Vixen FL70S Review

Vixen made their classic 1990s apochromatic refractors - the

FL series - in a range of sizes, from 55mm to 102mm. All have fluorite doublets

at F8 or F9. All are light weight for their aperture.

The sweet spot in the FL range is arguably the FL80, a scope

I tested here and found to be excellent. But Vixen

made a couple of smaller models as well – the FL55 (not the rebooted imaging

scope) and this, the FL70.

The FL70 was the one that got me interested in the FL series.

I first saw one at a friend’s many years ago and one look was enough to tell me

it was something special. The views it gave of Venus were some of the best I’d ever had back then, with any scope.

But that was a long time ago and I was curious to see how the

FL70 stacks up today. This is a rare telescope now. People hang on to them. So to find out, I sourced a near-mint example from its

homeland for this review.

At A Glance

|

Telescope |

Vixen

FL70S |

|

Aperture |

70mm |

|

Focal

Length |

560mm |

|

Focal

Ratio |

F8 |

|

Length |

510mm

excl. visual back |

|

Weight |

2.3 Kg

incl. finder and rings/plate |

Data from Me.

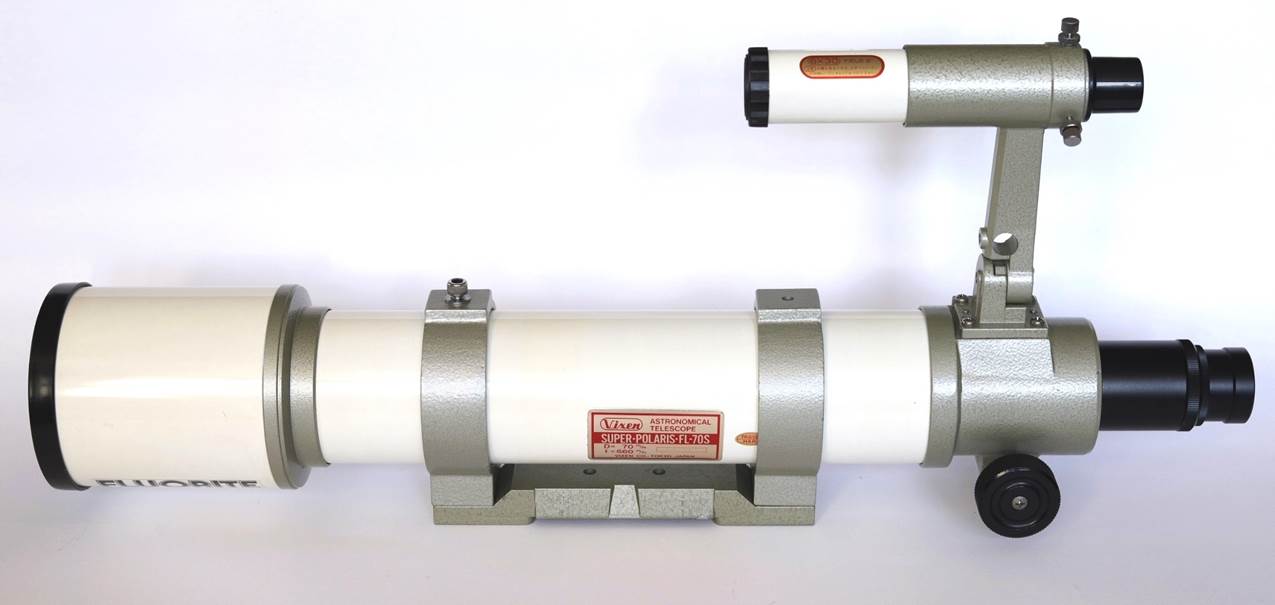

Design

and Build

All FLs have the same workaday mid-range look as Vixen

achromats from that era, less premium than a Takahashi of the time.

