Vixen

VMC 95L Review

I

looked at the listing and dithered. Even at £1700 (a bargain, less-than-half

price) the year-old Questar field model was just what I wanted, but not what I

wanted to pay. I took a deep breath, closed the browser window and forgot about

it.

So

why was I looking at a super-expensive small Maksutov (that wasnít even a

proper astroí model) in the first place? The answer is the Moon.† I am collecting phases. Itís a long-term

project to get the best image I can of every day in the Lunar month. I already

have many of them, imaged from home with my 5Ē and 7Ē refractors. But

unfortunately I live in a valley with no Western horizon. So I never see early

days in a Lunation; to get them I must climb the local fell and image from its

Western slopes. I need a small, light, high-quality long focal length scope to

do the job; hence the Questar.

So if you canít afford a Questar, whatís the

next best thing?

I

wondered if the answer might be the Vixen VMC95L, a tiny, light-weight

Cassegrain with some of the Questarís convenience features like the built in

flip-mirror.

At

A Glance

|

Telescope |

Vixen VMC

95L |

|

Aperture |

95mm |

|

Focal

Length |

1050mm |

|

Focal

Ratio |

F11.1 |

|

Central

Obstruction (incl. holder/baffle) |

~36% |

|

Length |

360 mm |

|

Weight |

1.8 Kg |

Data from Vixen.

Design

and Build

The

VMC is made in China and shares its styling and design with other current

Vixens. Apparent build quality is high, with quality finish and good

mechanicals.

Open

tube and spider: the VMC 95L looks like a classical Cassegrain, but actually

itís a sub-aperture Maksutov.

Optics

The

VMC appears to be an open design like a classical Cassegrain, with a secondary

supported on a curved-vane spider (the curves reduce diffraction spikes around

stars and planets). However, itís actually a catadioptric (a combination

mirror/lens telescope like an SCT).

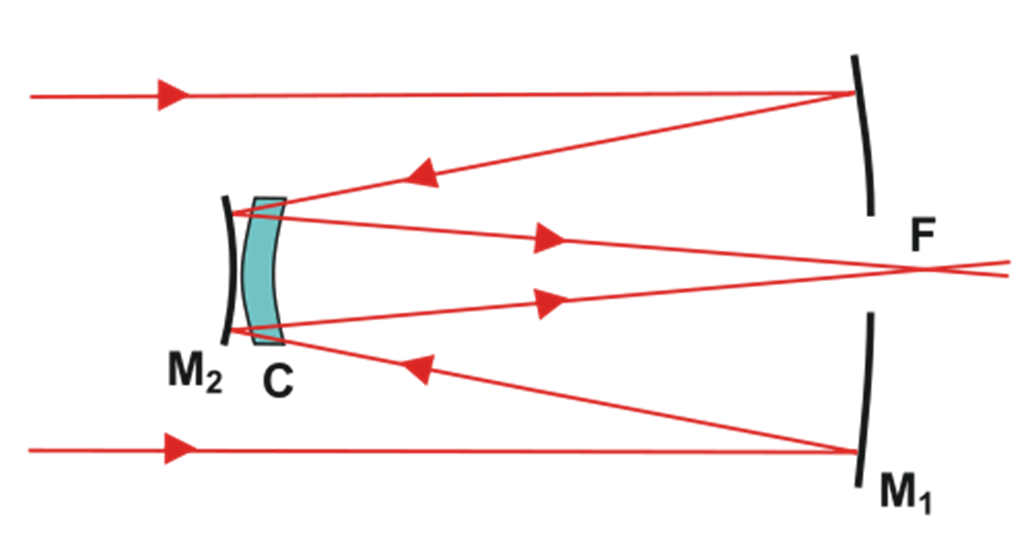

ĎVMCí

means Vixen Modified Cassegrain, but really itís a Maksutov-Cassegrain. To be

precise, itís a type called a sub-aperture Maksutov which has the thick

meniscus lens just in front of the secondary mirror, rather than across the

whole aperture:

The

advantage of the sub-aperture design is that it reduces weight and (in theory)

cool-down time, whilst providing freedom to correct for coma and field

curvature.

Disadvantages

include the need for a spider (which degrades the image a bit) and the need for

the light to go through the corrector twice, potentially increasing some

aberrations.

Sub-aperture

correctors feature in various current scopes, including some by Orion Optics

and the Tal Klevtsov, as well as a number of other Vixens.

