Questar

3.5 Review

“What possible use it that!

What use is that to anybody?!”

I suffered similar questions from a passer-by when I took my

Questar to a star party a few years ago. But this time it was the response my

daughter got when she announced she was taking Latin GCSE.

The discussion started at a Guides meeting, a change from the

usual topic of boyfriends. When other girls announced their free GCSE choices -

drama, art, photography, R.E. and P.E. - the Guide Leader was approving. So it’s

hard to understand why my daughter’s choice was singled out for crushing.

OK, Latin doesn’t have the kind of immediate vocational value

of computer programming or bricklaying, but neither, I’d argue, do Art or P.E.;

nor for that matter History or Geography.

The real problem, I suspect, is that

the Guide Leader saw Latin as Elitist.

It’s the same for Questar. And just like Latin, the Questar turns out to be a

much more useful tool than you might think ... but I’m getting ahead of myself.

Top of the pile, or elitist anachronism?

Instead of banging on about Larry Braymer and all the usual

historical stuff (check out the Company 7 website for all the history on

Questar), I’ll tell you how I first met the Questar because it’s probably the

same way you did.

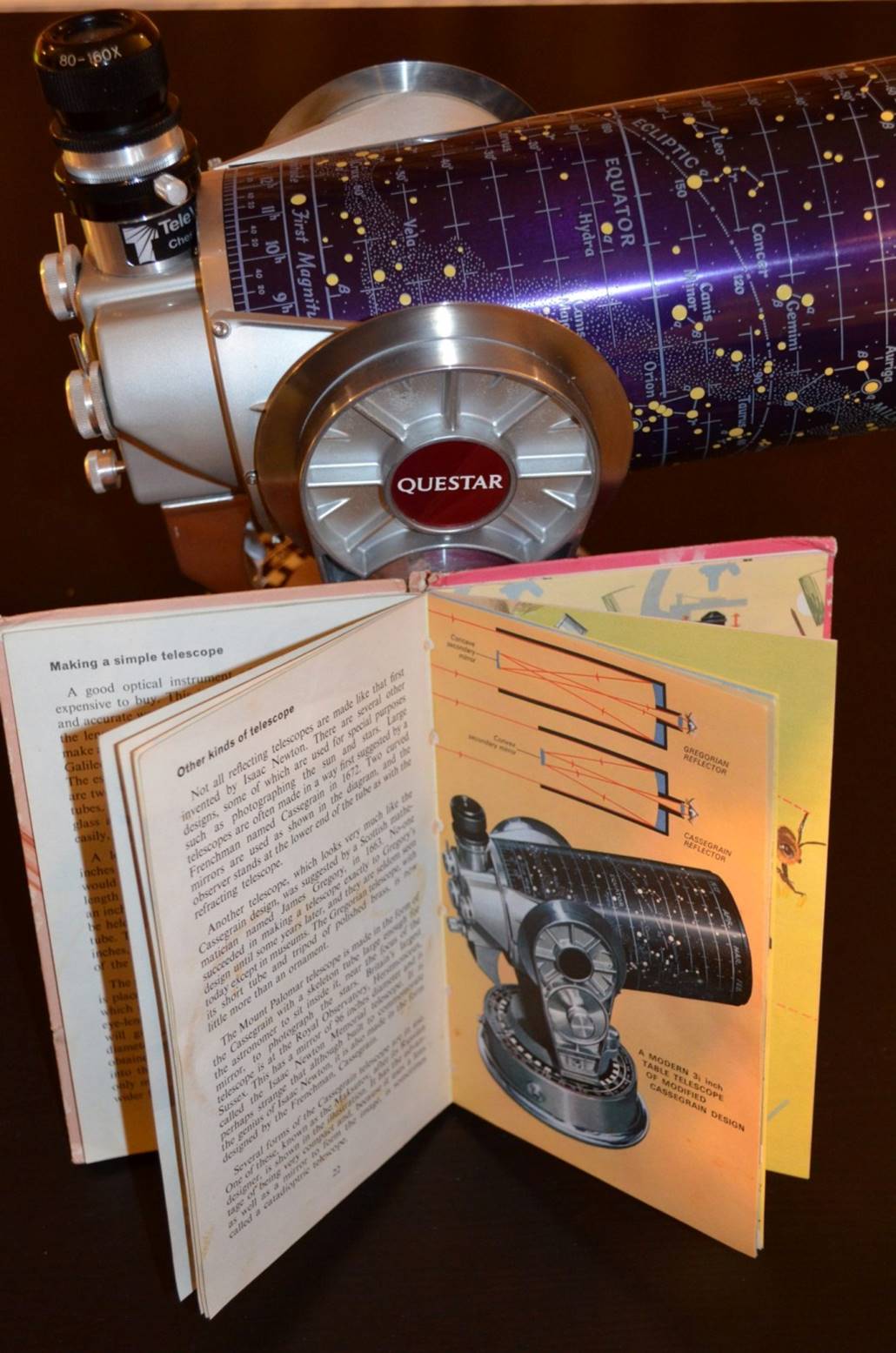

See, I didn’t even know it was a Questar, all I knew

aged 8 was that the illustration in my Ladybird Book of the Telescope was

something special. The painting was of a tiny, Faberge-egg of a telescope with

a star map for a barrel and all sort of tiny controls on the back. It looked

nothing like the telescopes I used to drool over in the local camera shop on

Saturday mornings and was ... even to my young eyes ... clearly superior.