The focuser knobs are black plastic, as is the focuser

lock-knob; whereas on a contemporary FC-series Takahashi they are anodised

metal, or at least a classy-looking plastic imitation. The Vixen rings are

formed rather than Takahashi cast. And the tube has too many stickers for my

taste. The cast parts don’t quite exude quality like a

Takahashi somehow, either.

Though this earlier FL looks the same as later examples, it

does have some subtle differences. Whilst later FLs seem to lack a serial

number, this FL70 has one, much like a Takahashi, even if here it’s punched into a sticker, rather than a screw-on metal

plate.

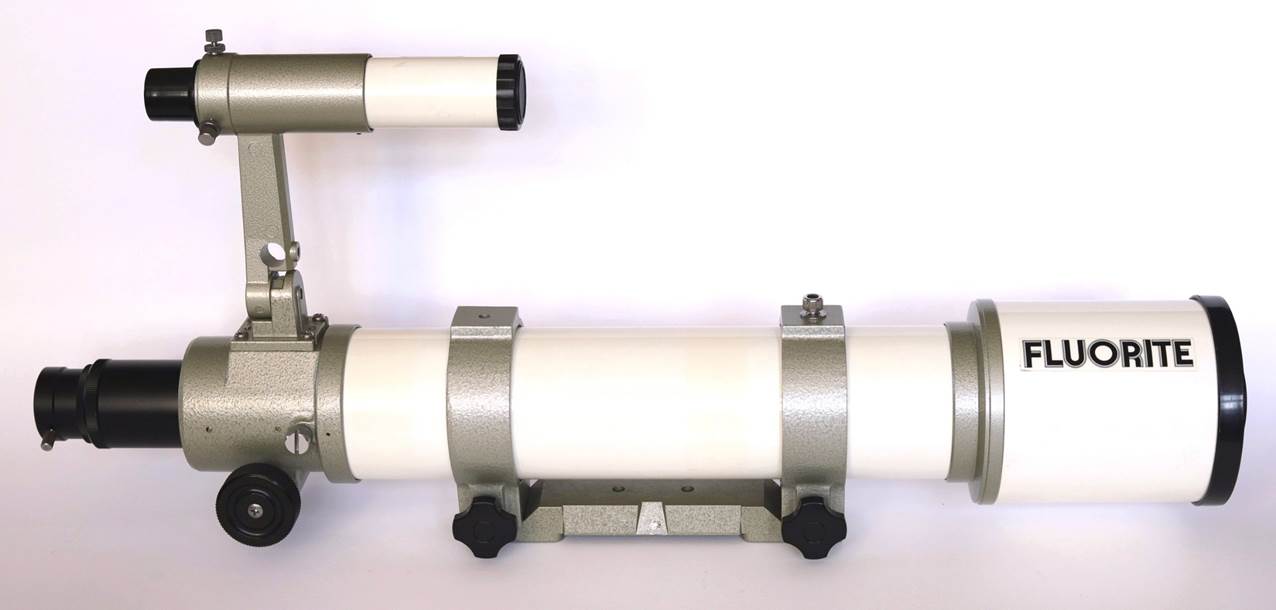

Note that some of Vixen’s FL models were re-badged with the

Orion brand (the US importer, not Orion Optics in the UK).

Note the six white dots – the lamp LEDs reflect white because

the fluorite element is uncoated.

Optics

This objective really does use the mineral, not some high-fluoride

glass like FPL-53. I confirmed this with a laser, which disappears completely

only in fluorite, not glass.

So, like a contemporary Takahashi FC60, the FL70 has a

premium F8 Japanese-made fluorite doublet lens. But note:

· Like the Takahashi FC-series (old and

new), the FL70 is a Steinheil configuration with its positive fluorite element

at the back, where it’s protected from dew and lens

cloths.

· In modern Steinheil doublets the

fluorite is coated, but the FL70’s rear fluorite element is uncoated as was the

FC-60’s. This results in lower transmissivity and a noticeably more reflective

lens (see above).

