Buyers’ Guide to Two-Inch

Refractors

If

you want a really, really small astronomical telescope this is the size

you’ll pick from. Why might you want such a thing?

The

obvious answer is for super wide field imaging, of Barnard’s Loop for

example. Yes, a camera lens will do the same job at 200-300mm focal length, but

most distort stars too much in the periphery.

For

visual use, the answer isn’t so much about the scope as the mount.

The

smallest scopes in this class will go on a small photo tripod/pan head that

might weigh just a kilo or two in total. If you’re viewing from an urban

park and the local yoof [sic] turn up and seem in a

mean mood, you can pick it up in one hand, tuck it under your coat and just

walk off. If you’re off on holiday, you can pack it in your luggage

without much planning or moaning from your significant other.

Please

note that I have tried many, but not all, of the scopes listed here so some

descriptions are hearsay – if you know better, get in touch!

I’ve

extended this Guide to (arbitrarily) cover refractors from 25mm to 65mm and

some achromats. There are, of course, numerous 50mm and 60mm beginners’

scopes out there; I may include a few eventually.

I

will add more scopes to this guide in due course.

Table

of Contents

Borg Mini Series

Before I start describing the exhaustive (and exhausting) range of Borg objectives in the 2” size range, a brief discussion of the Mini Borg system in general. I’ll try to keep the cube and assimilation jokes to a minimum.

Borg are a Japanese brand, part of Tomy, a toy company. Perhaps that’s why Borg’s is like no other telescope range: it’s a really a constructor set to build scopes and camera lenses. Remember those kids’ sets for building things, Meccano and Lego? That’s Borg, but for scopes.

But don’t think that means Borg are low quality. In fact they’re some of the most refined small scopes. Recent Borgs feature Canon/Optron lenses incorporating fluorite and of the highest quality (and, ouch, price).

Perhaps the most important feature of Borg scopes is small size and ultra-light weight. For example, a Mini 60ED rig will be about half the weight of the next smallest apochromat with similar specs, the TV-60. That differential is true across the range.

Borg seem to work by ordering a limited run of a particular lens and then moving on to a new model, so there are a lot of subtly different objective designs out there, as you can see below. For all these Borg entries you’ll notice I focus on the objectives, which are interchangeable and can be bought separately. But what about the tube?

Trouble is there are many possibilities. The original Mini 50 was widely sole in the 54mm drawtube OTA you see in the photo below, but even that can be equipped with various focusers and visual backs. It’s a super-light rig because there is ¼-20 thread built in.

More recent Mini Borg tubes are black and have a built-in Arca dovetail; others have mini tube rings. All the Borg objectives up to and including the 72FL can be fitted with an adapter to go on the Mini Borg tube. However, you can as easily go the other way – all the smaller lenses can be adapted (that word gets used a lot with Borg) to the Series-80 (80mm) tube system.

Note that the objective lenses listed below vary from 250mm to 500mm focal length, so even though they all physically attach to the Mini Borg tube assembly, some won’t come to focus. This isn’t the problem it might be, because Borg will sell you various thread-in extensions to increase the tube length.

Usefully, the Mini Borg OTA can be equipped with a 2” visual back and Borg sell various thread-on wide camera adapters (or a T-ring adapter).

Borg Pocket 25

|

Lens Design |

Doublet

achromat |

|

Aperture |

25mm |

|

Focal Length |

175mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F7 |

|

Length |

~120mm |

|

Tube diameter |

30mm |

|

Weight |

~175g OTA |

The smallest scope I’ve ever encountered, the Pocket Borg is a 25mm achromat in its own tiny drawtube OTA. It looks super-cute, but I honestly didn’t find it useful except for (very) quick looks at the Moon.

Borg 36ED

Stock Image.

|

Lens Design |

ED doublet |

|

Aperture |

36mm |

|

Focal Length |

200mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F5.6 |

|

Length |

N/A (varies) |

|

Tube diameter |

48mm |

|

Weight |

70g objective

only |

The 36ED has always struck me as a puzzle. Though I’ve never tried one, I’d have to ask what it’s for. Yes it’s the world’s smallest ED astronomy lens. But given the Mini 50 is quite well corrected as an F5 achromat, what extra does a 36mm F5.6 ED apochromat give?

The answer may be imaging: this will give very clean star images free of violet bloat and a huge field of view from a focal length of just 200mm.

The 36ED is still available, in Japan at least, but it’s far from cheap at around Y37,000 list price for the objective.

Borg Mini 50 Achromat

Mini 50 with

a TV-60.

|

Lens Design |

Doublet

achromat |

|

Aperture |

50mm |

|

Focal Length |

250mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F5 |

|

Length |

168mm as shown |

|

Tube diameter |

54mm |

|

Weight |

~550g OTA as

shown |

The Mini 50 was what got Borg started on the whole 2” astro-scope thing. As you’ll see below, it’s since been quite a mini-scope odyssey.

The Mini 50 is just a basic achromatic doublet, but at 50mm that matters much less than you might think, even at F5. False colour just isn’t the problem you expect and the Mini 50 will comfortably take higher powers on the Moon and planets without breaking out into fairy-light purples and greens. I’ve even had very decent views of Mars with hints of albedo markings. The reason for this goodness seems to be that it’s fabricated to astronomy standards, i.e. it isn’t just a re-purposed binocular objective.

The main thing about the Mini 50 is that it’s really small and even lighter – under 500g ready to mount and use, less than a third the weight of the TV-60!

It may be the cheapest and the original, but the Mini 50 is perhaps my favourite of all the small Borg objectives – all you really need, for visual anyhow, at this size.

Borg 45 ED/EDII

|

Lens Design |

ED doublet |

|

Aperture |

45mm |

|

Focal Length |

325mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F7.2 |

|

Length |

N/A (varies) |

|

Tube diameter |

54mm |

|

Weight |

100g objective

only |

The

45 ED was intended to be the upgrade path for owners of the Mini 50 OTA who

wanted better correction for high powered views or perhaps for imaging (In

Japan, Borgs are widely used for nature photography too).