When my early telescopes didn’t come up to scratch – dim

optics, wobbly mounts, drives that didn’t – I used to look again at that

Questar in the Ladybird Book and think about the amazing views it would surely

give.

So was the Questar really

superior? And even if it was superior then, how does it stack up today (OK,

enough book puns)?

The illustration that introduced me to Questar

At

A Glance

|

Telescope |

Questar

Standard, Duplex |

|

Aperture |

90mm

(3.5”) |

|

Focal

Length |

1280mm |

|

Focal

Ratio |

F14.2 |

|

Central

Obstruction (incl. holder/baffle) |

~ 33% |

|

Length |

~ 27cm |

|

Weight |

~ 3.5 Kg |

Data from Me/Questar, vary depending on

exact model

Design and Build

It’s worth saying at the start - both new and classic

Questars are beautiful objects, with an almost sculptural quality that must be

unique in astro’ gear. The Questar is a design classic that you could almost

put on a marble column in an art museum. Someone somewhere probably has.

The Questar has unmatched nostalgia value. Arthur C Clarke

owned one, Werner Von Braun too.

But this is a scope review, not an essay on aesthetics, so we

need to get past the Questar’s obvious visual appeal and classic status, get to

grips with its numerous unique features.

Standard or Duplex,

Birder or Field?

The Astronomical Questar is essentially just a small

Maksutov in a fork mount. The original Questar (like mine) is known as the

“Standard” model. It has the OTA and fork as a unit.

The Duplex has a detachable OTA – unscrew a knurled

knob underneath and the OTA comes away so that it can be mounted on a photo

tripod.

The Field model is essentially just the Duplex OTA

without the Moon and Star maps on the barrel and Dew-shield. It makes a very compact

and light-weight high-magnification terrestrial scope.

The Birder is similar to the Field model, but with

these key differences:

·

A

faster focusing mechanism.

·

A

larger built-in finder (all Questars have a finder scope built in, but in the

birder it’s a proper little spotting scope in its own right).

·

Clip-on

end caps that are easier to get on and off than the Standard’s metal screw-fit

one.

Various other Questar variants exist and come up for sale on

Ebay: these are typically specialist defence or industrial products like

long-distance microscopes or fibre-optic ‘bridge’ components. Don’t assume

these are readily convertible to astro’ use (though they might be!).

The OTA

easily detaches on A Duplex to leave you with a tiny spotting scope.

Questar

Duplex OTA alongside one of the smallest APOs – a Takahashi FS60.

Questar’s

broadband coatings are an excellent, but expensive option.

