Swift

Model 838 Review

Swift

Model 838 with ‘Saturn seen From Titan’ by Chesley Bonestell, from The Conquest of Space, 1958.

If

the past is another country, then the Sixties seem now like a strange mix of

France and Vanuatu – simultaneously close and familiar, distant and exotic.

I remember the Sixties - just. But it’s becoming increasingly

hard for me to imagine a time when TV was black-and-white, the

local car showroom had Morris Minors in the window and a calculator had cogs.

Then again, in the Sixties men went to the Moon, something beyond us today.

Back to the future.

Having

said that, though the Space Race was delivering feats we couldn’t match now, we

knew remarkably little about the Solar System in the early Sixties; really

astoundingly little. Even by mid-decade – my Swift Model 838 was made in 1964 –

planetary science had scarcely advanced from the days of Percival Lowell. So when some lucky girl or boy first unwrapped the Swift

Model 838’s deluxe wooden box, for birthday or Christmas, then breathlessly

assembled it and turned it on the Moon or a bright planet, they were looking at

terra incognita.

Again,

this is hard to imagine now. Children grow up with alien worlds delivered in HD

CGI with every SciFi blockbuster. But a

child looking through the Swift from the back-garden of a suburban semi in 1964

could look at real alien worlds and imagine … almost anything. Just a decade

later that would no longer be possible. It is this, I think, that imbues late

‘50s and early ‘60s telescopes like the Swift with a unique aura: one foot in

the fantasy-world of Lowell, the other in the space age.

Back

to 1964

To

set the Swift model 838 in context, I want to reach back to the mindscape of

its new owner in 1964.

Fifty five

years ago the Moon landings were years away, the first successful flyby of

Mars ditto. But to say that makes the early Sixties sound modern. In fact, in

1964 most of what we knew about the solar system came from a few professional

astronomers glued to the eyepieces of half a dozen or so large refractors, just

as it had for a century.

To

get a sense of what might have been in the Swift 838’s first owner’s mind, when

they first set their new telescope on the sky, I’ve assembled some quotes from

contemporary titles our new astronomer might have had on his or her bookshelf:

Mercury

“One

hemisphere is perpetually scorched by the solar rays, while no gleams of

sunlight ever penetrate to the far side.” (Guide to the Planets, Moore, 1957)

Venus

“when

we are confronted with two such dissimilar pictures, each supported by leading

astronomers, our lack of positive knowledge is brought home to us. On the

dustbowl theory, life of any kind … is obviously impossible; on the ocean

theory … there is a loophole for very primitive marine creatures.” (Guide to

the Planets, Moore, 1957)

The

Moon

“As the dividing line between light and

darkness, the terminator, advances, the floor of Plato grows darker. What

happens in the crater of Plato? Evaporation of moisture forming a light-absorbing

mist? Or just melting ice?” (The Conquest of Space, Ley and Bonestell, 1958)

Mars

“On the morning of June 4, 1956, I was

on Mount Wilson working with the 60-inch reflector … A magnification of 700

made it seem as if Mars were being viewed from a spaceship … The bright red

regions were covered with innumerable irregular blue lines, like veins running

through some mineral. Several minutes passed before it occurred to me these

markings must be canals.” (Mars, Richardson, 1965).

“… we are forced back to the most

obvious theory of all – that the dark areas of Mars are made up of something

that lives and grows.” (Guide to Mars, Moore, 1960)

Jupiter

“… these disturbances may be volcanic …

All this amid cliffs of permanent ice rising from a sea of temporarily liquid

ammonia!” (The Conquest of Space, Ley and Bonestell,

1958)

Seen in the context of such fanciful

ideas, a little scope like the Swift was, in 1964, a vehicle for fantasy and

exploration in a way no telescope can be today. But can we get a sense of this from using the

Swift fifty years on? Here I aim to find out.

At

A Glance

|

Telescope |

1964 Swift Model 838 |

|

Aperture |

50 mm |

|

Focal Length |

700 mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F 14 |

|

Length |

700 mm |

|

Weight |

~6 Kg including mount |

Data

from Me.

What’s

in the Box?