To

this end, the 45 ED has specs that should allow it to perform to the maximum

allowed by its aperture – significantly slower than the Mini 50 at F7.2

and with ED glass as the positive element in the doublet.

Trouble

is, my original 45ED, dating from about 2008, just didn’t live up to the

expectations at all. It was an expensive lens, but for most things the Mini 50

outperformed it. True, it had almost no visible false colour, but it just

wouldn’t take high magnification, going all grainy and washed out by

about 80x.

I’ve

since wondered if those original lenses did indeed use an ED element intended

for a low-fidelity application – a camera or binocular lens perhaps

– with insufficient final polishing. Make no mistake, such lenses meant

for small image scales are not good enough for astronomy. We will never know,

but a clue may lie in the fact that Borg later issued a 45EDII with similar

specs and that is reportedly an excellent optic, good for powers over 100x

(which mine was not).

Borg 50ED

Image

Credit: Cuzic Mihai, with thanks.

|

Lens Design |

ED doublet |

|

Aperture |

50mm |

|

Focal Length |

500mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F10 |

|

Length |

N/A (varies) |

|

Tube diameter |

54mm |

|

Weight |

~150g |

The 50ED is - just maybe – the most specialised Borg objective in this series and one I only became aware of recently, thanks to a reader. Extreme because this is a 50mm that operates at F10! Given that the Mini 50 is quite well corrected as an F5 achromat, you could expect that the 50 ED would offer supreme correction and it does. But why though?

The answer is image scale. If you want to image the Moon (or Sun, with a filter), or specifically an eclipse, then most of the objectives here just won’t generate enough image scale on a typical sensor, whereas at 500mm the Moon will cover enough pixels for a usable cropped image. What’s more, the field will naturally be flatter than at faster focal lengths.

For the few visual astronomers left out there, I’m told it also makes for super-sharp high-power views without having to buy a Nagler 2-4mm zoom eyepiece (if you can find one).

Interestingly, this is one of the few (only?) Mini 50 objectives I’ve seen with the writing around the lens like larger Borg objectives (or a Takahashi)!

The downside is that you’ll need to raid the Borg parts bin for extension tube(s) to bring it to focus on the Mini Borg drawtube. Still, I’d actually like one of these.

Borg 50FL

Borg

objectives are shipped in cubes (sorry)!

|

Lens Design |

Fluorite (front

surface) doublet |

|

Aperture |

50mm |

|

Focal Length |

400mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F8 |

|

Length |

N/A (varies) |

|

Tube diameter |

54mm |

|

Weight |

140g |

The 50FL was a crazily expensive lens for a mere 50mm, intended to provide truly uncompromised performance at F8 and made by Canon/Optron like a Takahashi.

50mm F8 is the same basic spec’ as a Takahshi FC-50, but actually it’s not the same design. Both do employ fluorite for the positive element, but in the FC-50 it’s at the back and spaced by foil. The Borg lens is more sophisticated – the fluorite is at the front and there’s an air gap between it and the negative element for better correction (theoretically).

The 50FL makes an impressive visual planetary scope for the aperture – easily taking 100x and more – but also has a niche as a miniature eclipse imager.

It was often sold in a Mini Borg tube with Borg’s tiny M57 Crayford focuser – a very attractive and likely functional OTA with more focus travel than one of Borg’s helicals.

Borg Mini 54 Achromat

Stock image.

|

Lens Design |

Doublet

achromat |

|

Aperture |

54mm |

|

Focal Length |

300mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F5.6 |

|

Length |

N/A (varies) |

|

Tube diameter |

N/A (varies) |

|

Weight |

139g objective

only |

This is Borg’s latest small achromat – an entry-level lens to get people assimilated into the Borg. Problem is, it’s just not the cheap option that the original Mini 50 was. It’s also a longer focal length than the original at 300mm, F5.6 and so may not focus in the original tube without an extension.

Based on my experience with the Mini 50, I would expect a very useful optic for visual astronomy.

Borg 55FL

Stock image.

|

Lens Design |

Fluorite (front

surface) doublet |

|

Aperture |

55mm |

|

Focal Length |

250mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F4.5 |

|

Length |

N/A (varies) |

|

Tube diameter |

N/A (varies) |

|

Weight |

205g objective

only |

This is Borg’s current smallest fluorite lens cell from Canon and so it’s predictably not cheap, but at perhaps half the price of the 72FL, almost a bargain by Borg standards! Like the 67FL before it, the 55FL operates at a very fast F4.5 (250mm focal length). But in this case the smaller aperture means excellent correction for chromatic aberration.

The dedicated DGQ55 0.8x reducer takes the 55FL down to 200mm/F3.6 in an OTA that’s not much larger or heavier than a regular 200mm prime but delivers outstanding correction and good coverage at full frame.

I suspect that the 55FL is aimed at the wild bird imaging market in Japan, but it also offers fast, wide field imaging for those wanting to capture Barnard’s Loop, for example.

Of course, for the plump of wallet, the 55FL is also going to be a super-luxury mini travel and wide-field scope that weighs less than a kilo all-in.

For such visual use, the 55FL is sold packaged with the short M57 black drawtube assembly, part 6011; but for astro’ use you could get away with just one of the M57 helical focusers (parts 7761 or 7758) and 80mm worth of extensions for the main tube – those focusers have enough travel without the drawtube.

The 55FL seems an obvious upgrade to the original Mini Borg OTA (see above) but for visual with a 1.25” diagonal, the 55FL has an extra 45mm of light path in the flared adapter behind the objective, so there’s not enough in-focus (i.e. the Mini Borg drawtube is too long).

For mounting, Borg sell a version of the drawtube with an Arca dovetail, but a better solution is just to use a 60mm tube ring (from Borg, More Blue or others) so you can easily use it without mounting hardware as a telephoto.