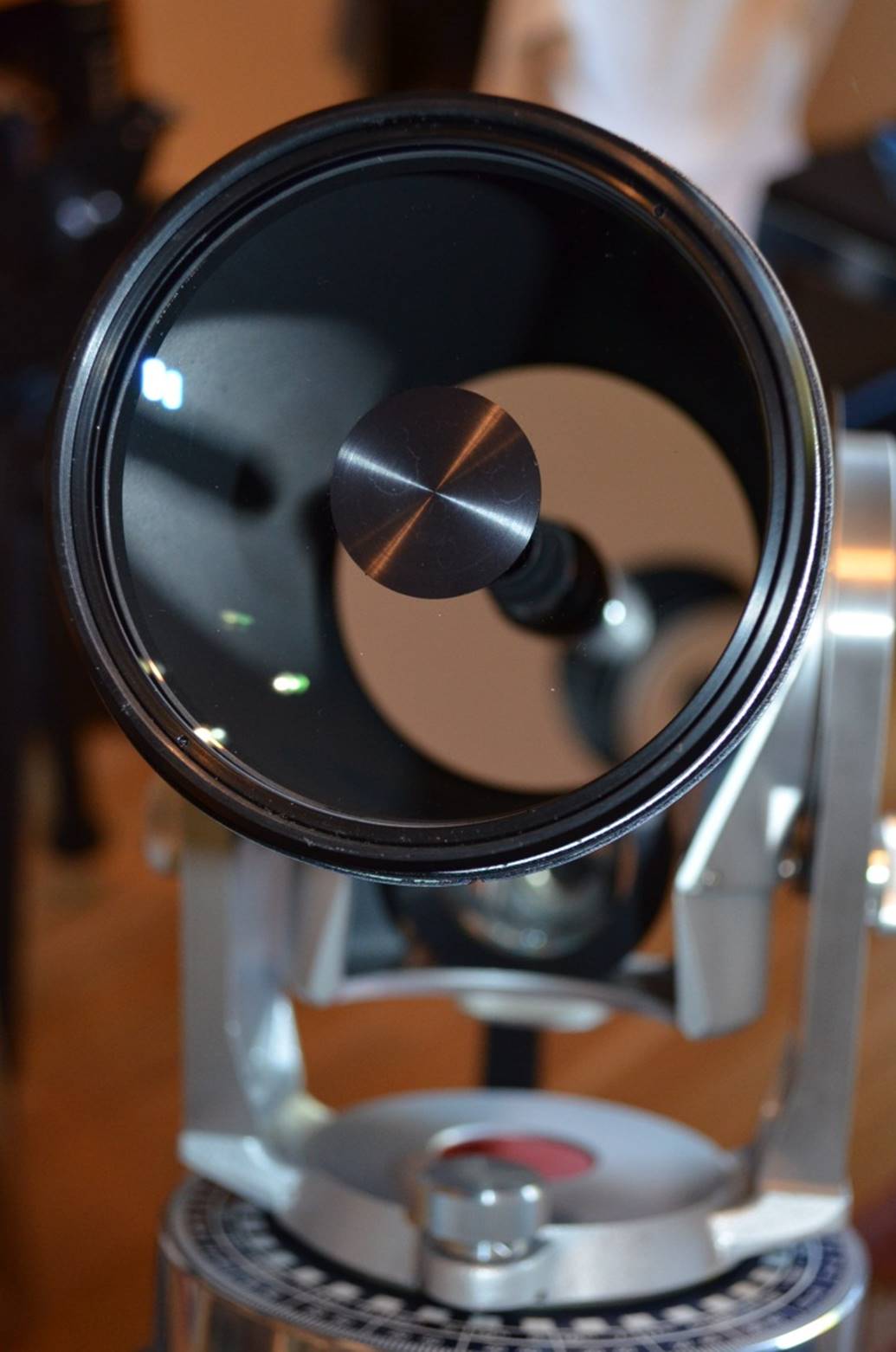

Optics

Fifty years ago, the Questar’s optics must have been quite

revolutionary on a personal telescope, but these days they are on the face of

it pretty standard stuff – a 90mm F14.2 (1280mm) Gregory Maksutov with moving

mirror focusing. So the Questar is a type of Cassegrain with a thick corrector

plate at the front and the secondary mirror as a fixed silvered spot on the

back of the corrector. So optically it is the same design as the many other

small Maksutovs on sale (the other type of Maksutov is the “Rumak” which has a

separate secondary mirror like an SCT).

Unlike most other 90mm Gregory Maks, though, the Questar has

high optical quality pretty much guaranteed. The standard mirror is Pyrex and

has a very good figure (from a local optical fabricator) to allow high

magnifications, but if you want to go further you can specify various optical

options:

·

Broadband

coatings - just very transmissive multi-coatings. The Duplex in this review has these coatings.

·

Zerodur

for the main mirror - a special glass which doesn’t expand or contract much

with changes in temperature and so makes cool-down more benign and may work

better for Solar viewing. The Duplex in

this review has a Zerodur mirror.

·

Quartz

for the mirror. Quartz has similar thermal properties to Zerodur, but can be

polished to an even finer figure. Quartz Questars are guaranteed to tenth-wave

PV and come with a Zygo report to prove it. Yum!

