Takahashi

Mewlon 180C Review

Takahashi’s Mewlon

range has been around for many years. The larger sizes – 250mm and 300mm

(10” and 12”) are now frighteningly expensive, but this 180mm, the

smallest of the range (there is an in-between 210mm as well), is a bit of a

Takahashi bargain, especially when you consider it includes all the mounting

hardware and a nice finder that would cost extra on a typical Tak’

refractor. What’s more, they’ve recently revamped it, so I thought

it was high time I tried one and reported back.

So what then is a Mewlon

and why might you want one?

The management overview is that the Mewlon is an affordable planetary reflector - lighter,

quicker cooling and possibly sharper than the SCTs and Maks you get from

Celestron, Meade and Skywatcher. I’ll cover the details in the

‘optics’ section below.

At

A Glance

|

Telescope |

Dall Kirkham Cassegrain |

|

Aperture |

180mm |

|

Focal Length |

2160mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F12 |

|

Central Obstruction (incl. holder/baffles) |

33% |

|

Length |

625mm |

|

Weight |

6.2 Kg |

Data from Takahashi.

What’s

in the Box?

The Mewlon came in one of Takahashi’s nested boxes:

I do like a

good Takahashi unboxing!

Design

and Build

The Mewlon

series used to be a family of four optically near-identical planetary

reflectors, but nowadays Tak’ have turned the two larger models (u-250

and u-300) into imaging scopes with sub-aperture correctors. However, the two

smaller models, including this one, remain pure reflectors aimed at high-power

visual use and those looking to image smaller objects.

Similar Takahashi quality –

complete with the beautiful castings Tak’s specialise in - can be

expected throughout the Mewlon range, but the u-250

does get some extra refinements in line with its high price, such as an

electric focuser and removable back with special vented cell for fast cooling.

The u-250 and u-300 are very large and

heavy scopes, whereas this 180 is quite small and very portable.

Mewlons

compared. L to R: u-180C, u-210, u-250.

Optics

Takahashi’s Mewlons

use an optical design known as a Dall-Kirkham. A quick diversion into optical

theory to explain this is in order first. As usual, if you know this stuff,

just skip it.

Most telescopes with mirrors fall into three

basic camps:

1) Newtonians. Mostly found mounted as Dobsonians, they have just (two) mirrors. Newtonians are

cheap, sharp, quick cooling and generally excellent. However, they have a lot

of off-axis coma that needs correcting for imaging and the tube is very long

for anything over F6.

2) Catadioptrics. These have a

combination of mirrors and a glass corrector plate. Common as Schmidt and

Maksutov Cassegrains from the likes of Meade and Celestron. They are much more

compact and can have better off-axis correction, but are heavy and slow to cool

because they entrain the air in the tube and have a large glass mass.

3) Cassegrains. These are mirror-only

telescopes, but have a folded light path to give a short tube and prime focus

at the back. Professional telescopes are usually some variant on the Cassegrain.

Early examples are Classical Cassegrains, which have a parabolic primary mirror

like a Newtonian, but a hyperbolic secondary, for example the 60” Hale

(reviewed here) and

100” Hooker (here)

telescopes at Mt Wilson. Classical Cassegrains are sharp centre field and have

good off-axis correction, but are typically of slow focal ratio (~F15).

More recently, the pro’s

have moved on to designs allowing shorter focal ratios, like the

Ritchey-Chretien. Meanwhile, the Classical Cassegrain’s hyperbolic

secondary is a difficult curve to grind into a mirror, so there have been few made

for amateurs (Tak’ made one of the few). Which is where the Mewlon comes in (at last I hear you cry!)

The Mewlon is

a type of Cassegrain called a Dall-Kirkham. Like the Classical, it has only

mirrors, but the complex parabola/hyperbola is replaced with a simpler (i.e.

cheaper) ellipse/sphere. This gives the DK Mewlon

excellent performance on axis (i.e. for small DSOs and planets), but worse

off-axis aberrations than the Classical for wide field imaging.

So, what

advantage does the Mewlon have over the usual SCTs

and Maks? No corrector plate means less weight, fewer optical surfaces to get

out of alignment and less light scatter. Cool-down should be faster too because

the Mewlon has an open-tube like a Dob’.

The DK has a

longer (F3) primary mirror than a typical SCT. This should make collimation

easier, but it means a longer tube for the aperture.

Finally,

how is this new version of the Mewlon 180 different?

Optically, the big difference is in the mirror coatings, which now have

multi-layers on both surfaces for a 7% system improvement in light throughput.