If

the basic design is a bit unconventional, the VMC 95L is quite typical in other

ways. The focal length of 1050mm (F11.1) is short for a Maksutov, but slightly

longer than a typical F10 SCT. The central obstruction is quite large at 36%,

but no larger than most SCTsí.

If

you need to adjust collimation, itís via the main mirror only: deeply recessed

screws lie behind the oval grommets you can see in the picture. Vixen obviously

donít intend regular collimation.

Tube

The

OTA is tiny at 36 cm by 10.7 cm (14Ē x 4.2Ē) and weighs just 1.8 kg: a little

larger than a Questar, but not much.

Like

Meade with the ETX series, Vixen have tried to copy some of the features of the

Questar control box. In this case, the rear of the scope contains a flip-mirror

arrangement: an internal diagonal that can be switched out of the way to allow

imaging straight through a port on the back.

This

flip-mirror arrangement has the potential to be super-convenient for my needs:

use a wide-field eyepiece in the diagonal as a finder, then flip the lever to

the port with camera attached for imaging. As you can see, Vixen provide a

1.25Ē visual back for the port, but it threads onto a standard T-ring thread so

direct DSLR attachment is possible.

Vixen

VMC95 has built-in flip mirror.

Focuser

The

VMC has moving mirror focus, same as most SCTs and Maks. Enough focus travel is

provided to allow virtually any eyepiece or camera to come to focus in either

position. Whatís more, the focuser is fast, accurate and super-smooth with an

oversize-knob for gloved-hand convenience.

Mounting

Like

many small Chinese scopes these days (the VMC is made in China), the little

Vixen has a fixed (obviously Vixen-type) dovetail without tube rings, but you

can attach it in two positions, 90į apart to allow the VMC to be mounted

sideways on a Vixen Porta mount.

The

VMC 95L was very stable and vibration-free on my Vixen GP mount with the

smallest (~1.5 Kg) counterweight; the whole assembly was easily carried as a

unit.

The

dovetail also has a ľ-20 thread for a photo tripod (and the Little VMC 95L is

easily compact and light enough for a medium sized photo head). Tele Vueís

TelePod head was also an excellent match.

The VMC 95L is obviously highly portable, but easy

and flexible to mount too.

The

VMC95 makes for great grab-n-go portability on a GP mount.

Accessories

Unlike

a Questar, there is no built-in finder, but Vixen have provided a standard

dovetail shoe and a good RDF to fit.

In

Use Ė Daytime

I

tried terrestrial photography first and found the VMC reasonable (after an

extended cooling period), but slightly un-sharp.

Branches

(with an out-of-focus daytime Moon behind): false colour is minimal, but

sharpness poor.

In

Use Ė Astrophotography

I

bought the VMC for a specific imaging purpose, do I thought it was worth

briefly discussing use as an astrograph.

The

VMC was clearly designed for astrophotography. The design gives a wide, flat

field and the flip-mirror control-box is very useful and avoids fumbling around

exchanging eyepieces, diagonal and camera; just what I need when imaging from a

steep, windy hillside. Both ports are close to parfocal Ė another convenience.

The super-accurate long-travel focuser would also be ideal.

Feature-wise, I found the VMC ideal for

imaging.

However,

on the Moon, the VMCís intended target in my hands, I was unable to achieve

sharp images, even with careful live-view focusing. To put that in context, I

have obtained far better Lunar images with a 50mm achromatic refractor.

For

applications such as imaging of DSOs that require more modest image scale and

where absolute sharpness is less critical, the VMC might work well, but I

didnít try this.

The

Moon, imaged through the VMC, is soft and un-sharp. This was the best of many

attempts.

In

Use Ė The Night Sky

General

Observing Notes

Once

cooled the VMC 95L gave decent, but not great images.

The

VMC shows a tiny bit of CA Ė at a level similar to a short focal-length triplet

APO - but this is not an issue. It is interesting because it makes the point

that catadioptrics are not inherently completely CA-free in the way pure

reflecting designs (Newtonians and Cassegrains) are.

One

advantage of a long focal length is you only need basic eyepiece designs Ė I

used Tele Vue Plossls almost exclusively for this test.