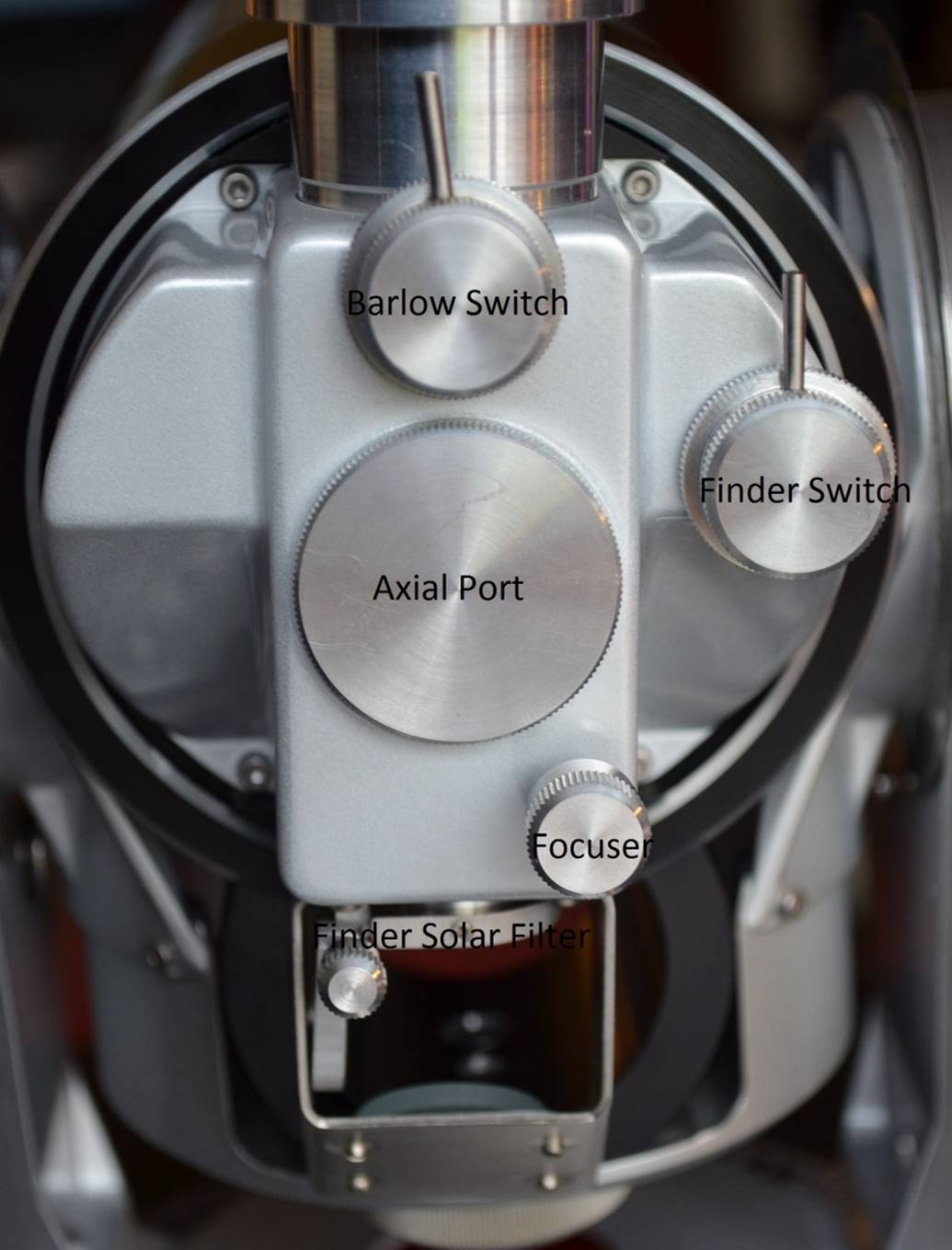

The Control Box

The Questar control box is a big part of what makes a Questar

special. It’s a much copied feature – all Meade ETXs have something a bit like

it – but the copies all seem to miss out the important bits.

The control box is the unit at the rear of the OTA with

various small wheels and levers on it. I’m told it contains 120 moving parts.

On a modern Questar it includes the following controls:

·

A

small focuser knob.

·

A

lever to switch the eyepiece view between the main optics and the finder.

·

A

lever to switch in a 2x Barlow lens contained within the control box (thus

handily doubling the magnification of whatever EP you’re using without swapping

components around).

·

Another

small knob to flip in a Solar filter over the objective of the finder (older

models like my Standard don’t have this).

The control box also

contains the diagonal prism and eyepiece holder and has a port for

straight-though viewing or attachment of a camera (adapter required). On the

bottom of the control box is the finder objective – a tiny (~10mm) lens that

points downwards and views via a small mirror set on a mount that protrudes

underneath the box.

If this all sounds like a complicated recipe for faults and

problems, know that mine is 50 years old, has had a lot of use and still works

every bit as well as the recent Questars in this test.

Finder

A built-in finder is one of Questar’s features (and one the

copiers at Meade and Vixen always leave out). It’s part of the Control Box (see

previous section) and is just a tiny refractor built vertically into the bottom

of the box; a right-angle mirror on a ‘scoop’ arrangement then pulls in the

view parallel to the main OTA. You swap the view through the eyepiece between

finder and main optics using a switch.

The advantage of this system is that it’s completely

intuitive, but the finder magnification and field does of course vary with the

eyepiece you have installed.

If you have a modern Questar the finder incorporates a

switchable Solar filter, which is a great idea. Conversely the older Questar is a bit dangerous because if you’re observing the Sun

and you accidentally knock the finder switch, you’ll blind yourself.

Fork Mount

The Questar fork mount is a clever piece of engineering. Not

only does it incorporate RA drive and manual slow motion controls on both axes,

but you can push it around like a Dob’ as well (and all without loosening a

clamp or disengaging the drive).

The final convenience feature is the ability to rotate the

OTA to get a comfortable eyepiece position. This works superbly, but note that

the range of rotation is more limited if you use an adapter for regular

eyepieces (either the Questar or Tele Vue varieties) and at more extreme angles

the finder may be obstructed (particularly in a duplex).

The basic fork unit can simply be used on a table in alt-az’

mode, or you can fit three supplied legs to make it into a table-top

equatorial. Alternatively, you can use the ¼-20 threaded hole on the base to

mount it to Questar’s own pier (see below) or any robust photo tripod.

Drive Options

My old Standard has RA motor drive built into the base. Just

connect up the mains lead and it ticks away. Modern Questars get the same

arrangement by default.

If you want something more flexible and portable you’ll be

needing the Powerguide, of which at least two variants exist and which can be

fitted later as an upgrade (but not in my case – literally because it would

make the Questar too tall to fit it’s leather carry case).

The original Powerguide I uses a battery in the base of the

Questar, whilst the Powerguide II contains a small 9 volt battery in the hand

controller. In either case, it’s a convenient solution: you no longer need

mains power or a separate battery pack. What’s more, there is just a single

lead with a phone-type (RJ11?) jack hidden on the Questar’s base (don’t want to

spoil those sleek lines do we?)

The Powerguide controller just provides basic options – there

is no fast slewing (let alone GOTO), but you can control a separate declination

motor that is a clip-on optional extra.

Apparently Questar did consider GOTO at one time, but very

wisely decided to keep it simple. If I have a criticism of Powerguide, it’s not

the simplicity, but the plastic hand controller. Questar should take a look at

the classy cast unit for a Takahashi EM200.

Questar

Duplex in table-top mode.

The classic leather

case (right) is too short to accept a Powerguide conversion.

Powerguide I

Powerguide

II

Tristand and Astro-Pier

The Tristand and Astro Pier are Questar’s dedicated supports.

Both use the same head, but the Tristand is shorter and suited to seated

viewing. It is designed to be highly portable – undo three clamps and the legs

fold up after which it balances perfectly on the provided handle.