· This older FL70 has a colimatable (and probably temperature compensating) cell

like larger Takahashis of the time, complete with

engraving in yellow where a Tak’ would have had green.

But the closest contemporary Takahashi, the FC-60, has a fixed-collimation

screw-in cell, like the modern Takahashi FS-60 and the later FL80S I reviewed.

This FL70 was made back when flint glasses were doped with

lead and other heavy metals. Some leaded flints made excellent mating elements

for fluorite, but were deemed hazardous and were discontinued in favour of

‘eco’ glasses. In my experience, only a few recent high-end scopes - think Tak’s FOA-60 and FC-100DZ - have fluorite doublets with

‘eco’ (in these two cases, special dispersion) flints that match the

performance of these FL doublets.

I should mention that the FL series have legendary optical

quality. That little FL70 I saw years ago was sold to a chap who got it tested

on an interferometer; he was thrilled to find that it had a Strehl

above 99% (Tak’ fluorite doublets of the time were

made to a minimum of 95% Strehl – still excellent). Bench

tests indicate exceptionally low false colour, into super-APO territory.

Note: FLs were expensive scopes new and would be expensive to

make now – check out the prices of Optron fluorite

doublets in Taks and Borgs today.

Tube

The later

FL80S I reviewed reminded me of a big Tak’ FS-60C – a

compact tube with a short dew-shield and black-anodised fixed cell of the same

diameter. This older FL70 is classic Japanese refractor by comparison: a

large-for-the-aperture tube finished in off-white enamel, with oversized

dew-shield and a traditional lens ring in hammer-green to match the focuser. In

both cases, focuser and lens cell attach with threads. Personally, I prefer the

classic look.

The FL70S is

510mm long to the end of the focuser drawtube and 75mm diameter. Despite the

fixed dewshield, it is carry-on portable without disassembly. At just 2.3 Kg

including rings, plate and finder the FL70S is

lightweight too.

Internally, the FL70 has 3 knife edge baffles and is painted

flat black.

Focuser

The FL80S I

reviewed had a larger focuser with a 2” visual back and clever built-in rotator

suited to imaging. This one is more basic and aimed at visual use.

Note that

the fluorite scopes have thread-on focusers, whilst the similar-looking

achromats used basic set-screws.

The focuser doesn’t have the famously buttery feel of a Takahashi unit,

but it’s still a high-quality, all-metal (well apart from those knobs) item.

The feel is smooth and precise with minimal image shift.

The chromed

55mm diameter drawtube sports a thread-on visual back, three internal

knife-edge baffles and a cross-cut rack. The 80mm of travel is fine for most

eyepiece/diagonal combinations. Two internal bearings with adjustment screws

and side-mounted lock knob mean it’s stable and won’t

rack-out on its own with a heavy eyepiece.

The supplied

visual back is 1.25” only and has a set screw rather than a lock-ring. It’s the same item that came with the later FL80S. It screws

into the drawtube with an adapter on what looks like a thread about M52, so a

2” visual back might fit. A pair of thread-in extension tubes are provided for

straight-through viewing.

The 1.25”

visual back adapter has a standard thread and could be swapped out for a

different one, such as Takahashi’s twist-lock.

Mounting

This FL70 is

labelled ‘Super Polaris’ and this means it originally came on the small Vixen

equatorial of that name, a forerunner of the similar and more commonly

encountered GP mount (see below).

The FL70 is

too heavy and bulky for most photo heads (unlike, say, a smaller 70mm TV Ranger

from the same era), but works really well on a small

alt-az mount like a Vixen Porta (not the mini

version), where slightly heavier and longer scopes (even the TV-85 I was

testing at the time) struggle with excessive vibes.

If you want

a period-correct alt-az mount, then you could seek

out an old Vixen example with matching green enamel, but bear in mind that the

rings bolt-on to these mounts and don’t hinge open, so

you’ll be moving the whole setup as a unit.

For greater

flexibility I’d prefer the old ‘D’ (for dovetail)

version with (you guessed) a Vixen dovetail built-in but also weighted to

counterbalance large eyepieces.

