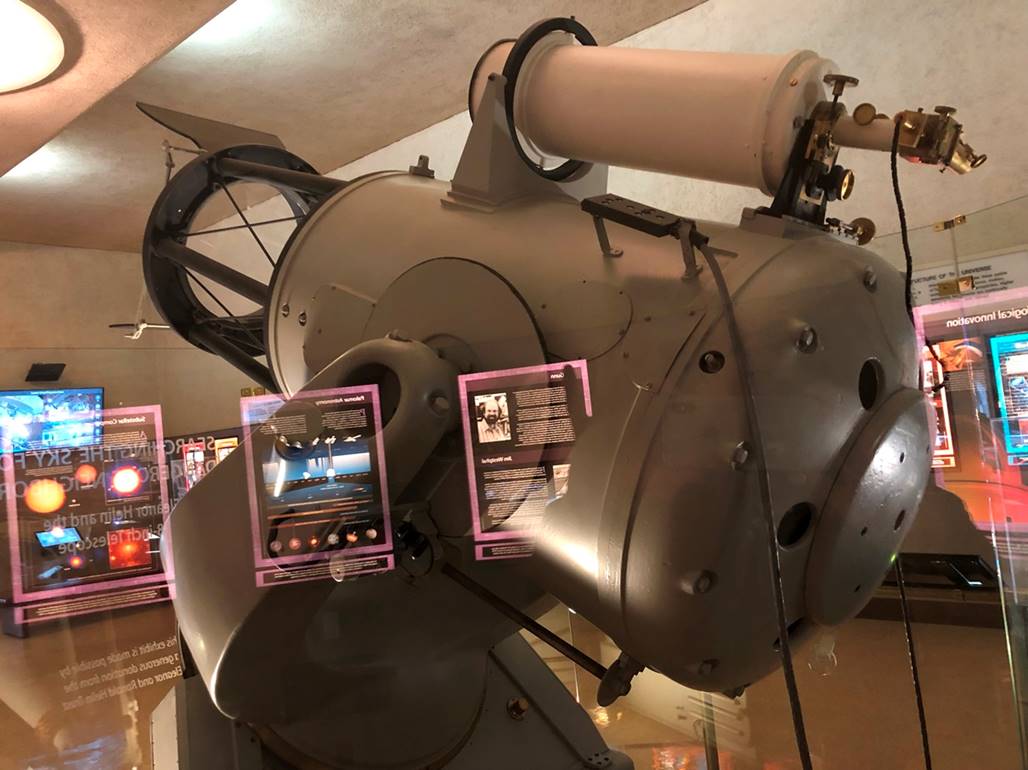

Palomar’s original 18” Schmidt camera, now in the visitor

centre

Planning a visit

Considering that it lies smack between the conurbations of

greater Los Angeles, San Diego and Palm Springs, the Palomar observatory is in

a remote spot. Even so, it is easily accessible as a day trip. I approached it

from the Pacific, having stopped in the pretty seaside resort of Oceanside

(home to OptCorp, a well-known telescope shop).

Highway 76 from Oceanside starts off as a wide divided

highway, but soon narrows and curves into the hills. After about an hour of

driving (even in my rental Mustang) and some forty miles, the turn-off to Mount

Palomar is an easy-to-miss junction on the left named South Grade Road or ‘S6’.

It immediately passes Oak Knoll Campground and acquires a 30mph speed limit,

which seems odd until you start driving it. The bends come so thick and fast

and are so ferociously steep and writhing, that indeed 30mph is about all I can

manage in the Mustang anyway.

After an eternity of sawing at the wheel, around hairpin

after tyre-shredding hairpin, you arrive at a junction. It would be easy to

take a wrong turn here. Ignoring East Grade Road on the right, you continue a

short way on the main road, which then veers off left towards the resort of

Palomar Mountain. Instead of following it, carry straight on S6 for another 5

(much easier and less bendy) miles through forest to the observatory.