The Tristand incorporates a rotating eyepiece tray and is

more stable and convenient than a tripod, as the legs don’t get in the way so

much. Questar and stand together are moderately heavy (about 12kg), but still

easily moved around as a unit.

The stand and head are very finely machined and engineered.

The Questar attaches to a round plate on the head via its ¼-20 thread and then

the whole assembly moves on bearing to achieve the desired latitude angle. Both

altitude and azimuth can be adjusted by micrometer controls, making polar

alignment of a mounted Questar very easy:

·

Plug

in a low power eyepiece.

·

Set

the OTA vertical in the fork legs (i.e. with the Declination circle set at 90).

·

Slacken

off the altitude clamp and azimuth set screw on the Tristand head.

·

Using

the slow motion controls on the head to bring the Pole Star into centre field.

·

Re-tighten

the clamps.

Questar

Standard model on a Tristand, ready for Solar work.

The Tristand

folds up for transport and is well balanced on its handle.

The TriStand

head is beautifully engineered.

Questar

Brandons.

Original

Questar eyepiece from 1964 and modern Tele Vue adapter.

L to R:

Modern basic case, modern leather upgrade, classic leather.

Cases

There are at

least three different cases in existence: the original leather one from the

Sixties (gorgeous but too short for a modern Q), the basic modern vinyl case

and the upgrade modern leather case.

Eyepieces

When it comes to eyepieces Questar are a bit quirky. Sixties

ones like mine had two screw-in Erfles of dubious quality and no immediate way

to fit anything else (though modern adapters will fit to allow any 1.25”

eyepiece).

Since 1971 Questars have come with two eyepieces of a special

type called the Brandon and which also screw in, but can be used in a 1.25”

barrel. Questar sell a complete set of Brandons in a wooden case if you’re

feeling like spending big. Brandons are a unique, 4-element design and are U.S.

made. Unusually, they are not

multi-coated because the maker (Vernonscope) says it reduces contrast on bright

objects like planets.

If you do want to use ordinary 1.25” EPs, you can buy

adapters from either Questar or Tele Vue that work well. But note that other

eyepieces may not focus properly with the finder.

I don’t want to pre-empt the test, but I can tell you that

although I really like Brandons as high-power planetary eyepieces, I prefer

Tele Vue Plossls for lower powers. In particular I found the 32mm Brandon to

have blackout problems (spherical aberration of the exit pupil to use the

technical term).

Some smaller (as in physically smaller, you can’t imagine

using a 17mm Ethos in a Questar) Naglers and Panoptics also work well. The 19mm

Panoptic is apparently a particular favourite amongst Questar owners. I did try

my 13mm Ethos and it worked very well indeed, but isn’t a practical option.

Maps

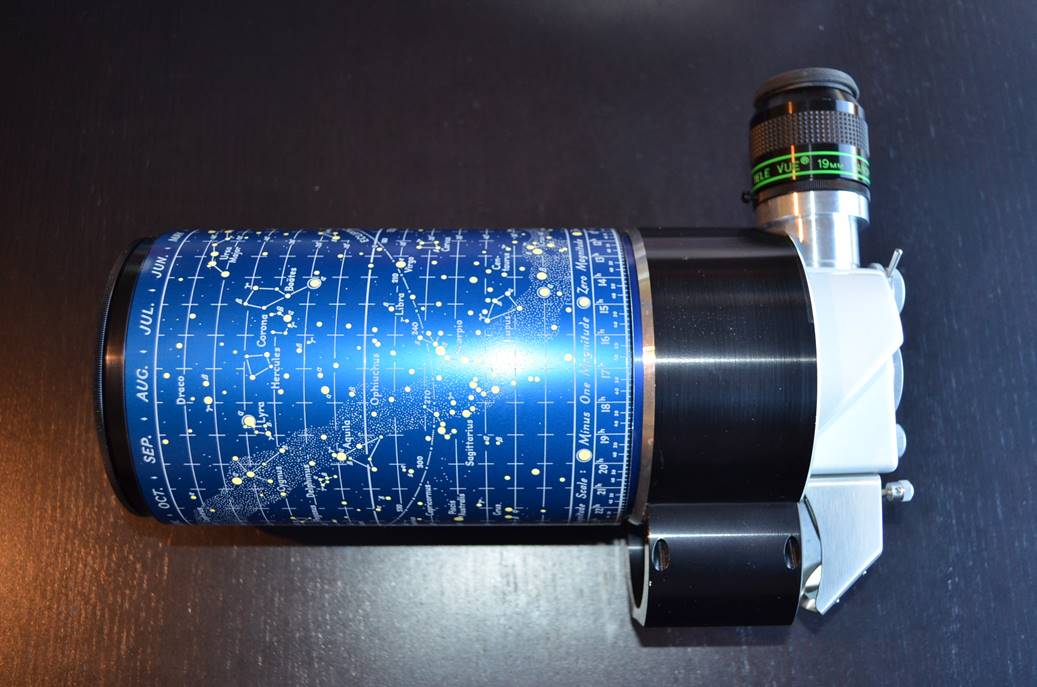

Questar astro’ models have always come with two maps on-board

– a star map on the dewshield, a Moon map on the barrel. The Duplex continues

the tradition, but the maps are a bit smaller. The maps show all the main

features, but are limited to casual use; they are beautiful though (to my tastes,

anyhow).