Takahashi refer to these as, ‘HR Multi-Coated’.

I should

also point out here that Takahashi finish the mirror polishing in-house and

each pair is a matching set. Bench tests suggest Mewlons

have excellent optics and this one certainly does, as we will see.

The 60mm

(30%) central obstruction is increased slightly to 33% by the baffles, but

that’s still less than most mass-produced SCTs, which typically have 35-37%.

This is important for contrast and for the Mewlon’s

planetary and lunar potential, also for performance in poor seeing.

Baffle tube contains some 10 knife-edge baffles. Secondary is 60mm –

just 30% by width, less than most SCTs and Mak’s.

Tube

The tube rolled

steel, but the join is welded not folded and has been carefully finished

externally to hide the seam. The front of the tube is elegantly rolled over.

Everything is perfectly blacked inside. Finish is pale cream enamel with the

newer blue-green powder coat on the cast parts (more on Takahashi’s

changing colour schemes here).

Despite the

longer-than-SCT F3 primary, the tube on the u-180C is reasonably short,

possibly short enough to be carry-on portable with the visual back (and maybe focuser

knob too) removed.

The rear is a

superb one-piece Takahashi casting. Whereas on the u-250 this can be removed

for cooling to reveal a vented cell, on this u-180 it is fixed.

The Mewlon 180 has a thin, three-vane spider, for better contrast

than thick vanes. The secondary holder is fronted by a logoed blanking plate -

nicely machined out of metal and threaded on.

Takahashi make

a marketing point of the carefully constructed baffle tube containing 10

separate blackened ridge-baffles for contrast and stray light protection. The

secondary is also shrouded by a deep baffle. I’ve seen under-baffled

Cassegrains that are horribly sensitive to stray light, so this is a vital part

of the Mewlon’s notable contrast.

All Mewlons have their finders cleverly mounted into a cast

handle that attaches solidly to the cast back-plate. This makes the OTA easier

to mount, but also makes for a super-stable finder mount that never loses

alignment.

The tube is

covered by a unique vinyl cover with a Velcro tightening strap.

Focuser, 2”

visual back and typical Tak’ 1.25” adapter.

Detail of unique

(to Mewlons) 6x30 finder-handle.

Focuser

Like almost

all Cassegrains, this Mewlon 180-C focuses by moving

the main mirror by a substantial knob that protrudes from the visual back

(which stays fixed). This gives the Mewlon an

enormous range of focus – enough to accommodate straight-through viewing,

a 2” diagonal or a DSLR without extension tubes. The mechanism is smooth

and accurate too.

The downside

of moving-mirror focus is some image shift when changing focus direction. The

larger Mewlons avoid this with a different focus

mechanism which moves only the secondary via an electric motor and handset.

This

version of the u-180 has a 2” visual back; the old was limited to

1.25”. This makes a

substantial difference. In fact, I’d argue that 2” eyepieces are

much more necessary here than in a small refractor. Why? Because otherwise a

focal length over 2m means a maximum field of view of just 0.72°, seriously limiting the scope for deep sky.

But now,

with the largest 2” eyepiece, a 55mm Plossl,

the Mewlon has a maximum FOV of 1.2° - just enough to fit in the whole Pleiades open