I had set off chipper and top down from a sunny and balmy

beach in late May. But by the time I arrived on Mount Palomar, I was surrounded

by fog and fresh snow and the temperature was only just above freezing. Come

prepared for un-Californian cold, even in summer.

You can park at the observatory and just wander around; there

is no entrance fee and you don’t need to book a tour. There is a small visitor

centre, but the main event is of course the 200” Hale and its huge dome. The

dome appears to be open most days, but tours are

infrequent.

What to see

The building nearest the car park is the visitor centre. It

hosts various displays on the construction of the Hale and its many

discoveries. For scope fans, it also houses the observatory’s original

instrument, a beautifully made (by Mount Wilson and Caltech) 18” Schmidt

camera. The Schmidt camera was a cutting-edge design when it was commissioned

in 1936 and used for hunting supernovae. On its compact fork mount, it still looks

quite modern apart from a few brass fittings, reminiscent of a big Meade or Celestron SCT I thought.

The 200” dome is a longish walk through the pines. Built

between 1936 and 1939 (a decade before the telescope was ready), it’s a truly

huge building (the thousand-ton dome is reportedly similar in size to Rome’s

Pantheon) and like the visitor centre has a distinctly pre-war streamlined Art

Deco aesthetic, like the Hale reflector itself. On the day I went, it

disappeared up into cloud, still sprinkled with melting snow. The dome’s

external steel plates were originally painted silver, but are brilliant white

now.

Up four flights of steps, you reach an oak door into an

elegant marble atrium complete with a bust of George Ellery Hale, who sourced

much of the funding and led the project. Another sweeping staircase on the left

leads up to the observing floor.

Since it is still a working professional instrument, you

can’t get to the telescope but you can admire it from a glass-walled corridor.

The cavernous space is dimly lit, the telescope and its mount enormous,

reaching high into the gloom towards the glinting aluminium inner panels of the

dome roof.

