How to View Mars

Mars rising over the desert at dusk

near an opposition.

Contents

Introduction

If you like lunar and planetary

astronomy, you’ll probably love trying to spot surface features on Mars

– the only planet for which that’s possible (the rest are just

clouds). It’s something I’ve been trying to do since I was about

nine.

But it’s just not as easy as it

sounds (which is part of the fun). Why?

Mars’ visible features are

mostly low-contrast differences in surface colour and brightness (albedo), or

relatively small features (ice caps and clouds). Then there’s the problem

that Mars isn’t around all that often…

Mars Oppositions

Mars only comes observably close to

Earth for a few months every two years (about every 780 Earth days), when it is

at ‘opposition’, i.e. when it is positioned on the opposite side of

Earth from the Sun and so closer. This is because Earth completes an orbit in

less time than Mars – in accordance with Kepler’s laws - and so it

‘overtakes’ Mars on the inside at 780 day intervals.

These oppositions change over longer

cycles, making some more favourable than others, because Mars has a slightly

elliptical orbit. How close it gets to Earth depends on whether Mars is at

perihelion or aphelion - the nearest or furthest nodes in its orbit – at

opposition.

Mars’ orbital plane is also

slightly tilted with respect to Earth’s, overlaying yet a third level of

cyclicity to its regular comings and goings. So how big Mars appears in the

eyepiece and how high it gets in the sky – even close to opposition

– varies. A lot.

Before space probes started to arrive

at Mars in the 1960s, this cycle of oppositions ruled professional research on

the red planet. For amateurs it still does.

What does all this mean to you? If

you want to view the Red Planet, you’ll have short windows of opportunity

and those opportunities will vary.

Here’s a table of the next five

oppositions, with Mars’ maximum angular size and the approximate altitude

it transits (when it crosses the N-S meridian and is at maximum altitude in the

sky, so best for observing) at opposition for northern Europe.

(For comparison, the best opposition

in all our lifetimes happened on August 28th 2003 with an apparent

size of 25.1” – almost twice it’s

maximum in 2027!)

As you can see, the 2025 opposition is

the most favourable for many years to come: small but at a very observable

altitude.

|

Year |

Date |

Max size |

Transit Altitude Europe |

|

2022 |

8th December |

17.1” |

~60° |

|

2025 |

16th January |

14.6” |

~60° |

|

2027 |

19th February |

13.8” |

~51° |

|

2029 |

25th March |

14.4” |

~37° |

|

2031 |

4th May |

16.8” |

~20° |

Telescopes for Mars

Do you need a special telescope to

view Mars? In a word, no. But Mars - small, low-contrast and red - demands a

lot from a scope.

Some guidelines:

· Aperture matters less than you think:

a small telescope will resolve as much as the seeing allows most nights

o

Even

a fine 3” refractor will give good views near opposition (see example

below), but…

o

~~4”