The Vixen

Porta is later than the FL series, but works well.

Vixen FL80S on a GP mount – the later version of the SP mount

for the FL70S.

Accessories

This FL70

came with the original formed rings and Vixen dovetail plate. The rings have

the advantage of light weight, but aren’t a match for

the quality of a cast Takahashi clamshell and don’t hinge open which means

removing the focuser if you want to take the tube out!

The original

6x30 finder has quality optics (not stopped down like many cheap optical

finders) and though it has a plastic eyepiece with less eye relief than the

peerless Takahashi 6x30, field of view (8°) is the same.

The finder

mount is unusual: it allows the finder to rotate to either side, presumably to

clear the eyepiece area when used on an alt-az mount.

The

period-correct eyepieces would have been Vixen’s own Circle-V 0.965” Orthoscopics. These are of excellent quality (if not up to Tak’ or Pentax Ortho’s) and can still be had quite cheaply

if you want to assemble a full retro’ rig.

In

Use – Daytime

The size and

style of the FL70 means you probably wouldn’t use it

in a hide for nature viewing or birding, the way some do a small Tele Vue; but

daytime views are simply outstanding.

I tried using

the FL70 to view waders – Curlews and Oystercatchers - out on the bay sands

near my home. The view was almost hyper-real: sharp and vivid and completely

free of false colour in a way few spotting scopes manage. But I did get asked

by a local birder why I was using an astro’ scope!

At 100x,

silhouetted branches (my usual ‘test’) are basically free of false-colour

fringing: none in focus and the faintest (really) tint focusing through. This

is a rare result for a doublet. Sharpness meanwhile is perfect even at this

power.

It may be an astro’ scope, but the FL70 works outstandingly well for

nature viewing.

In

Use – Astrophotography

Lack of a 2”

visual back (and I couldn’t find one to buy as an

accessory) precluded deep-sky imaging, but I did take a snap of the Moon, which

is sharp and free from flare or false colour, detailed for the small image

scale.

In

Use – Observing the Night Sky

General

Observing Notes

The superb

optics are let down slightly by the focuser – it’s not

worn or sloppy or imprecise, but heavy at room temperature it gets pretty stiff

when cold and may need re-lubricating.

Cool

Down

A small

doublet in a proper cell cools fast and this is no exception – completely

usable within a few minutes and giving its best in ten to fifteen, with no

pinching or severe spherical aberration that I’ve seen

from simpler cells. This is such an important feature for a quick-look scope.

Star

Test

The star

test is effectively perfect with evenly illuminated, identical rings either

side of focus and no perceivable under or over correction. In focus at high

power yields a perfect Airy disk and dim single diffraction ring.

The

Moon

A low first quarter Moon in turbulent seeing across

the bay nonetheless shows all the major features you can see with a ~3”

refractor, including the dramatic crater grouping of Theophilus and Catharina

near the terminator.

Focusing through the bright limb at 112x reveals no

false colour fringing at all – this is a perfect Moon of only blacks, whites, greys and buffs.

I managed to see a two-day-old Moon from the top of

the fell – only a few degrees above the horizon, it’s

a difficult phase. The FL70’s peerless contrast revealed more features than I’ve ever seen in this thinnest of crescents, including Mare

Marginis and Smythii on the

very limb, dark-floored Mare Humboldtianum and spectacular

crater Gauss.

Venus

Perhaps the ultimate visual test for any refractor, a

razor-sharp crescent Venus was my first taste of the FL70’s capabilities all

those years ago.

Now, a dazzling magnitude -4.7 crescent at just 20

degrees altitude and 112x with a 5mm Nagler shows only a hint of gold on the

limb that might be atmospheric, no significant false colour focusing through

and no flare either.

Mars

The Red

Planet troubles F6 ED doublets like the TV-85 with red blur and softness. Not

the FL70. There was no blur of deep red false colour, in or out of focus; no

light bleed or flare from the limb into black space.