Borg 60 Achromat

|

Lens Design |

Doublet

achromat |

|

Aperture |

60mm |

|

Focal Length |

325mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F5.4 |

|

Length |

N/A (varies) |

|

Tube diameter |

N/A (varies) |

|

Weight |

200g objective

only |

Another early move by Borg to extend the usefulness of the Mini Borg concept, it looks much like the ED but offers a much cheaper (back in the day it had a Japanese list price of around Y17,000 – about $130) upgrade but without the ED element.

In the Mini Borg tube it was seriously small and light as usual – less than 500g ready to go.

Borg themselves suggested it was ‘ideal for nebulae and star clusters’. To me that means it probably has too much false colour for higher magnifications (and too much violet bloat for imagers).

Borg 60 ED

|

Lens Design |

ED doublet |

|

Aperture |

60mm |

|

Focal Length |

350mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F5.8 |

|

Length |

N/A (varies) |

|

Tube diameter |

N/A (varies) |

|

Weight |

210g objective

unit only |

The 60 ED was an interesting early addition to the Mini Borg system. Shipped with an adapter (amusingly called a ‘trumpet’ or ‘cornet’ in Google’s translation), it threads onto the Mini Borg drawtube and come to focus without extensions, providing a tiny and light scope with much more astronomy potential than the Mini 50, yet adding just ~150g extra (the 60ED objective weighs 210g).

The 60ED is a 350mm/F5.8 Steinheil (!) doublet with an ED rear element and a larger-than-foil air gap.

That’s a similar spec’ to a TV-60 and you’d expect similarly good correction for false colour, but in an even lighter tube (at perhaps 500g all-in) and with the option of a 2” visual back. However, it seems to have significantly worse false colour than the TV-60, possibly due to a cheaper ED glass, a smaller air gap or both.

Borg 67FL

Borg 67FL

and Takahashi FS-60C.

|

Lens Design |

Fluorite

doublet |

|

Aperture |

67mm |

|

Focal Length |

300mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F4.5 |

|

Length |

270mm |

|

Tube diameter |

80mm or 54mm |

|

Weight |

880g OTA as

shown |

Even by Borg standards, the 67FL was a bit wild. In what way? Because it’s F4.5 (300mm) – a truly extreme f ratio for a simple doublet. With a reducer this puts it into fast camera lens territory but with much higher optical quality: a miniature 300mm telephoto of the highest fidelity for terrestrial photography or imaging.

For visual astronomy I expected a mess, but not so. The 67FL proved excellent, much the same as a Takahashi FS-60, but with more aperture and in a much smaller OTA. Yes, it has some false colour, but nothing that’s generally troublesome visually and no more than many slower ED doublets.

How did Canon accomplish this?

The 67 FL uses front-surface fluorite and a significant air gap to achieve good correction at F4.5 – it’s a more sophisticated design than the FS-60. Perhaps it was expensive to produce and that’s why this seems to be a rare lens.

In true Borg style it’s small and very light – about 880g as you see it above in a series 80 OTA. The objective was supplied with an adapter to fit the Mini Borg system too, so potentially even lighter is possible.

Swift Model 838

|

Lens Design |

Fraunhofer

achromat |

|

Aperture |

50mm |

|

Focal Length |

700mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F14 |

|

Length |

700mm |

|

Tube diameter |

50mm |

|

Weight |

~6 Kg incl.

mount |

On the face of it, the Swift Model 838 is just like zillions of other small long-focal-length achromats sold mainly for kids and teens in the space-obsessed 1960s. So just like a Tasco then? Really, not.

You see many believe that Swifts from that era are basically proto-Takahashis. Certainly everything from optical quality to mechanical finesse and the style of the fittings is reminiscent of a Takahashi. However, though the basic optical specs are the same as Takahashi’s TS-50 (see below), everything else is different in detail.

The Model 838’s 50mm F14 foil-spaced Fraunhofer achromatic objective may not sound much, but it is effectively perfect and so surprisingly capable. I’ve seen no other kid’s scopes from this era with such fine optics, certainly not a Unitron and not even the Carton I reviewed.

The Model 838 had a beautifully made and very smooth cast focuser in Swift-signature coffee enamel that helps make the most of the objective. Amazingly, that focuser has a serial-number plate too.

The elegant wooden case contains various accessories – eyepieces, prism diagonal, barlow - as usual for this type of scope; but unlike most, these accessories are beautifully made like the scope.

The little push-pull equatorial has no slo-mo controls but is steady and solid and again very finely engineered (though, it must be said, quite different from the TS-50’s).

The OEM eyepieces performed quite well (though their conical steel tops make for painful eye poking in the dark). But with a few multi-coated Takahashi Ortho’s, the little Swift gave superb views of the pre-Apollo Moon which would likely have been its main target in a 1960s back yard or garden, of Jupiter and Saturn too. The Swift’s manual optimistically suggested looking for Lake Sirutis on Mars, but I at least thought I saw a polar cap.

If the Swift Model 838 really is a kissing cousin of the Takahashi TS-50, it’s a bargain at current prices. Even if it isn’t, the little Swift is a very special little telescope if you’re looking for a space-race era nostalgia piece of real quality.

Takahashi TS-50

|

Lens Design |

Fraunhofer

doublet |

|

Aperture |

50mm |

|

Focal Length |

700mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F8 |

|

Length |

~700mm |

|

Tube diameter |

51mm? |

|

Weight |

1.7 Kg OTA

(+5.5 Kg mount) |

Takahashi’s TS-50 first appeared on their website history page in a brochure from 1971, but it may have been produced even earlier - information seems scarce.

Like the Swift 838 (above), The TS-50’s 50mm F14 foil-spaced Fraunhofer achromatic objective sounds basic, but is likely of superlative optical quality. In this case, that lens sits in a proper cell that looks just like any other Takahashi’s, complete with push-pull adjustment screws for collimation. Even the coatings look unusually dark for the time.