is the minimum for detailed views in a refractor, 5” in a Maksutov,

6” for a reflector

· Optical quality is very important

– poor optics usually just show a fuzzy orange ball. Optical quality is

probably even more important in reflectors

· Reflectors and catadioptrics with

smaller central obstructions work better in all but the best seeing

· Doublet refractors are best at F7 or

over: faster doublets are often optimised for imaging and so compromised in the

red, giving a significantly less sharp view of Mars

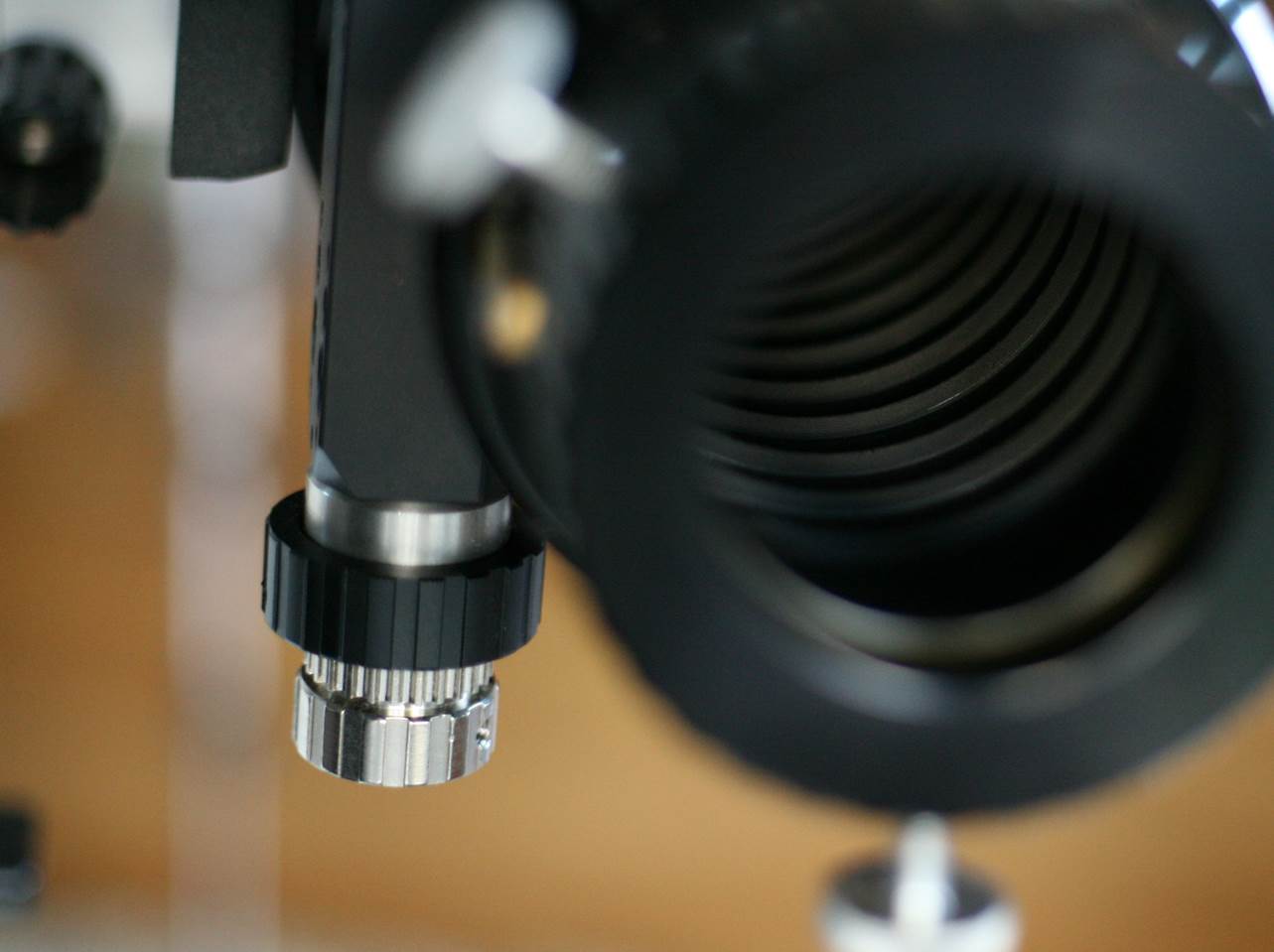

· Critical focus is vital. If your

focuser isn’t great, consider an eyepiece micro-focuser – an

accessory that slots into your diagonal

· Collimation needs to be spot-on

(usually more of a factor for reflectors)

For locations with average seeing,

I’d narrow the choice to one of the following:

· Refractor: 4 – 6” aperture:

o

Achromat

- F10+

o

Doublet

apochromat - F7+

o

Triplet

apochromat – F6+

· Newtonian reflector: 5 –

10” aperture, F8 with an obstruction of ~25% and good optical quality

· Cassegrain or Maksutov: 4 –

8” aperture, F10+ with an obstruction of ~33% or less

If you’re viewing from

somewhere with really stable seeing, then a larger aperture will show more and

other telescope types will likely work just as well (e.g. 12-16” Schmidt

Cassegrains with 35-37% obstructions).

I take a deeper dive into telescopes

for planets here.

These are just guidelines – get

out and view with whatever you’ve got. I’ve seen Mars’

classic standout feature – the arrow-head (or sometimes bikini) of Syrtis

Major – with a 50mm achromat!

This classic 80mm fluorite apochromat

on a tracking equatorial mount gives good views of Mars for a small scope.

For ED doublet refractors, longer

focal ratios are best, like this 100mm F9 Skywatcher ED Pro.

Only the best corrected triplets work

well on Mars at F6 and below: this F6 William Optics FLT-123 gives outstanding

views of Mars.

Newtonians with small secondaries,

like this 200mm F8, work well for Mars (this one gave my best ever view of Mars

with an amateur scope – at the 2003 opposition).

Orion Optics’ excellent

planetary Maksutov – the OMC140.

A stable focuser with an inner

micro-focus wheel is ideal.