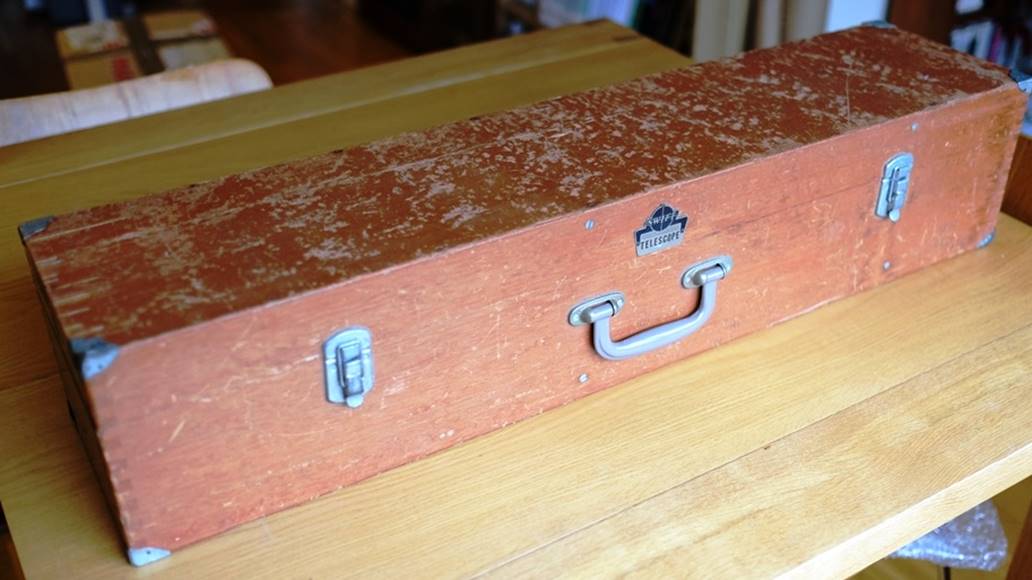

Like

many period refractors, the Swift comes in a very nicely made wooden box, lined

with green felt and with a place for every accessory.

Design

and Build

Many

have speculated on the fact that the Swift has styling and build cues that

remind of Takahashi. I will be discussing this attractive idea later, but here

I’ll just note that Swift weren’t alone. Check out a Sixties Carton or Prinz

and you will find much the same thing.

In

any event, the Swift is beautifully put together; but as we will see, those good looks also

translate to good performance (unlike a similarly elegant Unitron).

Optics

The

Swift Model 838 has a 50mm (2 inch) air-spaced Fraunhofer achromatic

objective of 700mm focal length ( F14 ). Given that

F15 is generally the focal ratio used for much larger achromats, we can expect

that the little Swift wouldn’t be troubled by false colour. I won’t pre-empt

the test, but in practice the view through the Model 838 is as free from

chromatic aberration as many ‘apochromats’.

The

lens is held in place in a simple cell with a lock ring; collimation is fixed.

The coatings are good quality single coatings and from what I can tell from the

reflections, all surfaces are coated. The elements are separated by simple foil

spacers like most small doublets. All in all, the Swift’s lens is superficially

no different from other small achromats of the day.

Tube

If

the optics look like any other, the Swift OTA is unique. External build quality

is very high: in a different class from say a Tasco of

the time. Instead of being held together by push-fit and screws, both the

objective cell and focuser attach by threads, as does the dew-shield.

Everything is made from metal and the castings are of high quality.

Whether

or not you like the trademark Swift finish, in two shades of coffee, it is

thick, smooth and has endured extremely well. The brochure proudly

boasts ‘enamel finishes are triple coated and oven baked’. Whilst the OTA is

gloss, the mount parts are crinkle-coated in a similar colour; so is the finder

mount, which looks odd on the gloss tube, but is original. That crinkle coating

is very period – I recall my father’s late Fifties typewriter was covered in

it.

Focuser

The

focuser is perhaps where the Swift departs most obviously from the run of the mill

‘60s Japanese refractor – it is beautifully designed and engineered. Everything

about it, from the thick draw-tube chrome, to the accurately machined, wide

cross-cut rack is of the highest quality pre-CNC could deliver. It is much

closer to a Tele Vue or Takahashi focuser than to a Tasco.

The

focuser looks good, but it is also smooth, accurate and free from play or image

shift. Shine a torch in the end and you can see that it’s baffled and

flat-black painted too. The visual back is a twist ring like a Takahashi with

no set screws and it too works very well; it is even inscribed with which

direction to turn to tighten or loosen it. It’s a design that Baader have re-discovered with their ‘click-lock’

accessories. If Swift were doing this in 1964, why do we still

suffer the set-screw?

The

draw-tube has a remarkably long travel. Why? Japanese observers like to use

their refractors straight through and the Swift allows this without an

extension tube.

On

top of the focuser is a proudly embossed name plate with a serial number, again

reminiscent of a Takahashi

The

only down-side to the focuser is that it takes only 0.965 accessories.

Name

plate, serial number and cast wheels – like a Takahashi?

Swift

focuser at full travel – an extension is never needed.

The

Swift mount, with its trademark teardrop weight, is also unique to the brand.