The rest of the iconic Takahashi style was pretty much complete fifty years ago. The TS-50 has the usual cast silver focuser knobs, the same familiar tube style, the same focuser and dew-shield pattern as later models like the FC-65. The finder appears to be the same 5x25 unit you see on the FC-50 and FC-60 below. Even the mount looks similar to later ‘Space Boy’ models and the P2Z.

Finding all that nostalgia-inducing Takahashi engineering and style in what is essentially a 1960s kid’s starter scope is maybe why the TS-50 isn’t cheap today (and in fact the original marketing flyer shows a base price of 28,000 Yen – hardly cheap in 1971).

Original accessories included 12.5mm and 25mm Kellner eyepieces and a prism diagonal (that does look just like Swift’s), all in a lovely wooden box typical of the time (even my 1970s Tasco 3” had one).

Takahashi FC-50

|

Lens Design |

Fluorite

doublet |

|

Aperture |

50mm |

|

Focal Length |

400mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F8 |

|

Length |

~350mm w/o

visual back |

|

Tube diameter |

68mm |

|

Weight |

~1.2 Kg |

The

FC-50 is mini-madness: a perfect F8 fluorite doublet in a proper Takahashi

tube, with a proper Tak’ focuser and finder for the price of a decent

imaging rig. And whilst that price reflects rarity value now, in truth it was

always ridiculously expensive.

The

FC-50 looks like a cut-down FC-60 and shares its focuser and 68mm tube, but

there are differences. The FC-60 has plastic knobs; the FC-50 miniature

versions of the cast ones from big Tak’s. The FC-60 has a fixed cell, the

one on the FC-50 is collimatable. It’s as if

they occupy different marketing niches: the FC-60 a working scope, the FC-50 a

miniature for the wealthy owner of an FC-125.

In

fact, the FC-50 was introduced with a range of F8 fluorite doublets in the

early 1980s, long before the similar FC-60, which may explain those

differences.

All

the original FC-series were signature Tak’ doublets with

fluorite-at-the-back Steinheil lenses optimised for planetary, lunar and solar

viewing (the FC-50 was available as part of a solar kit and such scopes lack

the usual green lens engraving).

For

Solar System objects, performance is remarkable because the little F8 doublet

has almost perfect correction. Consequently, planetary and lunar views are

remarkable for the aperture: the FC-50 shows Martian albedo markings like

Syrtis Major better than an FS-60 or TV-60, for example.

The

FC-50 came with a 0.965” visual back and a matching prism diagonal,

perhaps a couple of Takahashi MC Ortho eyepieces. But to get the most out of it

you’d need the 4mm and even 2.8mm Hi-Orthos.

Alternatively, just swap the visual back for a modern 1.25”.

The

FC-50 was marketed on Tak’s smaller equatorials like the Teegul and Space

Boy, but can also be found on a table mount specifically designed for it (the

‘FC-50 Theodolite’ – see above).

The

FC-50 is rare now – expect to have to hunt and wait, then pay the

seller’s asking price fast when you find one.

Takahashi FC-60

|

Lens Design |

Fluorite

doublet |

|

Aperture |

60mm |

|

Focal Length |

500mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F8.3 |

|

Length |

420mm w/o

visual back |

|

Tube diameter |

68mm |

|

Weight |

1.5 Kg incl.

clamshell |

The

FC-60 was the smallest workaday scope from Takahashi’s 1980s FC range of

F8 fluorite-at-the-back Steinheil doublets, optimised for planetary and lunar

viewing and imaging. It shares a 68mm tube and tiny focuser with both the FC-50

and modern FOA-60.

If

you want a small scope for travel or quick looks at the Moon and planets, it

still has advantages today, even though it was discontinued more than two

decades ago. The FC-60 is lighter than Tak’s recent planetary 60mm

scopes, the FS-60Q and FOA-60, better corrected than the former and likely more

rugged than the latter (see below).

For

the Solar System, the FC-60 outperforms F6 doublets like the TV-60, FS-60 and

small Chinese doublets with similar specs. Why? Because its F8 lens is properly

corrected into the red for Mars, gives colour-fringe-free views of Venus and

will take higher powers generally. But for deep sky (visual and imaging) its

uncoated fluorite element is a (minor) disadvantage.

Despite

its length, the FC-60 mounts fine on a photo tripod/head and the standard

clamshell has a ¼-20” thread for that reason.

The

FC-60 is easier to obtain than the FC-50, but not much.

Takahashi FS-60C/CB

|

Lens Design |

Fluorite

doublet |

|

Aperture |

60mm |

|

Focal Length |

355mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F5.9 |

|

Length |

290mm w/o

visual back |

|

Tube diameter |

80mm |

|

Weight |

1.5 Kg incl.

clamshell |

The

FS-60 was the smallest of the FS series of fluorite-up-front doublets and the

only one to survive. Unlike the others, unlike the FC-60 too, it’s an

F5.9 (vs F8) for maximum portability and wide-field imaging. It comes in two

formats – the FS-60CB variant has a shorter tube with more in-focus for

imagers.

If

some of the scopes here are deliciously rare, the FS-60 is a commoner:

Tak’ have sold freighters (well crates anyway) full and for a reason.

That reason is flexibility.

The

FS-60 can be configured a host of different ways for different purposes. In

basic form with a 1.25” visual back it’s a compact, rugged travel

scope, for astronomy but birding and nature viewing too.

With

an optional 2” visual back and a cheap flattener or more expensive

reducer, it offers a huge field for astro-imaging or as a 300-350mm terrestrial

telephoto.

Plug

in the optional CQ 1.7 module and it becomes the FS-60Q (see below) - a

flat-field telephoto lens with more image scale for eclipses, or a travel scope

for planetary/lunar viewing and a Scope Views best buy.

Unthread

the 60mm objective and thread on the FC-76D objective unit and it becomes a

different scope altogether; add the Q module into the mix and its different

again.