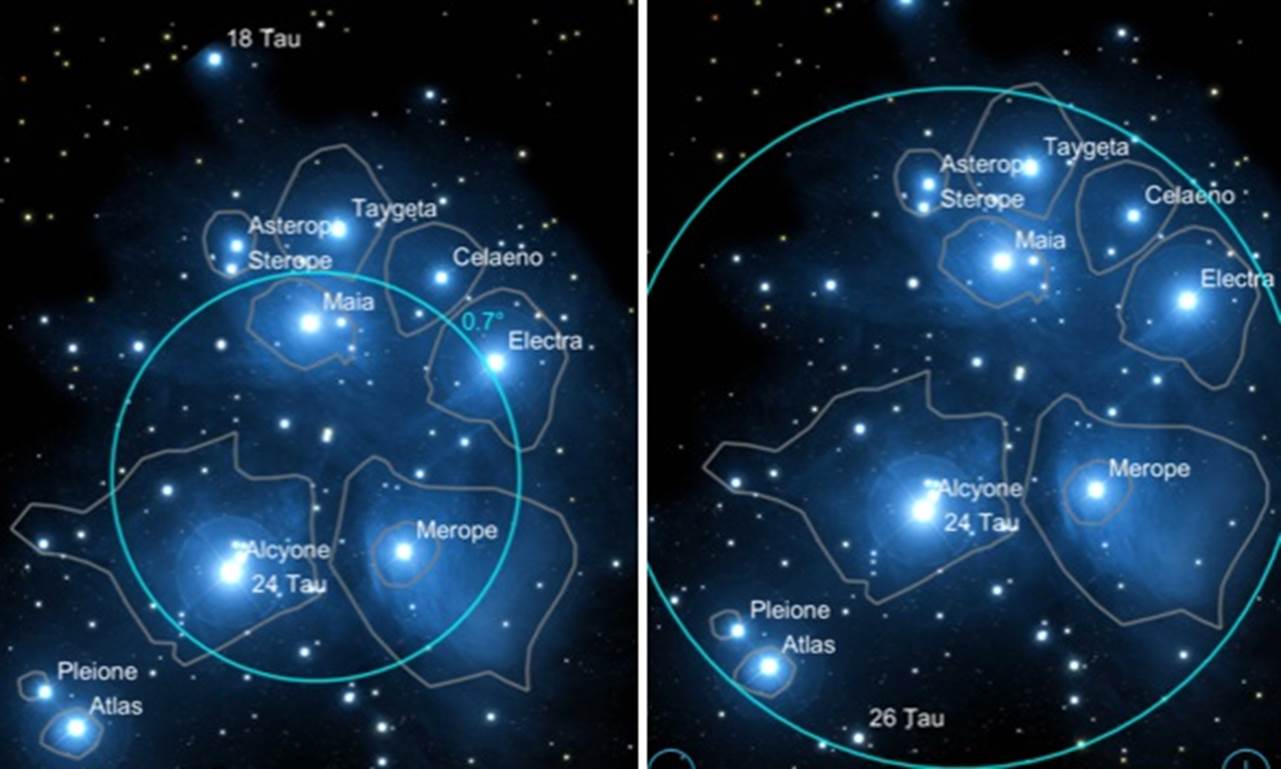

cluster. In case the improvement from 0.72° to 1.2° doesn’t sound like much, check out the

difference on the sky in the simulated image below:

Mewlon 180C maximum

FOV with 1.25” and 2” eyepieces compared on the Pleiades cluster.

Mounting

The u-180C

is reasonably light weight at just over 6Kg, mainly thanks to no corrector

plate. However, that still makes it push the ~7Kg weight limit for the smallest

equatorials and the 180C would work best on a mid-size mount like an HEQ5 or

similar (or, of course, Takahashi’s own EM-11 or EM-200).

The Mewlon range all have a dovetail plate attached to a

casting underneath the tube. This avoids the need for tube rings. The dovetail plate is intended for

Tak’s own mounts, but has the same chamfer-angle as the Vixen-compatible

ones found on most small mounts. I have seen

a heavy-duty after-market Losmandy D dovetail

attached to a u-250, but that shouldn’t be necessary for the u-180C.

The Mewlon ships with a quick-release dovetail clamp for their

own mounts.

Dovetail is

Tak’s own, but generally Vixen compatible.

Vixen SX2

handles the Mewlon 180C’s 6 Kg weight

comfortably.

Mewlon 180C and

refractor of similar aperture (TMB 175).

Accessories

Takahashi

make a version of their fine rack-and-pinion focuser that attaches in place of

the standard visual back. This gets around the image shift, but would only be strictly

necessary for ‘serious’ imaging.

Also for

imaging, Takahashi make a 0.8x reducer for the Mewlon

that flattens the field and shortens the focal ratio from F12 to F9.6 (1730mm).

By Tak’ reducer standards, the Mewlon reducer

is good value too.

In

Use – Astrophotography

One big

advantage of the focuser is huge travel and you can stick a DSLR straight in

the back, with no need for wobbly extensions.

The 2”

VB on this new version is not a trivial upgrade: on this new version, a

full-frame DSLR can image the whole Moon for example (on APSC it won’t

fit) and larger DSOs.

The image of

the Moon isn’t bad, if not as good as a fine apochromat. The problem

seems to be that things get progressively less sharp toward the field edge (the

Moon takes up most of the field vertically), in line with the

Dall-Kirkham’s promised off-axis coma.

The sub of

the Crab Nebula (M1) with an APS-C sensor shows classic off-axis coma. With a

full-frame DSLR, this sub of the Eskimo Nebula shows just a bit more. Only the

brightest stars show spider-vane spikes.

M1: Fuji

X-Trans APS-C, 110s ISO 6400.