The original Questars (like mine) had a silk-screened star

map with a purple background; recent ones are a dark blue with the stars

printed on. I believe that the 50th Anniversary model reintroduces

the purple silk-screened map, but no one I know is rich enough to own one, so I

can’t confirm it!

Questar star

and Moon maps. Modern star map is printed on; classic was etched in.

Questars on

test: Duplex, modern Standard and 1964 Standard.

Another

superb-but-costly Questar accessory – the pulse illuminated guiding eyepiece.

In

Use – Daytime

Questar have

been selling to birders and spotters for years and with reason. The Q makes a

great terrestrial scope. Questar is capable of high powers and the image is

sharp and free from the false colour you get with all prismatic spotters. The

scope itself is light, compact, robust and easy to mount (in Duplex, Field or

Birder form).

But perhaps

the killer app with Questar for terrestrial use is the control box that

contains focuser, finder and barlow in an easy-switchable format: perfect for

use in the field with cold or gloved hands where dropping an expensive

accessory in the mud is otherwise a real possibility.

Of course,

unlike the best from Swarovski, Zeiss and Nikon, the Q isn’t waterproof and

long-term exposure to damp could cause fungus on the mirror. Most Field and

Birder models seem to end up stored in Peli cases with desiccant sachets.

We tested

the Questars alongside various other scopes, small and big!

In

Use – The Night Sky

The Three Questars

I used three Questars for this test, but have previously had

access to a recent Field model as well.

My own Questar is a 1964 Standard Model. It’s in mint

condition, but the corrector plate is slightly scratched from decades of

cleaning and dew removal by previous owners. It’s not hard to pick up Questars

like this, but be warned – if you need them fixed it’s going to be an expensive

business. I’d like to get mine serviced, but the repairs will cost more than

the scope did (though much less than a new one).

The other Questars both belong to my observing pal Ian. One

is a three-year old Duplex, the other a recent Standard Model.

The Duplex here has just about every option you can throw at

it, including the Zerodur mirror and broad-band coatings. What’s more it came

with virtually every available accessory too – Tristand, full set of Brandon

eyepieces, full set of specialist filters, full-aperture solar filter, variable

polariser, camera adapter, pulse guider, star diagonal, leather case, H-Alpha

filter, Camera adapters, the list goes on. All-in-all I think it cost its

original owner about £12000 – ouch, those accessories are expensive!

General Observing Notes

We put the Questars out on a number of nights with a wide

range of eyepieces, including a full set of Brandons, a 19mm Panoptic and

various TeleVue Plossls (which suite the Questar well).

We also had a few other scopes for comparison, all of which

cost very roughly the same as a Standard Questar when new and suitably mounted

– a Takahashi FS-78 and a Tele Vue TV-76 (both 3” APOs) and a Sky-Watcher 400P

16” Dobsonian. I thought the comparisons would be interesting, if only because

most of the sneers Questar receives are due to the perceived ‘better value’ of

other scopes.

A Questar cools slower than a 3” APO, even than the Tak’

FS-78 with its big tube, still showing a thermal plume in the star test after

the APOs had fully stabilised. However all the Questars were quite usable after

twenty minutes or so and I can’t say I found the Zerodur Duplex all that much

better than the Pyrex Standard models. Cool-down certainly isn’t a problem the

way it is with a bigger Maksutov.

The Questars are very slightly worse in poor seeing than the

three-inch APOs, as you’d expect of an obstructed aperture, showing a touch

more disturbance of the image under the same conditions.

The focusers on the Standard Questars have very little image

shift, that on the Duplex slightly more for some reason.

The Questar barlow is not parfocal (about 4 turns required)

and though it works well (and is very convenient) it can cause blackout

problems on longer F.L. eyepieces due to increased eye relief, as all Barlows

can.

I noticed how relaxing the Questar setup was to use:

·

The

built-in Questar finder is a very convenient feature: you don’t have to crane

you neck or move to use it, but it did show some ghosting when working around

the Full Moon.

·

The

easy-to-achieve perfect polar alignment means no fiddling to keep the image

centred, even at high power.

·

The

short pier legs make it easier to get comfortable and less likely that I’ll

accidentally kick the tripod and lose alignment.

·

The

eyepiece holder on the pier is at just the right height and has a convenient

tray section for my glasses.

·

The

rotating OTA allows ideal orientation of the eyepiece.

·

The

accurate focuser makes it easy to make fine adjustments when swapping EPs.

·

You

can mix RA drive, push pull and slow-motion controls without having to loosen

clamps.

·

It’s

a frosty night, but pulling out the dew-shield avoids problems, even though the

nearby Dob’s secondary is already hazing over.

·

The

built-in Barlow means less swapping eyepieces.

None of the other test scopes come

close in terms of relaxation and convenience. The Questar reminded me of observing

with my permanent setup in the dome. On the Tristand It really is a portable

observatory.

The Moon

The Questar gives excellent views of the Moon - sharp and

detailed and not blindingly bright like a big scope (the 16” Dob’ is impossible

on the Moon for this reason). However, the Brandons are too narrow of field for

my tastes. After years of using widefield designs, it’s hard to go back a

limited field for Lunar viewing; I preferred the 19mm Panoptic.

Compared to the APOs, the Questars hold up well. All can

deliver a surprising level of resolution in good seeing. The Moon is just past

full and I can enjoy scanning the promontories and bluffs around Mare Criseum

and checking out the rilles in Petavius and Janssen.