For

mounting, Tak’ make a regular 80mm clamshell, or a dedicated slim one

with a plate to change the balance point for use with a heavy camera. The FS-60

goes on just about any photo tripod with the built-in ¼-20” thread

on the clamshell base. You can get a Tak’ or a 3rd party

Vixen-compatible dovetail to fit the clamshell’s 35mm spaced M6 holes.

Other 80mm rings – like Borg’s which weigh under 200g the pair

– are an alternative.

Considering

it’s all Japanese made, including the Optron fluorite lens, the FS-60 is

remarkably good value. Does it have any negatives? A few.

That

Optron objective has a simple design and offers similar correction to some ED

doublets, i.e. it’s not a perfect apochromat. The focuser has a short

body and can suffer wear and slop if subjected to a heavy imaging rig. That

80mm tube means it’s chunkier (and heavier) than, say, a Mini Borg 60ED -

as heavy as an FC-60.

Still,

the FS-60 is an all-time do-everything favourite. Its long product life is

testimony to how useful we’ve all found it.

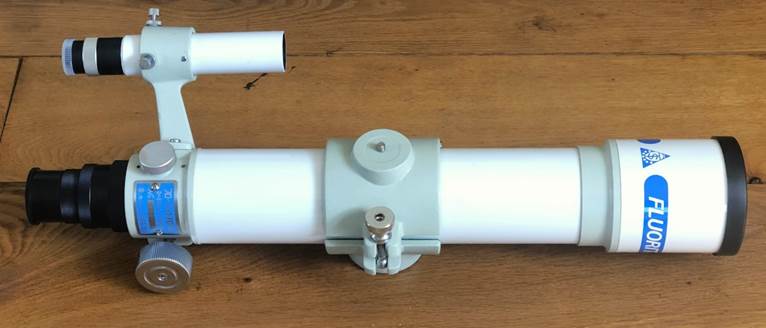

Takahashi FS-60Q

|

Lens Design |

Fluorite

quadruplet |

|

Aperture |

60mm |

|

Focal Length |

600mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F10 |

|

Length |

450mm w/o

visual back |

|

Tube diameter |

80mm |

|

Weight |

1.8 Kg |

This

was a strange departure for Tak’, but a good ’un as it turned out.

Unthread the focuser on an FS-60 and screw in a short

section of OTA with a doublet extender lens built in and you have a whole new

telescope with a focal ratio of F10, a very flat field across a full-frame

sensor, sharpened spot sizes across the field and reduced chromatic aberrations

(false colour and spherochromatism).

Despite

the module insert, the FS-60Q is still very small and light too.

This

makes the ‘Q’ a superb solution for imaging eclipses, but also

turns the slightly-compromised FS-60 into a great visual scope for the Moon and

planets.

Did

I mention it takes great terrestrial photos?

If

you buy the FS-60Q as a unit you save a bit on the price, keep the flexibility

(just remove the Q module for an FS-60) and get a special red serial plate.

Otherwise, it’s all as the basic FS-60 – small, light, rugged and

easy to mount.

For

further flexibility, plug in a reducer or swap an FC-76 objective onto the

focuser.

The

FS-60Q is among my favourite in this guide and a Scope Views best buy.

Takahashi FOA-60

|

Lens Design |

Fluorite

doublet |

|

Aperture |

60mm |

|

Focal Length |

530mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F8.8 |

|

Length |

510mm dewshield

retracted |

|

Tube diameter |

68mm |

|

Weight |

1.8 Kg |

What’s the best corrected production refractor of all time? Very possibly the FOA-60Q. But before we go there, let’s talk about the basic FOA-60.

When Takahashi discontinued the original FC line of Steinheil fluorite doublets in the early 1990s in favour of the FS series, the smallest FC-60 stayed in production for almost another decade. Its replacement was the FS-60 – a great basis for an imaging system, but not ideal for solar system viewing, especially on Mars.

Takahashi’s (eventual) answer is the FOA-60, a more specialist planetary scope even than the FC-60.

In case you wondering, ‘FOA’ stands for ‘fluorite ortho-apochromat’ because the FOA-60 is designed with similarly perfect correction to the larger TOA triplets. Instead of a triplet, the FOA-60 uses a front-surface fluorite doublet, but with a large air gap and a special dispersion mating element; if that wasn’t enough, it operates at a slow F8.8. The lenses are probably spec’d to a very high Strehl too.

That special lens is then fitted into a 68mm tube with a similar tiny focuser to the FC-60, but with a sliding dewshield and cast focuser knobs – this is a premium scope at a premium price.

But does it work? Yes! The FOA-60 is almost perfectly corrected for chromatic aberration and gives the best high-power views you could expect from just 60mm. The only slight issue is sensitivity to miss-collimation (or more likely centring) common in lenses with a big air gap, so the FOA-60 may not be an ideal travel scope.

Takahashi FOA-60Q

|

Lens Design |

Fluorite

quadruplet |

|

Aperture |

60mm |

|

Focal Length |

900mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F15 |

|

Length |

540mm dewshield

retracted |

|

Tube diameter |

68mm |

|

Weight |

~2.4 Kg incl.

clamshell |

The FOA-60Q uses the same principle as the FS-60Q: unthread the focuser and insert a special ‘Q’ module extender (not the same one). The result is an F15 super-apochromat with a very flat field across a full-frame sensor and simply no detectable visual false colour, even focusing through Venus at 200x. This is plain odd. Look through it and the FOA-60Q is indistinguishable from a reflector for false colour.

Given that the FOA-60Q is both large and very expensive for a 60mm you might very well ask (as I did), what’s the point?

In fact the FOA-60Q has some real niche uses beyond best-of-the-best bragging rights. It produces the best images of the Moon (and so eclipses) of any scope I’ve tried at anything like this aperture and will take ridiculous magnification for a 60mm.