Eskimo

Nebula: Canon EOS 6D MkII Full Frame, 120s ISO 3200.

Moon: Canon

EOS 6D MkII Full Frame. Slightly increased contrast.

In

Use – The Night Sky

Collimation

My first

looks at the Moon with the Mewlon were disappointing

– slightly soft and without the clarity and snap I was expecting. Then I

reminded myself, ‘this is a reflector, those things that need

collimating’. Ah yes ... collimation, my favourite job.

The manual

says that collimation is set at the factory and should survive shipping; well,

not in this case. A quick star test showed it was off.

To collimate

the Mewlon, you unscrew the blanking plate on the

secondary housing to reveal three Allen bolts (much better than the screws on

an SCT). I attached the Allen wrench (supplied by Tak’) to a piece of

cord and looped it around my wrist – much too easy to fumble and drop it

on the primary mirror otherwise (no SCT or Mak’ plate in the way).

A few tweaks

on the bolts - tightening the one(s) on the side where the diffraction rings

are compressed and slightly loosening the opposite to compensate – got a

nice round diffraction pattern and tightened the in-focus diffraction pattern

too.

After

collimation, the Moon snapped into focus and was sharp and full of detail and

contrast. Ready to start observing (and not as painful as past collimation

experiences)!

Removing the

secondary cover reveals collimating hex-bolts: don’t drop it!

General

Observing Notes

No corrector

plate and well-recessed mirrors mean the Mewlon is

resistant to dewing. One dewy morning, the refractor alongside was hazing up

whilst the u-180c remained clear.

One

surprisingly fantastic thing about the Mewlon

(really!) is the finder. Tak’ finders are always good, but this one is

just superb – very sharp with a wide field and loads of eye relief. But

the best thing is that holder. It’s super strong and stable because

it’s also a handle. But that means you set alignment once and it’s

always perfect.

Being able to

rely on the finder putting things bang in the centre of a high-mag eyepiece is

a great feature and makes getting around a doddle with the Mewlon

(so much easier than a small refractor I was using alongside with a dodgy RDF).

Like all

reflectors with larger obstructions, the Mewlon does

suffer in bad seeing compared to a small refractor – a theme that keeps

cropping up on this website for those in northerly climes with a crummy thick

and wet atmosphere above them.

The focuser

is smooth with masses of travel, but does have some image shift when changing

direction (and this is a brand new scope, so wear is no excuse here).

Cool

Down

When I’m testing small refractors,

this section is just this one line. Not now.

If you are used to refractors, the Mewlon’s terrible view and boiling tube currents

during cool-down are off putting. You wait and wait. After 45 minutes from a

warm room, there’s still terrible spherical aberration and a huge plume

in the star test, but at least at lower powers the view is good now. Wait some

more.

After almost an hour, the Mewlon will finally just split Rigel, but spherical

aberration and plumes are still writ large in the star test. Maybe the Mewlon does cool faster than an SCT or Maksutov, but it’s

much slower than, say, a 4” doublet refractor like an FC-100D.

An hour and twenty in and we’re

still not there. I get the FC-60 out for a quick look while I’m waiting;

it gives a good view in minutes. This is the ground truth of astronomy in cold

climes.

After an hour and a half, the Mewlon’s spherical aberration has almost gone at last

and the star test finally looks normal.

This Mewlon

250 has a vented cell and removable cover to aid cooling. The smaller models lack

this feature.

Star

Test

The star test

shows spherical aberration during cool-down, but thereafter it’s just

perfect – identical, sharply-defined and evenly illuminated diffraction

rings either side of focus. It’s a Takahashi after all, even if,

unusually for me, one with mirrors.

The

Moon

The Mewlon has a better field of view than I was expecting. The

whole Moon fits into the field of a 32mm Plossl at

68x, but it’s painfully bright after a run of small refractors and you

need a filter or much higher powers to kill that brilliance.

A gibbous

Moon showed lots of crisp detail, even in seeing that was moderate at best. I

was able to spot three craterlets in Plato and a rille or two in Gassendi

without difficulty. The Moon has a wonderful whiteness if you’re used to

refractors or SCTs – zero false colour with its all-mirror system.

Using the Mewlon on top of my 7” LZOS refractor and comparing

their view of a 3-day Moon, I notice that the Mewlon

suffers a bit worse in the poor seeing and scatters a bit more light from the

limb, but that it also delivers a noticeably whiter tone to the brilliant Lunar

highlands.