The

focuser is very light, smooth and precise, but has some image shift and

worryingly isnít quite the same going in reverse, so having focused through the

sweet spot, you back up only to find it isnít there. One other thing about the

focuser is that it is so smooth and light that itís very easy to lose focus by

accidentally brushing against it.

If

slightly soft optics are one problem with the VMC 95L, stray light is another.

Working around a bright Moon gave very bad ghosting and reflections that flood

the view with background light, destroying contrast. A similar effect was

experienced when viewing near a street-lamp. My guess is that the secondary

needs a larger baffle. Perhaps the OTA could do with proper flocking and even a

larger primary baffle tube as well.

An

interesting comparison on one night was with a borrowed Vixen 102SS APO. The

APO is a similar aperture, but size, price and performance are all of a

different order (the APO was pin-sharp on everything, but more than twice the

size and cost of the VMC).

Cool

Down

The

first thing I noticed was how long the VMC 95 took to cool and how poor the

image whilst it was doing so, with massive astigmatism (so much so that it was

impossible to get consistent focus across the field).

In

contrast, the small APO (a TV-76) I was using alongside was usable almost

straight from a warm room. Even a borrowed Questar cooled much more benignly

and was usable before the VMC. I am not sure why this is. Perhaps the VMC has a

plate-glass mirror? Maybe the thick sub-aperture corrector just takes ages to

cool and loses alignment whilst doing so.

Star

Test

The

star test wasnít perfect, but the collimation at least looked fine.

The

Moon

The

view of the Moon was good up to about 70x, giving a bright, sharp,

high-contrast view similar to a small APO. But the image became soft at higher

magnifications Ė radically different from the Questar whose excellent optics

swallow high magnifications with ease.

Jupiter

The

image of Jupiter through the VMC was reasonable at 70x in a 15mm TV Plossl,

with multiple cloud belts visible and apparently good contrast. However, the

image again became noticeably soft at 100x using the 11mm Plossl.

Deep

Sky

The

double-double split, but not with ease I would have expected of a 95mm scope.

The

Pleiades looked good, with pin-point stars showing a fairly flat field with

well-controlled off-axis coma, as promised. The whole cluster fits easily into

the FOV of a 32mm Plossl. I noticed that the wider field conferred by the

shorter focal length was useful compared to the narrower field of the Questar.

Compact

DSOs Ė The Ring, Dumbbell, Orion Nebula etc - generally looked good in the VMC

at low-medium powers, with the large (for its size) aperture and flat field

working in its favour. In particular, M13 looked brighter and resolved more

deeply than with most small refractors.

The VMC 95L might prove a satisfying compact

deep-sky tool.

Overall in visual use I felt that the optics

of the VMC delivered just-acceptable views that didnít live up to the fine

apparent build quality and premium brand.

I bought the VMC95 to image the Moon, but it wasnít

up to the job.

Tempting to regard the VMC95 as a budget Questar;

it isnít.

Summary

In

many ways the little Vixen VM95 is a nice scope. Itís tiny, light weight and

generally well made. It sports a number of innovative features like the

flip-mirror back that are genuinely useful. Whatís more, when you finally get

it to cool down it delivers views that are acceptable (but far from excellent).

However, that brings me to the main problems:

1)

Long cool-down

time. Not only does it take ages but the scope is almost unusable meanwhile and

it spoils the VMC as a grab-and-go.† Why

the Vixen suffers from this problem Iím not sure. It could be the thick

meniscus lens in the secondary taking ages to shed heat, or it could be that

theyíve cut corners and used a plate-glass (instead of Pyrex) primary; or both.

2)

Stray light and

ghosting. The Vixen works poorly around a bright Moon (or street-lamps) due to

serious reflections, ghosting and general stray light. Again, I am not sure of

the problem. It may be that the tube needs proper flocking, or it may be in

need of a secondary baffle.

3)

Slightly soft optics.

The VMC is OK for casual visual and imaging use, but its optics arenít up to

high powers or image scales. Is this an intrinsic problem with the sub-aperture

design where the light has to go through the meniscus twice? Or is it just a

problem with mediocre optical quality in a demanding design?

In

conclusion, The VMC has enormous promise as a tiny astrograph with some clever

and convenient features, but some oversights in the design and fabrication

means it doesnít live up to that promise. It looks like a budget Questar Field

Model, but it isnít one.

Despite

some excellent features and good design, the VMC95 is not really recommended

due to soft optics, slow cool-down and stray light issues.