Surprisingly, though, the FOA-60Q’s super-power may be terrestrial photography. It is the most aberration-free telephoto lens I’ve ever encountered and seriously capable (if slow) at 900mm. If I was going to make a living photographing launches, for example, I’d seriously consider one at a fraction of the cost of a Canon L lens of similar focal length.

And is it me? This is a beautiful telescope – the way telescopes are supposed to look.

But for most uses, the smaller, cheaper, lighter and less

delicate FS-60Q is all you really need.

Takahashi FC-65

|

Lens Design |

Fluorite

doublet |

|

Aperture |

65mm |

|

Focal Length |

500mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F 7.7 |

|

Length |

~450mm |

|

Tube diameter |

68mm |

|

Weight |

2.1 Kg |

The FC-65 was Takahashi’s small-scope in the 1980s. Its design is a bridge between the earlier TS-65 and later FC-60. It has a fluorite-at-the-back Steinheil doublet in a fixed-collimation cell that shares the 500mm focal length of the later FC-60 for a slightly faster focal ratio of F7.7.

A reducer was available for the FC-65 that dropped the focal ratio to F5.9 (380mm) for what back then was astrophotography (with a film camera!) not imaging.

The tube is the same length as the FC-60 and has the same 68mm diameter. Different is the dew-shield, which is larger. Also different is the focuser, which has a longer body and wider drawtube more suited to imaging (the FC-60NZ imaging version has an FC-65 derived focuser). The FC-65 focuser doesn’t have a finder mount – instead the finder mounts on a ring.

The finish on the FC-65 cast parts was always (as far as I know) the glossy blue-grey enamel that preceded the more familiar lime green. The FC-65 had proper cast focuser wheels not the cheapo plastic ones on the FC-60.

I absolutely love the classic-Tak style of the FC-65, but

there’s a problem. Without full multi-coatings the mating element suffers

from hazing in almost all these scopes. The reason is that Takahashi likely used a flint of

the KzFS group – a ‘Special Short

Flint’ – some of which, such as KZFS4, are sensitive to hazing in

contact with water vapour (poor ‘climatic resistance’ in

Schott’s terminology – KZFS4 is 3.0 on a scale of 1 to 4, where 1

is good and 4 is bad).

As a buyer this creates problems: the lens can be re-polished, but it

needs to be done by a highly skilled optician. Caveat emptor!

Takahashi FCT-65D

Stock image.

|

Lens Design |

Fluorite triplet |

|

Aperture |

65mm |

|

Focal Length |

400mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F6.2 (F4.0

w/reducer) |

|

Length |

403mm (probably

including the visual back components) |

|

Tube diameter |

95mm/80mm |

|

Weight |

1.9 Kg plus

ring |

Instead of just re-issue the original FCT-65 (one of the rarest classic Takahashis), they’ve re-imagined it for the digital imaging era, with the ‘D’ suffix found on the rebooted FC-100D and FC-76D.

The FCT-65D is one of three “new” imaging refractors from Tak’, but the only one with a new objective lens. All three are basically a small objective tacked onto the backend of an FC-100DF (or Sky-90 if you’re old enough to know what that is). But why though?

The answer lies with the compact focuser used on most small Takahashis, including the FC-76DC, the FS-60 and the FC-100DC. It’s a great unit for visual use and makes for an ultra-light OTA, but it doesn’t like heavy cameras and can develop slop. The larger Sky-90 derived unit from the FC-100DF is better, but needs a 95mm tube to attach, hence the weird look of all three scopes.

The other two new scopes in this series are variants of existing fluorite doublets – the FS-60 and FC76. Meanwhile, the FCT-65D is a fluorite triplet, like the original. But whereas the original was a very fast F4.6/300mm, the FCT-65D is a much more ‘normal’ F6.2/400mm.

Also conventional is the design of the objective. Like Takahashi’s TSA models, it’s a simple triplet with a small airspace and a central fluorite crown element sandwiched between two flints.

Unlike the FOA-60, Sky-90 and TOA models there is no large air space between the elements. This is a good thing. Why? Because large air gaps are great for correcting aberrations but are sensitive to de-centring, especially if jolted. So the FC-65 should be rugged.

Takahashi state a high central Strehl of 97.5% for an ultra-sharp image centre field. The FCT-65D is well corrected across the spectrum, too, so the FCT-65D should prove good for both imaging and visual - a triplet allows both the red and violet to be well corrected.

The FCT-65D comes bundled with a camera angle adjuster and a 2”/1.25” visual back (usually costly extras with Tak’). It will likely have a fairly flat field natively, but for more serious imaging you can choose:

1) The cheap and good 1.04x flattener with its 44mm image circle, for which you need just the CA ring 65D adapter and the L30 M55.9 extension – both inexpensive items.

2) The dedicated, fluorite-containing but unfortunately named ‘FU Reducer’. For half the price of the scope, you get F4.0/260mm at 44mm image circle.

For mounting, they sell an expensive new set of rings and plate, but I’m guessing you could just use the 95mm Takahashi clamshell which has been around for decades.

I’m excited by the FCT-65D. It’s not as innovative as the FOA-60, but should be a rugged workhorse for great images and good high-power visual too.

Tele Vue TV-60

|

Lens Design |

ED doublet |

|

Aperture |

60mm |

|

Focal Length |

360mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F6 |

|

Length |

270mm |

|

Tube diameter |

N/A - tapered |

|

Weight |

1.5 Kg |

When

Tele Vue replaced the Ranger with the TV-60, Al Nagler described it as his

‘briefcase’ scope and it is just tiny. The design is completely

different from the Ranger, with much smaller CNC tube and different optics;

only the focuser and weight-saving sliding-bar mount are the same.

The

TV-60 is a 60mm F6 ED doublet with the same specs as the fluorite Takahashi

FS-60, yet it manages to correct false colour just as well (dare I suggest

slightly better). What’s going on? The answer is that the doublet has a

biggish air gap, something that the lens designer can use to reduce aberrations

and is common in Tele Vue scopes.