It’s finished in the same dark-coffee crinkle as the finder ring.

Mount

The

mount is a German equatorial, but has no motor or even slow-motion controls; arguably

it doesn’t need them. The push-pull action of the axes is perfectly weighted

and super-smooth with no backlash. Classysilver-on-black

(Takahashi-like again?) setting circles are provided.

The

basic action of the mount is excellent – if only most modern alt-az mounts were this smooth. But it’s not flawless. One

problem is the setup’s weight: so light that it’s easy to move the tripod when

you push the mount axes around and the slightest nudge of a toe in the dark

budges it enough to lose your position in the sky.

That

light weight makes the Model 838 perfect for grab-n-go, from a time before the

idea existed.

A

slightly more serious problem is vibration. The OTA is light but long and

focusing causes a lot of vibration that makes finding critical focus hard at

higher powers. Again, a slight knock whilst viewing causes significant vibes.

Interestingly,

Swift use exactly the same mount for the next model up in size – the 60mm Model

839 – and a friend who owned one tells me it is ‘very wobbly’ with the bigger

OTA.

Accessories

The

Swift comes in a quality wooden box with a range of accessories. Unusually, the

accessories for the Swift are really good, so I’ll discuss them in detail. All

are 0.965” fit and all feature the same twist-lock mechanism as the visual

back.

The

20mm Huygenian eyepiece is optically quite

decent, but it has little eye relief and a steeply conical top. In the dark,

it’s all too easy to poke yourself in the eye with it – ouch!

The

9mm ‘Sym’ is effectively an Orthoscopic and it’s really

quite good quality, given the same poke factor as the 20mm (my eye still hurts

from last nights’ viewing). However, give the Swift a modern eyepiece, like my

7mm Tak’ ortho’, and it moves to another

level.

The

finder is particularly good for an old scope and much better than most cheaper optical finders today. It’s labelled 5x24 and

though the field is narrow compared to say a Takahashi 5x25, the view is bright

and sharp. The objective is a coated achromat, mounted in a little cell,

whilst the eyepiece has good eye relief. Internally, it’s been properly

flat-black painted, so stray light is no problem and it hasn’t been stopped

down unlike many finders of the era.

A

good quality 0.965” prism diagonal with a twist grip eyepiece holder comes with

the Swift and like the eyepieces is in the same coffee livery as the OTA.

Doubtless a modern multi-coated version would improve brightness a bit, but

decent 0.965” diagonals are virtually unobtainable now; you’d need a

0.965”/1.25” adapter to use a larger diagonal.

Like

many Japanese telescopes of the day, the Swift comes with an erecting prism.

Unlike almost any other example I’ve seen, this one is a top

quality item that introduces no aberrations at moderate powers and turns

the Swift into a sharp daytime spotter. To use it, you unscrew the visual back

and thread in the prism unit, making it an integral part of the scope and a big

improvement over push-fit.

Finally,

the Swift includes a barlow lens. Once

again, it’s a different from the usual. Most barlow lenses

I’ve seen included with older Japanese scopes are rubbish, so much so that bad

experiences of Tasco’s barlows in

the Seventies gave me a long-held prejudice against the things. Swift’s is an

excellent device, though: metal bodied, clamp ringed (like all the accessories)

and optically so good that introduces no significant aberrations and works

really well.

Swift

5x24 finder is scarred on this example, but is still bright and sharp.

Like

all the other accessories, the Swift barlow is

a good one.

Yes,

but is it a Takahashi?

Do

we have to do this now? Oh alright then … There is a

theory going the rounds that Swifts are basically early Takahashis. But having owned or reviewed numerous Takahashis, I can categorically state that … I’m not sure.

The

Swift undoubtedly has features in common with a typical Takahashi, including

the look of the castings, the twist-lock visual back and diagonal, the

clamshell and the design of the focuser. Certainly, the overall quality is

Takahashi-like. But whether these are just features that premium Japanese

makers shared in common at one time, or whether they are evidence of a manufacturing

or design link, I can’t say.

In

Use – Daytime

My

usual test of viewing tree branches against a bright sky at 100x magnification

gives a dim but sharp view. False colour is present at about the level of a

fast doublet APO (think TV-76), so is mainly seen out of focus and isn’t

intrusive.

In

Use – The Night Sky

General

Observing Notes

The

Swift cools very quickly and is a pleasure to use: the focuser is quite smooth,

accurate and free from image shift. Best focus is a very definite point, a snap

if you will, like all good optics.

For

fun, I’ll quote the original Swift manual to see if the description for each

Solar System target is accurate. Sometimes these quotes seem cryptic, strange

or nonsensical – don’t blame me! The same Manual recommends making a ‘hat

trick’ shutter for photography from ‘ordinary shit cardboard’!