Jupiter

Once cooled, the Questars weren’t far behind and gave a very

good view of Jupiter with both 12mm and 8mm Brandons giving 104x and 156x

respectively. With the tracking and accurate focusing making it easy to get

perfect focus, several cloud belts with dark storms, the GRS and both grey-blue

polar hoods could easily be picked out. At times of good seeing there was the

hint of more detail to come – banding in the hoods, more dark and light spots

in the belts.

The Duplex gave a very similar view, but slightly brighter

thanks to its broadband coatings. My old Questar was predictably worst with a

yellowish tinge to the planet and more unfocussed light around it (probably due

to the scratched collector), but most of the main details were still easily

visible.

The Brandons may be a bit narrow of field for the Moon, but

they make ideal planetary eyepieces with good sharpness and contrast, decent

eye-relief and comfort even at shorter lengths and no problems with ghosting

that you get with some EPs on bright planets (the Nagler zooms and Tak’ LEs to

name two).

Mars

The red planet is one target on which I think the Questar

‘beat’ the FS-78. On one night with good seeing we pushed the magnification to

several hundred times on both Questar and APO. The Questar seemed to me to

deliver a bit more detail, showing impressive albedo markings and polar cap

detail for a small scope. This might have been because the Takahashi showed a

hint of false colour; usually the FS-78 is CA free, but like many APOs is less

well corrected in the red.

Mercury and Venus

The quality optics and freedom from chromatic aberration make

the Questars an excellent way to view the inner planets. Venus shows a crisp

phase with no smearing or bloating (apart from atmospheric).

We used the Questars to travel to a remote site for viewing

Mercury. The nearest planet to the Sun is small and difficult at the best of

times, but the accurate tracking (Mercury is best viewed in partial daylight,

but then disappears to the naked eye, so tracking is vital) and high-power

capabilities of the Questars made the most of it.

Deep Sky

Even with the 32mm Brandon, the Questar struggles to fit in

the whole Pleaides. The view is good, with pinpoint stars, but the APOs are

better on extended objects like clusters.

The Questar works much better for smaller Messier objects.

The Ring Nebula, the Dumbbell and M13 (a globular cluster in Hercules) all

looked as good as I’ve seen them in a small telescope, revealing excellent

light transmission and contrast. Here, the extra aperture over the 3”

refractors gives a better, brighter view win for the Questar.

Obviously the Dob’ gave vastly brighter views of DSOs, up to

the point when its secondary iced over and we put it away. But it must be said

that the Dob’ was also much less pleasurable to use overall – requiring steps

to reach the eyepiece and much precarious leaning over to use the finder.

Double Stars

I only tried Epsilon Lyrae (the ‘double double’) and Rigel,

but both split easily at 100x-156x with the Duplex, but my old Questar failed

to split Rigel.

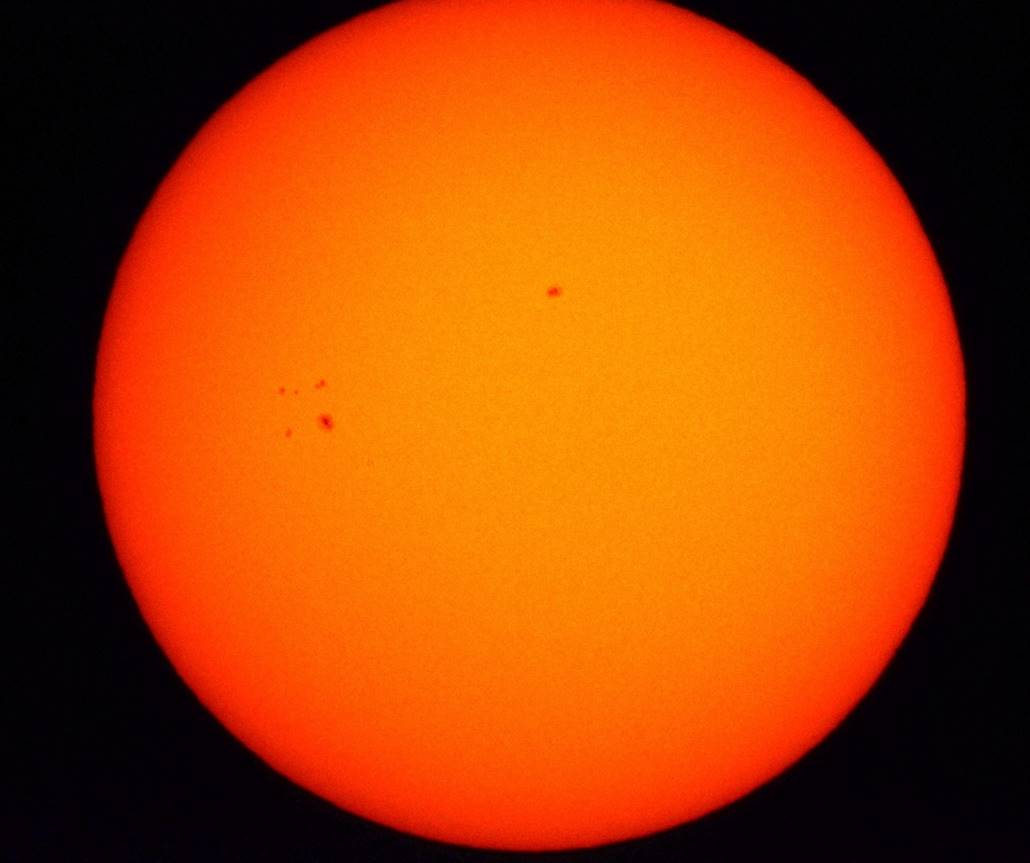

The Sun

Solar viewing is a Questar speciality. I’ve used the standard

sub-aperture solar filter for a while and it gives very good views, but the

full-aperture one (an expensive accessory) is much better for photography.