The

tube is a clever piece of design, with a built-in sliding dew shield at one end

and a draw-tube with helical focuser at the other. It’s also a stealthy

satin black – a surprising advantage in less than friendly urban

environments!

The

focuser works wonderfully, but is 1.25” only. This isn’t IMO much

of a disadvantage visually (a 360mm focal length gives wide fields without

2” eyepieces), but means the TV-60 doesn’t work as a camera lens

and in fact, Televue make an I.S. version with a

different tube and focuser for that purpose.

At

just 1.5 Kg, the TV-60 will go on almost any camera tripod and works well on

TV’s own Telepod (see above). For travel, you

can buy a very useful and tiny case for it.

Vixen FL-55S

Stock image.

|

Lens Design |

Fluorite

doublet |

|

Aperture |

55mm |

|

Focal Length |

440mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F8 |

|

Length |

~380mm w/o

visual back |

|

Tube diameter |

? 55mm |

|

Weight |

~1.5 Kg |

Have

you noticed that many of the scopes in this guide are from Japan? The Japanese

seem to love quirky miniatures (me too). Along with the FC-50, the original

FL-55S was the start of this whole mini-trend.

Not

to be confused with the current FL55SS (!), but like the Takahashi FC-50, the

FL-55S was the smallest of a range of F8 fluorite doublets that Vixen marketed

in the 1990s. The range also included the FL-70, FL-80, FL-90 and FL-102. All

share large fixed-dew-shield tubes with a similar look, cast focusers and the

green hammered finish that was Vixen’s trademark back then.

The

FL-55S is very rare, perhaps because that Vixen-standard tube and focuser means

that cute it may be, but really small and portable it isn’t (certainly

not by Borg standards). The 1.25”-only visual back and visual bias (these

lenses tend not to work well for digital imaging without a flattener, due to

uneven coverage) mean it’s a very specialised scope today but one with

real appeal to fans of classic Vixens and small scopes in general (i.e. me!)

Given

that the FL-70S is exceptionally sharp and well corrected, I would expect the

FL-55S to be essentially colour-free.

The

standard rings take a standard Vixen dovetail for fitment to any small altaz or equatorial, but you would need to get creative to

adapt it for a photo head (unlike an FC-50 or FC-60).

Vixen FL55SS

Stock image.

|

Lens Design |

Fluorite

doublet |

|

Aperture |

55mm |

|

Focal Length |

300mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F5.9 native,

F4.3 w/reducer |

|

Length |

|

|

Tube diameter |

80mm |

|

Weight |

1.5 Kg |

Confusing right? Yes the name is the same, but it’s a very different scope.

The new FL55SS is a 55mm fluorite doublet operating natively at F5.9 (300mm), rather than the old model’s F8, but still made in Japan (probably by Optron).

Physically it looks nothing like the old model either, but embarrassingly like a Vixen labelled Takahashi FS-60. The main obvious physical difference with the Takahashi model is the permanently mounted dovetail plate in place of Takahashi’s ring mount – factor that in and the two are almost identical in price. Losing the clamshell should make it lighter, but in fact it’s the same weight as an FS-60 too.

Also like an FS-60, you have the choice of a flattener that increases the focal length slightly and a reducer (in this case 0.79x). These are both a bit more expensive than Takahashi’s and buying the kit with both will be almost as much as the OTA again. Still, an F4.3 200mm fluorite apochromat that covers a 44mm image circle should be impressive and images suggest it is.

Unlike the WO Red Cat (below), Vixen make a point of saying the FL55SS works really well visually too, so this isn’t just a telephoto lens.

The mounting bar is a clever solution, because it detaches to leave twin ¼-20” threads and one 3/8” thread for a photo tripod.

The big downside compared to the Takahashi is that scope’s flexibility, with the Q module or FC-76 objective unit – upgrade paths the FS55SS doesn’t have.

William Optics Red Cat 51

Stock image.

|

Lens Design |

ED quadruplet |

|

Aperture |

51mm |

|

Focal Length |

250mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F4.9 |

|

Length |

225mm |

|

Tube diameter |

80mm |

|

Weight |

1.5 Kg |

There’s no doubt the Red Cat has been having a moment: often sold out in store, they go in minutes used. The reason is that everyone now wants to image and more than anything else in this guide, the Red Cat is a camera lens.

A smaller version of the (much more expensive) Red Cat 71, the Red Cat 51 is a 51mm (!) F4.9 (250mm focal length) Petzval, with a big helical focuser and a built-in ring and dovetail - ready for imaging. It’s seriously small and light, too, at ~1.5 Kg and just 250mm long.

What’s a Petzval? A four-element refractor pioneered for astronomy by Tele Vue and later Takahashi that offers excellent correction and a wide, flat field at the expense of some vignetting. The Petzval has an ED doublet of about F10 at the front, with a half-sized reducer-flattener lens at the back. In this case, one contains FPL-53, the other FPL-51, but WO don’t say which is which; I’m guessing the expensive FPL-53 is in the (smaller) Petzval lens.

The Red Cat helical focuser is designed for imaging, with a rotator and a sensor tilt adjuster built-in (only on version 2) - features often found on much more expensive gear. It terminates in an M48 thread, so you’ll need an M48 camera adapter, not the standard M42 T-ring.

In typical WO style, the Red Cat comes in a nice soft case and includes accessories like a Bahtinov focusing mask and plate that fits Arca or Vixen style dovetails.

What’s not to like? Well, at £800 in the UK, this is an expensive 250mm telephoto and though it’s still much cheaper than something like a Borg or Vixen 55FL with a reducer, it’s less flexible too. I’d expect optical quality to be a bit lower and the Petzval design means more vignetting on larger sensors. Unlike the Borg, there’s no possibility of upgrades either.

On the (huge) plus side, there are none of those pesky Borg adapters or spacers required – the Red Cat will image straight out of the box. This is an underrated capability and means I’d consider buying one myself.