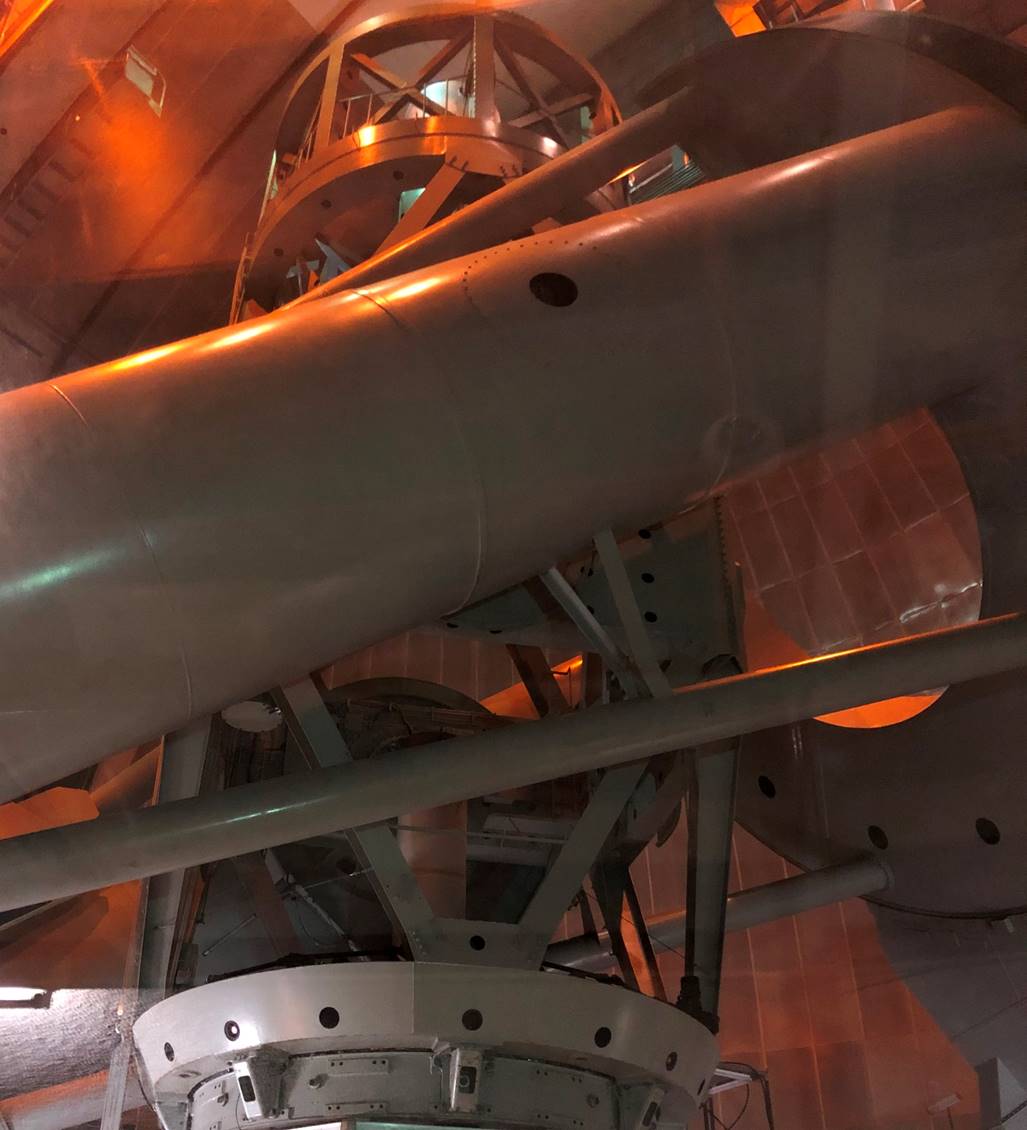

Unlike the fussy rivets and girders of the Hooker, the

previous largest telescope, the 200” Hale and its huge yoke mount have smooth

and simple lines, a piece of 1930s ‘Streamlined Moderne’

architecture finished in polished light grey paint. The yoke mount comprises

just two giant tubes with four additional truss tubes and a giant horseshoe-shaped

bearing at one end, a regular bearing at the other. The optical tube assembly

is simple with just a few thick trusses instead of lots of smaller ones: the

most elegant of professional telescopes.