Together with the finder filter (standard on newer Questars) the solar filters

(both of which screw onto the end of the OTA) make a great way to enjoy the Sun

and are one of the areas where Questar adds value.

Narrow-passband filters (Hydrogen alpha and Calcium K) are

all the rage, but a good white light filter is all you need to enjoy sunspots

and other phenomena like limb darkening. You only need the more specialist

filters for prominences and other coronal features.

I can see why folks use Questar for solar eclipses: enjoy the

partial with the filter in place, tracking meanwhile, then whip it off for

totality. The solar filter on the finder adds safety too.

The

sub-aperture Solar filter is standard, the full aperture worth buying for

photography.

Standard

model equipped with the full-aperture Solar filter.

To fit a

camera you need a 1.25” adapter which threads into the axial port.

In

Use – Astrophotography

To use the Questar for photography you unscrew the plug for

the axial port on the back of the control box and screw in a 1.25” adapter.

With the lever on the finder setting it’s then ready for imaging. Surprisingly,

the Questar fork mount is quite stable with a DSLR and photography is easy.

With its long focal length, the Questar is ideal for imaging

the Moon and Sun, both of which just fit on my DSLR chip, so both can be imaged

as whole disks. Note that poor seeing meant the Moon image isn’t as good as it

could have been.

The Questar with its accurate drive and long F.L. doubtless

also work well for webcam imaging of the planets, but I didn’t try this.

I did try some limited imaging of smaller deep sky objects

and the Questar yielded quite decent results on M57 and M13 with two minute

DSLR exposures at medium ISO, but the Questar isn’t a deep sky imaging scope.

Sun and Moon

through a modern Questar Duplex.

Choosing a Questar

Doing this review has changed and refined my views on which

Questar I’d buy if I ever get a modern one to complement my old Standard model.

My personal views are as follows.

I used to think I’d buy a fully-loaded quartz Duplex, on a

‘do it once, do it right’ basis. But having tested these Questars, I realise

that paying the extra for a perfect mirror isn’t going to turn a Questar into a

five inch APO, whilst on the other hand the basic optics are very good indeed.

The Duplex is a great idea, but I suspect that (like Ian, the

test Duplex’s owner) I’d be too afraid of damaging it to use it on a

photo-tripod out in the field. The same applies generally – I would want to use

the Questar for travel, but might be put off by a super-duper one, like the 50th

Anniversary, even if I could afford it.

So I would probably buy an ordinary Standard model, much like

the one on test here. But I would equip it with the Powerguide, a full aperture

Solar filter and probably (if I could afford it) a Tristand. Then I’d use it –

travel with it, take it to image and view things I couldn’t get at from home.

Rather than buying more Brandons, I’d specify it with an 8mm

and 12mm (you get to choose the two free ones, I believe), then go with TV

Plossls for low powers (32mm, 25mm and 20mm all work very well with the

Questar).

Summary

There is a perception that the Questar is bad value – plain

too expensive for what it is. Even the Wikipedia entry says so. But it’s just

not true. For what a basic Standard model costs, I’d argue that it’s quite good value if you consider that it comes

with a driven mount, finder with Solar capability, barlow, Solar filter, star

and Moon maps, two high-quality eyepieces and a fine case.

No, a Questar is not a big Dob’ or a fine small APO and

either may offer better views of certain objects in certain situations for a

similar outlay. But the Questar is a

convenient, portable, do-anything system in a way no other telescope I know is

(even a small APO).

To whinge about poor value compared to a Dob’ is ridiculous.

I know - I own both and have used both side-by-side and when I did so it’s

telling that I ended up putting the Dob’ away and using the hassle-free

Questar. The Dob’ is huge and lumbering, needs collimating every time I use it

and is anything but comfortable to use; finding things is difficult and when

you do, you need a stepladder. If seeing is poor, or the collimation still out,

the view through the Dob’ is a mush. The Questar is the opposite – it may not

show as much, but is always easy and convenient, always delivers a good view.

Size, brightness and limiting magnitude are not everything in this hobby.

There are a few niggles, but overall the Questar is a design

that has survived because it offers what few other systems (perhaps no other

system) does – a complete high-quality observing system in a carry-on case. Yes,

it’s a smart astro’ status-symbol, but a very useful tool as well.

I can’t deny that if you have a spare marble column in your

drawing room (left over from when the cat smashed the Rodin, perhaps) the

Questar will look good sitting on it. But

an Elitist image is no reason to disregard Questar.

Questar is highly recommended as a portable observing system

with maximum ease of use.

Note: A big

thanks to Ian Miller for parting with his two Questars over an extended period

for this review.

Everything you need to observe or image an eclipse or transit

fits in a small carry-on case.