Can it be used visually? The catalogue shows a special erecting prism diagonal that needs wibbling about with an Allen key to fit – ‘nuff said, it’s a camera lens (I believe you can in fact get visual backs with 48mm threads, but whether a regular eyepiece/diagonal will come to focus I can’t say).

William Optics ZenithStar 61

|

Lens Design |

ED doublet |

|

Aperture |

61mm |

|

Focal Length |

360mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F5.9 |

|

Length |

245-315mm |

|

Tube diameter |

N/A |

|

Weight |

2.2 Kg + rings |

WO make a lot of 60-80mm scopes of slightly different specs, but the ZenithStar 61 is an example that fits in this guide.

The Zenithstar 61 has a 61mm (!) doublet objective in a very compact OTA with a quality r&p focuser with a microfocuser and scale. It is designed for imaging with the WO Flat 61 flattener, or as a mini travel scope (but its weight counts against it for that – see comments below).

Optical specs for the air-spaced FPL-53 doublet objective are much the same as a Borg 60ED, Takahashi FS-60C or TV-60, with a focal length of 360mm giving F5.9. I haven’t tried a ZS 61, but would expect its optical performance to be very similar to a Takahashi FS-60, with fluorite vs FPL-53 being a non-issue.

The ZenithStar 61 comes in a choice of red, gold, or Space Grey and gets a padded soft case as standard. Matching CNC ring and a finder dovetail are also included, as is a built-in Bahtinov mask for focusing.

The Zenithstar has a CNC mounting ring and shoe with a long Vixen-fit dovetail fitted, in matching anodising.

The ZS 61 is even more compact than the otherwise very-similar Takahashi FS-60, is about 30% cheaper and has more generous standard accessories. But the FS-60 is 30% lighter and more flexible, with more options to change its optical specs for different functions.

William Optics GuideStar 61

|

Lens Design |

ED doublet |

|

Aperture |

61mm |

|

Focal Length |

360mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F5.9 |

|

Length |

340mm |

|

Tube diameter |

N/A |

|

Weight |

1.44 Kg + rings |

The GuideStar is an interesting variant on the Zenithstar. Interesting why? Well, the GuideStar uses the familiar Zenithstar 61 FPL-53 doublet objective, but the lightweight (1.4 Kg) OTA is surprisingly Borg-like. It has an extension tube at the back for coarse focusing and a slim helical for fine focus placed just behind the objective cell.

It’s designed for use as a luxury guidescope or a small travel APO and is significantly lighter than the Zenithstar. With the WO Flat 61A flattener you can use it for imaging too.

Optical specs are much the same as a Borg 60ED, Takahashi FS-60C or TV-60: a focal length of 360mm giving F5.9.

The GuideStar comes in a choice of red, gold, or blue and gets a quality padded soft case as standard. Matching CNC rings and a finder dovetail are included, but will likely take the weight to ~2 Kg which is a bit heavier than the competition. Still, as usual for WO, the price is very reasonable for its specs.

Zeiss Jena 50/540

Stock image.

|

Lens Design |

Doublet achromat |

|

Aperture |

50mm |

|

Focal Length |

540mm |

|

Focal Ratio |

F10.8 |

|

Length |

47cm (OTA as configured) |

|

Tube diameter |

N/A |

|

Weight |

~1 Kg (excl. rings) |

Not an apochromat, but Zeiss had the idea of a high quality 2” long before anyone else.

Zeiss produced them for decades from the Fifties, but the problem for you and me is that they mostly appear as you see them – as an ‘optiksatz’ for telescope makers with a small helical focuser and two Zeiss eyepieces, all in a little box. And unlike Borg, there’s no convenient M57 thread to attach to, so making a tube assembly is a challenge (the only threads are on the front for filters!)

Still, it’s worth it because though this is just a doublet achromat, at F11 it performs outstandingly well, with super-sharp views at 100x and very modest false colour, terrestrial or astro’. Like the Telementor, the 50/540 is a lunar specialist and gave me some memorable views of the Moon’s craters.

In doing the research for my review I discovered that there are two distinct variants. The earlier ‘E’ lens is an air-spaced Fraunhofer achromat and performs a little better than the cemented ‘C’ lens. Both are beautifully fabricated in that Zeiss way.

It’s likely Zeiss did incorporate these lenses into their own OTAs, similar to the Telementor, but I’ve never seen one.

If you’re a competent ATM making a tube assembly from the Optiksatz would be a worthwhile project – the resulting scope is far from a toy and a real classic.

Summary

I

can’t possibly pick a single winner from all these similar-but-different

mini scopes.

I

really like the FC-60 for visual astronomy, because it has

good-as-you’ll-ever-need correction in a light and rugged OTA.

For

a literally pocketable astronomy scope forget the Pocket Borg and pocket an

original Mini Borg 50 if you can find one – it’s tiny, cheap and

amazingly useful.

For

the smallest visual travel scope – for general astronomy and nature

viewing – the TV-60 remains hard to beat, especially if you don’t

fancy an encounter with the Borg parts catalogue.

There’s

no question that Takahashi’s FS-60 is the most adaptable and flexible:

plug in the Q module for eclipses, the flattener or reducer for wide-field

imaging or just carry it around bare as a grab-n-go or travel scope. By the

standards of Canon-lensed scopes it’s competitively priced too.

If

you want to create the highest fidelity telephoto lens for terrestrial or wide

field imaging, then the Borg 55FL looks attractive if expensive. At a lower

price point, the Red Cat 51 is promising, but is really imaging-only. If

you’re a novice who wants to get imaging cheaply and without fuss, the WO

GuideStar is a contender.

Unlike

3” and 4” refractors, these are all limited by their aperture, but

can provide surprisingly good views or stunningly wide images in a

super-compact OTA. As the start of a do-anything system that can adapt with

your interests and needs, look no further than Takahashi’s FS-60.