The

Moon

The

Manual Says: ‘Approx. 5000 craters. Dia of

minimum spot: 4.5 miles. Width of minimum crevice: 550 yds.’

A

Day 27 crescent in pre-dawn twilight with the standard H20 eyepiece gave

good contrast and a very sharp image at 35x in stable seeing.

The

little Swift holds up well at 100x with a modern 7mm Tak Orthoscopic,

giving a slightly dim view that is completely crisp with surprising detail. As

an example of the limits of its resolution, Rima Huygens is visible at first

quarter, but the Hippalus rilles, at the boundary of Mare Humorum,

are not.

Mercury

The

Manual Says: ‘Disc image can be seen.’

Mercury

is well-defined and obviously not a star, but the disc is still minute at 100x;

Mercury’s phase is barely discernible.

Venus

The

Manual Says: ‘Eclipse can be seen. Ordinarily appears as a crescent shape.’

Venus

shows a well-defined gibbous disk and no native chromatic aberration (though

lots from the atmosphere). Venus looked good, even low in poor seeing – perhaps

due to the combination of small aperture and long focal length.

Mars

The

Manual Says: ‘Polar cap and Lake Sirutis visible

when near Earth.’ (!!)

Mars

is visible as a tiny orange disk, but I have yet to see any detail through the

Model 838, except perhaps the hint of a polar cap. I am still holding out for

those promised views of Lake Sirutis though.

Jupiter

The

Manual Says: ‘looks elliptical, 2 bands can be seen’

The

little Swift excels on Jupiter, giving a very

crisp view with no chromatic aberration at 100x with 7mm Tak ortho’. Four belts, the polar hood and some detail

in the Southern Equatorial Belt (dark spots) can be made out at that

magnification. Contrast delivery seems excellent for the aperture.

Jupiter’s

Galilean moons are clearly disks and I was able to

watch a shadow transit with the Swift.

Saturn

The

Manual Says: ’The ring can be seen. Satellites Titan and Rhea are also

visible.’

At

the time of the test, Saturn was still very small, but 100x again delivered a

surprisingly good view for such a small telescope. The rings were clearly

discernible as such (i.e. not as Galilean ‘handles’!), along with the ring

shadow. I couldn’t make out the Cassini division, though.

Deep

Sky

M42

The

Orion Nebula looked quite good through the standard H20mm eyepiece, but a bit

dim due to single coatings (on the eyepiece and prism diagonal, as well as the

objective).

M13

A

surprisingly good view was to be had of this bright globular cluster, but there

was only the vaguest sense of resolved stars with averted vision.

Doubles

Castor

easily split into two hard ‘balls’ with black space between. Epsilon Lyrae –

right on the Swift’s theoretical resolution limit - was resolved into

‘dumbbells’, but was not cleanly split.

I

was unable to split Rigel (B was lost in the diffraction rings).

M57

The

Ring Nebula was easy to pick out and showed

as a smoke ring with averted vision, but like M42 was a bit dim.

Summary

The

Swift Model 838 is a beautifully made instrument and is highly usable today,

unlike many classic scopes that have poor optics. The only wonder is that Swift

lavished so much care on a 50mm scope. Having said that, the little Model 838

is light and portable in a way that the bigger Swifts of that era aren’t. The

mount is passable for the 50mm OTA: smooth and accurate, but a bit vibey.

A

mere two inches aperture it may be, but the Swift’s optics are essentially

perfect and virtually free of chromatic aberration, so it shows you more than

you would expect, especially when it comes to the Moon and planets. I

think I can imagine the thrill the Model 838 must have given its original

owner, peering at Mars and glimpsing the polar cap, whilst reading Moore’s

original Guide to the Planets by a big chrome ‘60’s flashlight.

Unitron may

be the more famous brand, but optically the Swift is far better than the

60mm Unitron I once owned. It’s both a travesty and an opportunity

that classic Unitrons are so much more

expensive than Swifts today.

Incidentally,

the Swift’s optical quality is also better than my 1964 Questar.

It’s

no coincidence that unlike many classic scopes, this

particular Swift has been both well cared for and well used.

Something about the Swift makes it easy to imagine oneself back to 1964 when

using it: an indefinable Sixties character that I really like.

Given

some of the dreadful telescopes made since, it’s chastening to realise how well

a small refractor could be made fifty years ago, back when even some

professional astronomers still believed in Martians.

It

is only a 50mm scope after all, but as a usable and affordable classic, with

top quality optics and mechanicals, the Swift Model 838 is highly recommended.