I

was able to view Mars near the 2022 opposition at 16.9”, near transit at 57° Altitude in fine seeing. At 140x with the 4mm setting of a Nagler Zoom, and 187x

with the 3mm in steady moments, Mars

revealed its most famous face - Syrtis Major just off centre extending into the lighter equatorial regions of Arabia to the

north. A hint of bright Hellas, with its clearly

defined arc of northern boundary, lay to the south-west. To the west, I noted the connecting strip of dark albedo – Sabaeus Sinus according to my atlas – leading to the

prominent dark area of Meridiani Sinus on the limb.

This level of detail is impressive from a 70mm.

Jupiter

A large and bright Jupiter shows its creamy hue to

perfection, with no false colour and perfect sharpness. All the main details

are on show, including the equatorial belts, polar hoods, a hint of storms and

of course the tiny disks of the Galilean moons. The maximum power I could get -

187x with the 3mm setting on a Nagler zoom - was still perfectly sharp and

contrasty.

Saturn

Again, Saturn has that buff, almost pink hue unsullied

by false colour or flare. The Cassini division is visible in the ring ‘handles’, along with the polar hood and a hint of cloud-belt banding.

It’s a perfect view at this aperture and noticeably

more feature-rich than through a 60mm apochromat of similar quality.

Deep

Sky

The superb

contrast and very tight stellar images from the high-strehl

objective make the FL70 a surprisingly good tool for visual deep sky. I had a

most enjoyable evening with it just after New Year, viewing out over the bay

from a secluded and dark spot on the Prom’.

The Great

Nebula in Orion revealed significant structure at 112x – as good as I’ve seen in a small scope. I easily picked the strange oval

misty patch of the Crab Nebula out of the darkness above Zeta Tauri too.

Open

clusters seem to be a particular strength. The Pleiades were the glitteringly

brilliant blue I’m used to in a quality refractor, but

I was surprised at the amount of nebulosity I could see, including a hint of

structure around Merope. Similarly, the Starfish in Auriga showed its sweeping

arms of stars more clearly than I recall in a scope of this aperture.

The Owl

Cluster in Cassiopea is one of my favourites, one of

the few objects that really looks its name, with ‘spooky’ (according to my

daughter) eyes and outstretched wings. The FL70 gave a wonderful view of it,

ditto the nearby Double Cluster.

Epsilon Lyrae was a perfect split in both components at 112x, but

upping the power to 187x with the 3mm setting of a Nagler zoom revealed four

perfect Airy disks with overlapping first diffraction rings and black space

between – startlingly good for a 70mm optic. I split Rigel from its dim

companion easily at 112x, even when low in the sky.

Summary

The FL70S

offers almost perfect correction in a light and compact OTA with a wonderful

classic vibe. A proper lens cell means it’s super

quick to cool – the perfect quick look scope for the Moon and planets.

Planetary and lunar views are outstanding. Terrestrial views at high power are

sharper than any spotting scope.

The only

downside is its focuser, which lacks the fluidity and absolute precision of a

Takahashi (or a modern dual-speed unit).

Most small

apochromats these days are optimised for imaging. The Vixen FL series (like Takahashis of the time) were mainly intended for visual

use, especially on the Moon and planets. What does this mean in practice?

An F8

fluorite doublet like the FL70 gives better sharpness at high magnifications

and lower in-focus false colour and spherochromatism

than a modern ED doublet built for imaging.

This was

brought home to me again when viewing Mars near opposition recently. A TV-85

gave a slightly softer view, with more unfocussed red light

bleeding into the seeing.

Finally, the

FL70’s in-between-sized aperture is unusual, but I really like it: noticeably

more capable than a 60mm, it’s still smaller than the

only modern equivalent, the Takahashi FC-76D.

Vixen fluorites like the FL70S are

getting rarer, but still make a superb alternative to a small Takahashi,

especially if lunar/planetary observing is your thing.