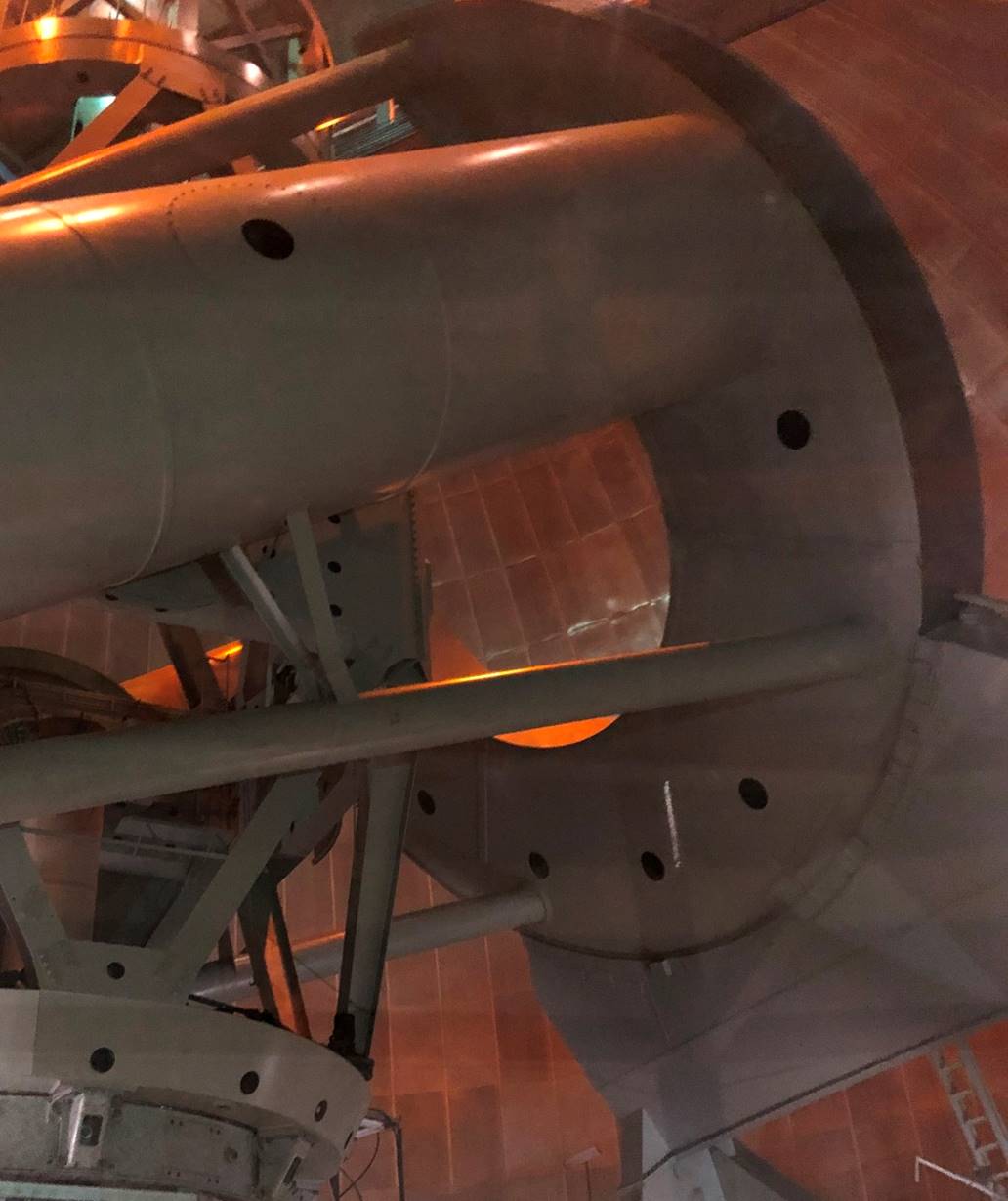

The tube is parked vertically and a large instrument package

is attached below the 14.5 ton parabolic primary

mirror at the F16 Cassegrain focus (the 200” Hale is the last big telescope of Classical

Cassegrain optical design with a slow focal ratio of F16). Those instruments

include several cameras, optical and infra-red, and three different

spectrographs. At the very top of the tube is cylindrical secondary mirror

housing, large enough to have once housed a plate camera at the F3.3 prime

focus.

Bottles of gas stand nearby to cool the sensors, yellow

ladders and a cherry-picker to service the instruments. The whole has that

clean, sparse and industrial look typical of a modern professional observatory where

the telescope is operated remotely from a control room – no photos, books or

star maps, mahogany desk or captain’s chair here.

Whilst the 200” Hale is Palomar’s star attraction, it does

have several other working instruments, including a 48” Schmidt camera and a 1970s

60” reflector, mainly used robotically by CalTech for

sky-survey follow-ups and instrument testing. These instruments weren’t open to

the public on the day of my visit.

Simple, clean lines of the truss-tube and mount

Hale prime focus cage

Detail of the modern instrument package at the Cassegrain

focus, comprising various cameras and spectrographs

South and north bearings of the huge yoke mount: scope and

mount weigh 530 tons in all

Tidy, industrial-looking observatory floor

The Hale 200” as it was in the 1960s, from an old astronomy

book

Summary: Compared to some historic observatories, both access

and interpretation are a little sparse at Palomar. Still, seeing the truly-iconic

200” and its dome are a thrill for any fan of astronomy and its history. Mount

Palomar certainly makes a worthwhile day-trip from southern California.