Eyepieces for Mars

Eyepieces matter less than many think

- less than the telescope itself, less than the mount and much less than the

seeing. But again, some factors to consider:

· You’ll need relatively high

magnification (100x or more, even when Mars is at its largest), so eyepiece

focal lengths:

o

2.5mm

– 6mm for small refractors

o

10mm-20mm

for small to medium SCTs and Maks and Newtonians

· For telescopes with driven mounts, a

high-quality simple eyepiece like an Orthoscopic is best. Field of view matters

less than eye relief (for comfort, but also to avoid getting it greasy or

steamed-up from your eye whilst viewing)

· If you’re using a manual push-pull

mount like a Dobsonian, an eyepiece with a big flat field

is best, because otherwise the vibes will only just have settled before

it’s time to move the scope again!

· Eyepiece comfort is underrated for

seeing fine detail: the tiny eyelenses and zero eye

relief of short focal length Plössls and basic Orthos

don’t help

· Most important – keep the eye

lens clean. Baader’s Optical Wonder cleaning fluid works for me

Again, I’ve taken a deeper dive

on eyepieces for planets here.

Zeiss’ Abbe Orthoscopics are

well-regarded (if rare and expensive) planetary eyepieces.

Takahashi’s MC Orthos are another traditional choice, since replaced by

their own Abbe Orthos – cheaper than

Zeiss’!

For scopes on push-pull mounts like

Dobs, eyepieces with wide fields work best: Tele Vue’s Ethos range are

surprisingly good for planets.

Mounts for Mars

A solid, stable, preferably tracking

mount is an under-rated factor for viewing at high magnification. Keeping Mars

steady in the field of view for minutes at a time really helps you to relax,

enjoy the view and see those low-contrast features.

For alt-azimuth mounts, I prefer one

with slow-motion controls rather than simple push-pull for high magnifications

(see below).

A stable tripod can really make a

difference to the same mount. The APZ below is much more stable with a heavier

tripod intended for larger Vixen mounts than the one it came with.

In my experience, it’s

remarkable how much better the same scope seems when it is tracking and

vibe-free.

Alta-azimuth mounts work best for

high magnifications if they have slo-mo controls,

like this Vixen APZ.

Tracking equatorial mounts are best for

high powers. Scope is another planetary ‘classic’ – Takahashi’s

FC-100 with an MC Ortho eyepiece.

A mini planetary setup you can grab

and go with: Takahashi’s FOA-60 on PM-SP driven mount.

Location and Seeing

Good seeing is the most vital factor

for high power viewing and especially for those low contrast albedo markings on

Mars. Fine seeing makes a mediocre scope seem great; bad seeing a fine one

mediocre.

Dark skies aren’t important,

but a lot of ambient light can be distracting. If Mars looks like a mushy ball,

don’t give up, it’s probably not your scope. Keep trying until you

get a night of good seeing.

If travel is an option, consider

desert areas with dry and stable air and higher altitudes. Lay-bys and car

parks off roads leading to observatories are a good place to start –

pro’s choose their locations carefully for good seeing. The desert

location for the first photo is a lay-by off the ET Highway in Nevada.

Seeing matters most - almost any

scope gives great views from Mauna Kea with an average of 0.45”.

Imaging Mars

I’m not an expert planetary

imager, but the requirements for imaging Mars are a bit different from viewing.

Contrast delivery by the scope is less important because the stacking process

automatically increases contrast. The same is partly true of seeing,

because stacking helps eliminate the blur caused by atmospheric turbulence.

Meanwhile, any false colour fringing is really noticeable in stacked images.

To get the best image you’ll

want a large image scale on your chip, so smaller refractors that might give

you a good view aren’t ideal for imaging Mars. If you want to try imaging

with a smaller refractor you will need a barlow lens

to multiply the effective focal length (and so image scale).

Ideally, you need a

longer-focal-length telescope (maybe a Maksutov or SCT) with accurate tracking

to keep the image on the (small) chip of the camera, whether a specialist

planetary CCD, a consumer camera in video mode or an old webcam. Then

you’ll need stacking software to process the video stream frame by frame

and combine the best.

Fantastic results can be had by the

patient and skilled. For what’s possible, check out Damian Peach’s

images online.

A Mars Challenge

I’ve always wanted to see Nix

Olympica, the Snows of Olympus - the name given to the bright cloud cap that

sometimes cover Olympus Mons, the highest (known) volcano in the Solar System. So

far, I never definitively have done, but it’s a fun challenge to sustain

those chilly Martian vigils at the eyepiece!

Viewing Mars with one of my favourite

telescopes – Takahashi’s FS-128.

Viewing Mars with at opposition in

2022: Takahashi FSQ-85 gave surprisingly good views!