On a

different night of decent seeing, I used a 15mm Panoptic giving 144x to explore

the extended and difficult Sirsalis rille and look

for more rilles and craterlets in Gassendi. At its best like this, the Mewlon gives a 5” apochromat level of lunar detail.

At 240x with a 9mm Nagler, it’s a still great view – very detailed

and involving and sharp (once it’s cooled).

In good

seeing, the Mewlon will reveal most of the features

in this Moon atlas.

Planets

Once cooled and on nights of better seeing, I had some excellent views

of both Jupiter and an opposition-year Mars (albeit low in the sky).

I found that simple eyepieces worked best for planets with the Mewlon and my favourite views were with Zeiss Abbe Orthos, particularly the 10mm giving 216x.

Mars

The huge focus travel meant I could view a low Mars with the eyepiece

straight in the visual back (no diagonal). Mars then showed some significant

albedo detail like Syrtis Major and Mare Acidalium,

possibly some limb cloud too. The view was similar to an apochromat in the 110-130mm

range, albeit with more unfocussed light from mirror scatter and spider

diffraction.

Jupiter

In good seeing, I had fine views of Jupiter too – multiple cloud

belts and dark embedded storms.

Uranus

“Can you see Uranus with that scope, mister?” Yes!

Uranus showed up as its usual dim bluish disk – noticeably a bit

more in need of averted vision than through a similar-aperture refractor (my

TMB 175).

Deep

Sky

With a 32mm Plossl giving 68x and the maximum 0.72° field of view for a 1.25” eyepiece, the Orion

Nebula (M42) fits nicely in the field. Even with a full Moon in the Hyades

nearby, I see knots in the nebulosity around the Trapezium stars and in the

extended arms, even a hint of colour: much more nebular structure than you get

with a small refractor. Those ten baffles certainly deliver good contrast and

protection from stray light is excellent.

The 180C is

particularly suited to smaller DSOs and I had some exceptional views of the

Crab, the Ring and the Eskimo. That superb contrast is really noticeable here.

Trying to

view a larger DSO, like the Pleiades open cluster, you realise the limitations

of a 2m focal length: just a couple of the Seven Sisters fit in that maximum 0.72° FOV of a 32mm Plossl. Then

I remember this isn’t an old Mewlon, this one

will take a 2” diagonal! With a 55mm Plossl

there’s doubtless some vignetting, but all Seven Sisters now just squeeze

into the field of view, sparkling nicely amid silvery nebulosity that is much

more noticeable than through a small scope.

Despite the

DK’s reputation for off-axis aberrations, stars remain points until

70-80% field width and even after that just become mildly comatic. I believe

Tak may use an outsized mirror to help. Stars retain lovely true colours too

(zero false colour remember).

The Mewlon splits doubles well and Rigel’s companion

showed up at 144x with a 15mm Panoptic, as clear and bright as I’ve ever seen

it, even with the full Moon close by.

Summary

The Mewlon is mostly good and its negative points are simply

those suffered by all reflectors.

Optical and

mechanical quality are outstanding as you would expect from Takahashi (this one

has a virtually perfect star test). The mirror-only optics deliver bright views

and are much more resistant to dewing up than an SCT or Mak’.

For its size

and weight, it offers excellent lunar and planetary views – at the level of

a bigger and more expensive apochromat. The field isn’t nearly as bad

off-axis as I was expecting either and with the 2” visual back you can

enjoy lower powers and bigger DSOs, or the whole Moon.

Even for

imaging, the field is surprisingly good for smaller sensors. The Mewlon would make a great tool for imaging smaller DSOs. Note

that you only get obvious spider spikes on the brightest stars.

Compared with

a Takahashi refractor of similar capability, the u-180C is something of a

bargain too.

As with all

Cassegrains, the Mewlon has three less positive

aspects if you are used to small refractors:

1) In terms of size it could be a quick-look scope, but

the lengthy (hour plus on cold nights) cool-down counts against this in cold

climates

2) In poor seeing it suffers compared with smaller

refractors

3) Like all reflectors, the Mewlon

may need periodic collimation, especially if you travel with it. But

collimation isn’t hard to do on a star at high power

One final

niggle is the focuser. It’s buttery smooth and has masses of travel,

which is very convenient (no extensions required for DSLR imaging). But there

is some image shift, like most moving mirror focusers.

The Mewlon

180C makes an excellent and surprisingly multi-purpose alternative to a

mid-sized apochromat: for the Moon and planets, but for smaller DSOs too. The

brighter optics and 2” visual back make it much better for extended

objects than the old version. Highly recommended.